Radioactive decay is one of the most consistent and predictable processes in nature. Unlike chemical reactions, which can be sped up or slowed down by changes in temperature, pressure, or catalysts, radioactive decay proceeds at a fixed rate regardless of external conditions—even extreme heat. This behavior defies everyday intuition but lies at the heart of nuclear physics. To understand why heat doesn’t influence radioactive decay, we must explore the nature of atomic nuclei, the forces that bind them, and the concept of nuclear stability.

The Nature of Radioactive Decay

Radioactive decay occurs when an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by emitting radiation in the form of alpha particles, beta particles, or gamma rays. This transformation leads to the formation of a different element or a more stable isotope. The rate of decay is measured by the half-life—the time it takes for half of a sample of radioactive material to decay.

What makes this process unique is its independence from environmental factors. Whether a sample of uranium-238 is kept in liquid nitrogen at -196°C or heated to 2000°C in a furnace, its half-life remains approximately 4.5 billion years. This constancy has made radioactive isotopes invaluable in fields such as geochronology, medicine, and nuclear energy.

Why Heat Doesn’t Affect Nuclear Processes

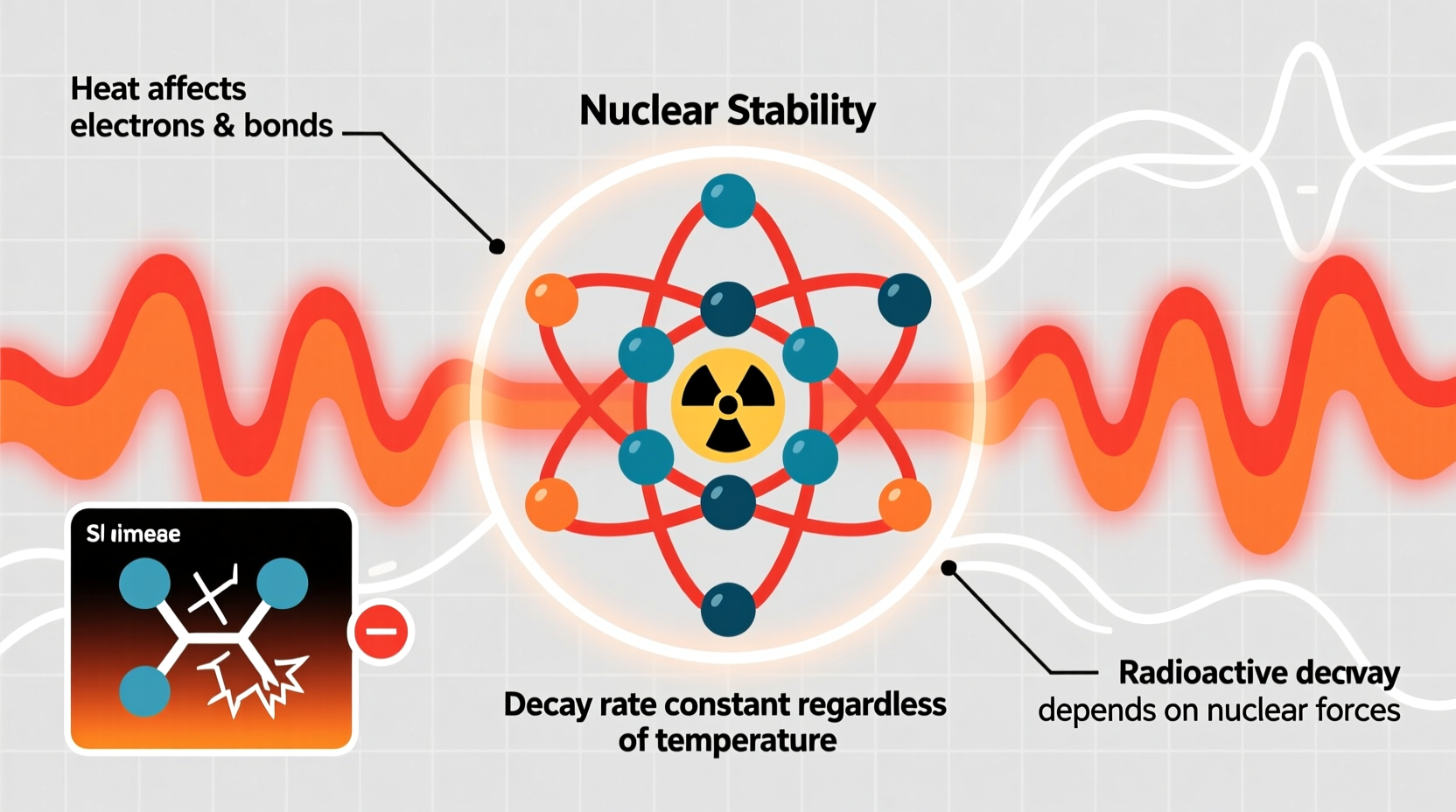

Heat affects the motion of atoms and molecules, increasing their kinetic energy and influencing electron behavior. In chemical reactions, higher temperatures mean electrons are more likely to overcome activation barriers, leading to faster reaction rates. However, radioactive decay is not a chemical process—it is a nuclear one.

The nucleus, where decay originates, is shielded from external thermal effects by the electron cloud surrounding it. The energy scales involved are vastly different: chemical reactions typically involve energies on the order of electronvolts (eV), while nuclear transitions occur in the range of millions of electronvolts (MeV). Thermal energy at even the highest achievable temperatures rarely exceeds a few eV—insufficient to influence the strong and weak nuclear forces governing decay.

