Soap has been a cornerstone of hygiene for thousands of years, yet few people understand exactly why it works so well. It’s not magic—it’s chemistry. At its core, soap’s ability to clean stems from its unique molecular structure and interaction with water, oil, and dirt. Understanding this process reveals why simply rinsing with water isn’t enough and how soap transforms cleaning into an efficient, effective act.

The Molecular Structure of Soap

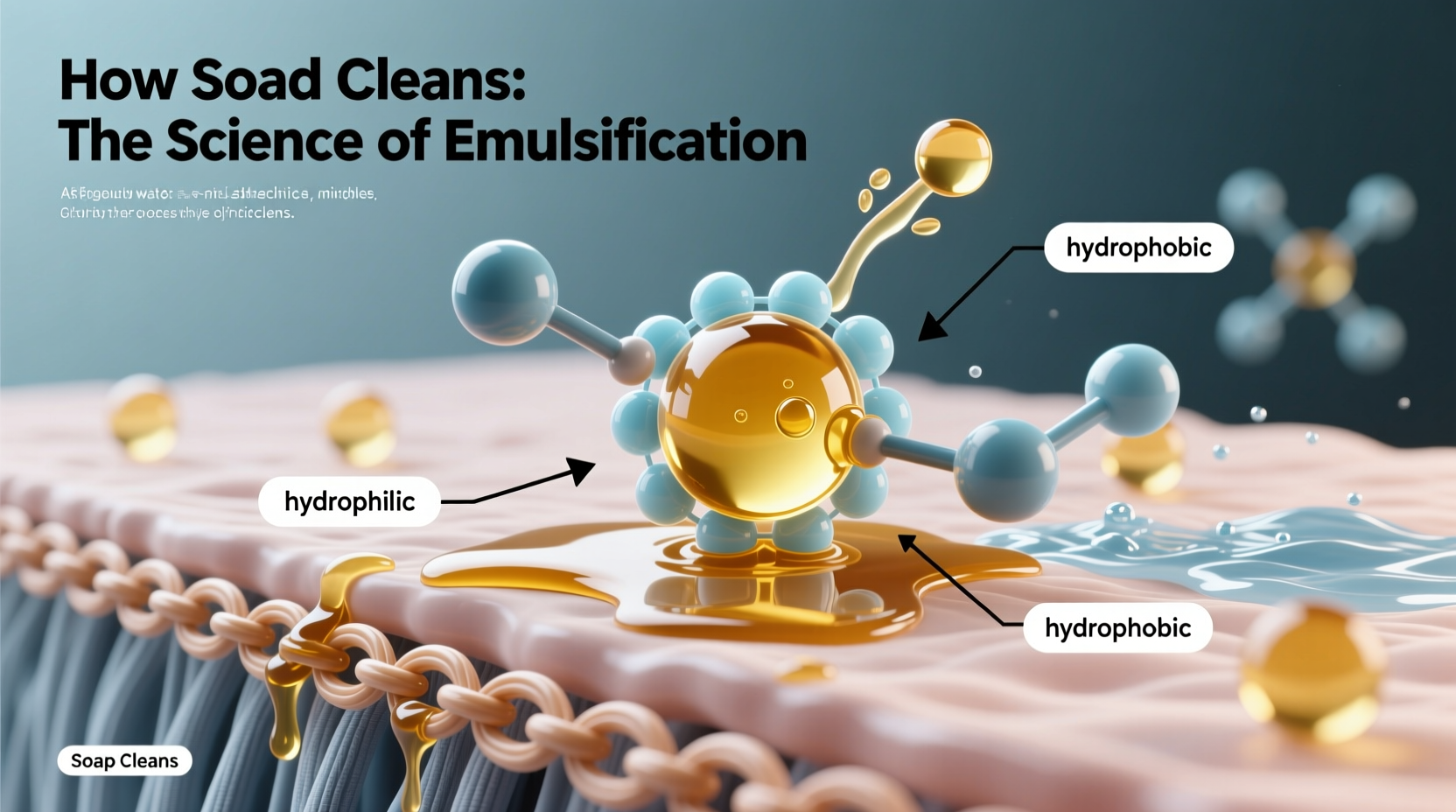

Soap is made through a chemical reaction called saponification, where fats or oils react with a strong alkali (like sodium hydroxide) to produce glycerol and fatty acid salts—what we call soap molecules. Each soap molecule has two distinct ends: a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and a hydrophobic (water-hating, oil-loving) tail.

This dual nature is key. The hydrophilic head readily bonds with water, while the hydrophobic tail avoids water and instead attaches to oils, grease, and dirt—substances that are typically non-polar and insoluble in water.

How Soap Breaks Down Dirt and Germs

When you apply soap to your hands or a surface, the hydrophobic tails embed themselves into grease, grime, and microbial membranes, while the hydrophilic heads remain oriented toward the surrounding water. As more soap molecules gather around a droplet of oil, they form spherical structures called micelles, with the oily debris trapped inside and the water-friendly heads facing outward.

These micelles are suspended in water and can be easily rinsed away, carrying the trapped dirt and microbes with them. This emulsifying action is what makes soap so much more effective than water alone.

