At first glance, spiders might seem like just another type of insect—small, many-legged, and often found crawling in gardens or corners of homes. But despite common misconceptions, spiders are not insects. They belong to a completely different class of arthropods with distinct anatomical, behavioral, and evolutionary traits. Understanding why spiders aren’t insects isn’t just a matter of scientific curiosity—it helps us appreciate biodiversity and improves pest identification, ecological awareness, and even safety when dealing with venomous species.

This article breaks down the fundamental differences between spiders and insects, from body segmentation to leg count and sensory organs. You’ll learn how scientists classify these creatures, what makes arachnids unique, and why accurate categorization matters in both biology and everyday life.

Anatomical Differences: Body Segments and Structure

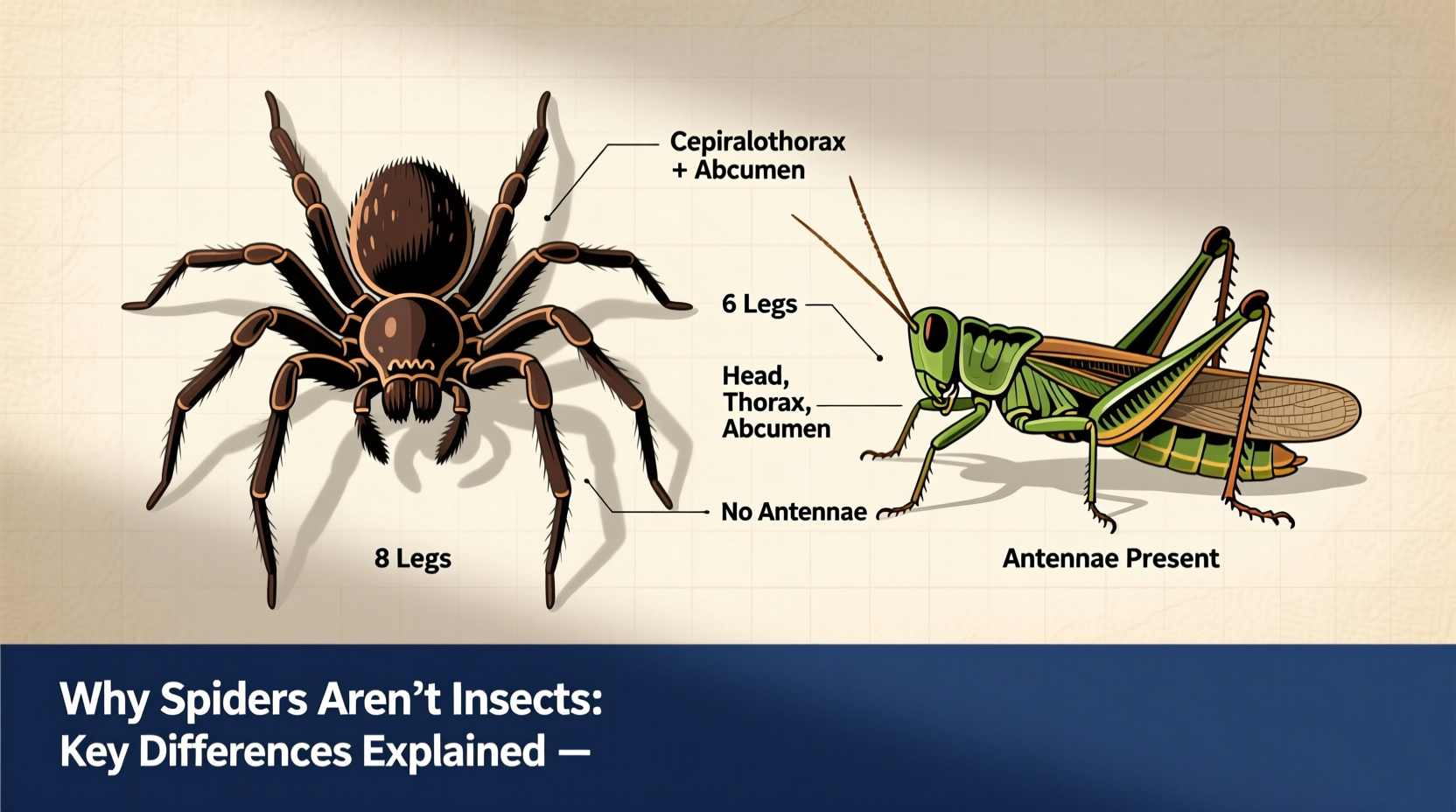

The most immediate way to distinguish spiders from insects lies in their body organization. Insects have three clearly defined body regions: the head, thorax, and abdomen. Each section serves a specific function—sensory input (head), locomotion (thorax), and digestion/reproduction (abdomen).