“Nuclear decay is governed by internal quantum states, not by the jostling of atoms due to heat.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Nuclear Physicist, MIT

Forces Inside the Nucleus: Strong vs. Weak Interactions

The stability of an atomic nucleus depends on the balance between two fundamental forces: the strong nuclear force and the electromagnetic force. The strong force binds protons and neutrons together over extremely short distances, overcoming the repulsive electromagnetic force between positively charged protons.

However, not all nuclei achieve this balance. Those with too many or too few neutrons, or those that are simply too large (like elements beyond lead), tend to be unstable. These nuclei undergo decay via the weak nuclear force (in beta decay) or through quantum tunneling (in alpha decay), processes dictated by quantum mechanics rather than thermal agitation.

For example, in alpha decay, a helium nucleus tunnels out of a heavy atom like radium. This tunneling is a probabilistic event based on wave functions and energy barriers—not on how fast the atom is vibrating due to heat.

Key Differences Between Chemical and Nuclear Reactions

| Factor | Chemical Reactions | Nuclear Reactions (Decay) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Scale | eV range | MeV range |

| Influenced by Temperature? | Yes | No |

| Involved Particles | Electrons | Protons, Neutrons |

| Governed By | Electromagnetic Force | Strong/Weak Nuclear Forces |

| Rate Affected by Pressure/Catalysts? | Yes | No |

Experimental Evidence: Testing Decay Under Extreme Conditions

Scientists have tested whether extreme environments affect decay rates. Experiments have placed radioactive samples in high-temperature ovens, intense magnetic fields, and even inside nuclear reactors. In every case, the half-life remained unchanged within measurable precision.

One notable study conducted at Brookhaven National Laboratory monitored silicon-32 and chlorine-36 over several years under varying temperatures and pressures. No statistically significant variation in decay rate was observed. Similar results were found with cesium-137 and cobalt-60 in high-temperature plasma environments.

There have been controversial claims—such as slight seasonal variations in decay rates possibly linked to solar neutrino flux—but these remain unconfirmed and highly debated. The overwhelming consensus is that no terrestrial condition, including heat, alters the intrinsic decay probability of a nucleus.

Mini Case Study: Carbon-14 Dating in Volcanic Regions

In regions like Iceland or Hawaii, where volcanic activity exposes organic material to extreme underground heat, archaeologists still rely on carbon-14 dating with confidence. Despite being buried in geothermally active zones, once-living organisms show consistent decay patterns. A piece of wood from a 2000-year-old lava flow will exhibit exactly the expected level of carbon-14 depletion—no more, no less—regardless of the heat it endured after burial.

This reliability underscores the principle: thermal history does not reset or accelerate nuclear clocks. It’s not the environment that matters, but the moment biological activity ceased and carbon uptake stopped.

Understanding Nuclear Stability and the Valley of Stability

Nuclear stability can be visualized using the “valley of stability”—a plot of neutron number versus proton number where stable isotopes cluster. Nuclei lying outside this valley are unstable and will decay toward it.

- Nuclei with excess neutrons undergo beta-minus decay (neutron → proton + electron + antineutrino).

- Nuclei with excess protons may undergo beta-plus decay or electron capture.

- Very heavy nuclei (Z > 82) often emit alpha particles to reduce mass and charge.

The path a nucleus takes to reach stability is determined solely by its internal composition and quantum state—not by temperature, pressure, or chemical bonding. Even ionizing an atom completely (removing all electrons) has negligible effect on its decay rate, further proving the nucleus operates independently of its electronic environment.

Checklist: Factors That Do and Don’t Influence Radioactive Decay

- DO consider nuclear composition (N/Z ratio) as a key factor in decay likelihood.

- DO rely on half-life consistency for applications like radiometric dating.

- DON’T expect cooling or heating to extend or shorten decay times.

- DON’T confuse chemical stability with nuclear instability.

- DO account for quantum tunneling effects in alpha-emitting isotopes.

- DON’T assume external energy inputs can trigger or halt decay.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can anything change the rate of radioactive decay?

Under normal conditions, no. Only in extremely rare cases—such as electron capture decay in fully ionized atoms stripped of electrons—has a minor change been observed. Even then, the effect is minimal and not applicable to common decay modes like alpha or beta emission.

If heat doesn’t affect decay, why do nuclear reactors require cooling systems?

Cooling systems manage the heat generated by radioactive decay and fission reactions, not to control the decay itself. The decay continues regardless, producing thermal energy that must be removed to prevent meltdowns.

Does pressure or chemical bonding affect decay rates?

No meaningful effect has been observed. While theoretical models suggest minute influences in specific scenarios (e.g., bound-state beta decay), these are exceptions that don’t apply to everyday conditions or standard isotopes.

Conclusion: Embracing the Predictability of the Atomic Nucleus

The insensitivity of radioactive decay to heat is not a limitation—it’s a feature. This unwavering predictability allows us to date ancient rocks, treat cancer with targeted radiotherapy, and generate power in nuclear reactors. Understanding that nuclear stability arises from forces far deeper than molecular motion empowers scientists and engineers to harness these processes with precision.

Instead of trying to manipulate decay through external means, focus on safe handling, accurate measurement, and responsible application. The nucleus follows its own rules, indifferent to our attempts to rush or delay it. Respect its autonomy, and you unlock one of nature’s most reliable clocks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?