In the case of bacteria and viruses, particularly enveloped viruses like influenza or SARS-CoV-2, soap doesn’t just remove them—it disrupts their structure. The lipid envelope surrounding these pathogens is vulnerable to the hydrophobic action of soap, which dissolves the membrane and renders the microbe inactive.

“Handwashing with soap doesn’t just wash germs away—it literally breaks them apart.” — Dr. David L. Katz, Preventive Medicine Specialist

Step-by-Step: The Science of Washing Hands with Soap

Cleaning with soap follows a logical sequence grounded in physical chemistry. Here’s what happens during a proper handwashing routine:

- Wet skin with water: Water begins to loosen surface dirt but cannot dissolve oils.

- Apply soap: Soap molecules spread across the skin, with hydrophobic tails attacking oil-based contaminants.

- Lather and scrub for 20 seconds: Mechanical friction helps dislodge debris and increases contact between soap and contaminants.

- Micelle formation: Oil, bacteria, and viruses are encapsulated in micelles and lifted from the skin.

- Rinse thoroughly: Water carries away the micelles, removing trapped impurities.

- Dry hands: Drying further reduces microbial load, as many pathogens thrive in moisture.

This entire process leverages both chemical action (soap’s molecular design) and physical action (scrubbing and rinsing). Skipping steps—especially duration or rinsing—reduces effectiveness significantly.

Types of Soaps and Their Cleaning Efficiency

Not all soaps work the same way. While traditional bar soaps and liquid soaps share the same basic mechanism, additives and formulations can influence performance.

| Type of Soap | Main Ingredients | Cleansing Strength | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bar Soap | Sodium tallowate, sodium cocoate | High | General hand and body washing |

| Liquid Hand Soap | Potassium-based surfactants, moisturizers | High | Public restrooms, frequent use |

| Antibacterial Soap | Triclosan (now largely banned), benzalkonium chloride | Moderate to High* | Medical settings (with caution) |

| Castile Soap | Olive oil-based surfactants | Moderate | Sensitive skin, eco-conscious users |

| Synthetic Detergents | Sulfates, cocamidopropyl betaine | Very High | Heavy-duty cleaning, laundry |

*Note: The CDC states that regular soap is as effective as antibacterial soap for germ removal, and overuse of antimicrobial agents may contribute to resistance.

Common Misconceptions About Soap and Cleaning

Despite widespread use, several myths persist about how soap functions:

- Hot water alone kills germs: Heat can help, but temperatures needed to kill most pathogens would burn skin. Soap’s chemical action is far more important.

- All soaps are antibacterial: Most soaps remove germs through rinsing, not killing them. True antibacterial agents are specific and regulated.

- More lather means better cleaning: Lather is mostly aesthetic. Some effective soaps produce little foam, especially if low in sulfates.

- Soap kills viruses: Technically, soap disrupts viral envelopes, inactivating them rather than “killing” (viruses aren’t alive to begin with).

Real-World Example: Outbreak Prevention in Schools

In 2017, a primary school in rural India introduced a structured handwashing program using plain soap and timed scrubbing (20 seconds). Before the program, absenteeism due to gastrointestinal illness averaged 15% monthly. After six months of education and infrastructure improvements (soap and water access), absenteeism dropped to 6%.

Health inspectors noted that the key factor wasn’t the type of soap, but consistent use and proper technique. Children learned that soap doesn’t just “cover” germs—it surrounds and removes them. This real-world case underscores that understanding how soap works leads to better habits and measurable health outcomes.

Checklist: Are You Using Soap Effectively?

To ensure you’re getting the full benefit of soap’s cleaning power, follow this checklist:

- ✅ Wet hands before applying soap

- ✅ Use enough soap to create a good lather

- ✅ Scrub all surfaces—including backs of hands, between fingers, and under nails—for at least 20 seconds

- ✅ Rinse thoroughly under running water

- ✅ Dry with a clean towel or air dryer

- ✅ Store soap in a draining dish to prevent bacterial growth on bars

- ✅ Replace liquid soap dispensers regularly to avoid contamination

Frequently Asked Questions

Does soap expire?

Most soaps remain effective for years, but their quality degrades over time. Bar soaps may dry out or grow mildew if left in water. Liquid soaps can separate or lose scent. While expired soap isn’t dangerous, its cleaning and moisturizing properties diminish.

Can I make soap remove germs without rinsing?

No. Rinsing is essential. Soap lifts germs into micelles, but those must be washed away. Wiping or air-drying won’t remove them effectively. This is why hand sanitizers (which don’t require rinsing) use alcohol to kill microbes in place.

Is natural soap better than synthetic?

Not necessarily. “Natural” doesn’t mean more effective. Some plant-based soaps are excellent, while others lack sufficient surfactants. Conversely, synthetic detergents can be highly engineered for superior cleaning. What matters most is formulation and proper use.

Conclusion: Harness the Power of Simple Science

Soap works because of a brilliant molecular design forged by chemistry and refined over centuries. Its ability to bridge water and oil allows it to lift away dirt and dismantle harmful microbes. This isn’t just useful knowledge—it’s empowering. When you understand why soap cleans, you’re more likely to use it correctly, consistently, and confidently.

Whether you're washing your hands, dishes, or clothes, remember: the real power isn’t in the brand or the scent, but in the science. Take control of your hygiene by respecting the process—lather well, scrub long, rinse thoroughly, and dry completely.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?