Spiders, on the other hand, have only two main body parts: the cephalothorax (a fused head and thorax) and the abdomen. This fusion is more than just structural—it reflects deeper evolutionary divergence. The cephalothorax houses the brain, eyes, mouthparts, and all eight legs, while the abdomen contains vital organs such as the heart, digestive tract, and silk glands.

“Body segmentation is one of the clearest indicators we use in taxonomy. Spiders’ fused cephalothorax immediately sets them apart from true insects.” — Dr. Lila Torres, Arachnologist, University of Colorado

Leg Count and Movement Patterns

All spiders have exactly eight legs. This is a defining feature of the class Arachnida, which includes scorpions, ticks, and mites. If you see a small creature with six legs, it’s an insect. Eight legs? It could be a spider—or another arachnid.

Insects, by definition, have six legs arranged in three pairs. These legs emerge solely from the thorax and are often specialized—for jumping, swimming, or grasping. Spider legs, however, attach to the cephalothorax and are used primarily for walking, sensing vibrations, and capturing prey.

Beyond count, movement also differs. Insects often move with a tripod gait—three legs on the ground at once—while spiders distribute their weight across all eight limbs, allowing for smooth, agile motion across complex terrain like webs or uneven surfaces.

Leg Comparison Table

| Feature | Spiders (Arachnids) | Insects |

|---|---|---|

| Total Legs | 8 | 6 |

| Leg Attachment Point | Cephalothorax | Thorax |

| Leg Specialization | Walking, sensing, web manipulation | Walking, jumping, digging, swimming |

| Presence of Antennae | No antennae | Yes, always present |

Eyes, Sensing, and Nervous System

Another major difference lies in sensory organs. Most insects have compound eyes made up of dozens or even thousands of tiny lenses, providing wide-angle vision. Many also rely heavily on antennae for smell, touch, and detecting air vibrations.

Spiders typically have simple eyes—anywhere from two to eight, depending on the species—but never compound ones. Their vision ranges from poor to surprisingly acute (as in jumping spiders, which can track prey with precision). Instead of antennae, spiders use sensitive hairs on their legs and bodies to detect vibrations, air currents, and chemical cues.

This lack of antennae is a critical identifier. No spider has antennae; all insects do. Even wingless insects like silverfish or fleas have them. This single trait alone can help rule out misclassification in the field.

Classification and Evolutionary Lineage

Both spiders and insects belong to the phylum Arthropoda—animals with exoskeletons, segmented bodies, and jointed appendages. However, they diverge at the class level:

- Insects belong to the class Insecta.

- Spiders belong to the class Arachnida.

This split occurred over 400 million years ago. While some early arthropods gave rise to insects capable of flight and global dispersal, others evolved into arachnids adapted for predation and terrestrial hunting. Spiders developed silk production and venom delivery systems—traits absent in insects.

Unlike insects, spiders do not undergo metamorphosis. They grow through molting, shedding their exoskeleton multiple times throughout life. In contrast, many insects pass through larval, pupal, and adult stages—a process known as complete metamorphosis.

Mini Case Study: Garden Pest Identification

Sarah, a home gardener in Oregon, noticed small creatures on her tomato plants. At first, she assumed they were aphids—tiny green insects that damage crops. But upon closer inspection, she saw eight-legged animals preying on the aphids. A local extension agent confirmed they were jumping spiders.

Because Sarah understood that spiders aren’t insects—and are actually beneficial predators—she avoided using broad-spectrum pesticides. As a result, her garden experienced fewer pest outbreaks naturally. This real-world example shows how accurate identification leads to smarter, eco-friendly decisions.

Common Misconceptions and Why They Matter

One widespread myth is that “all bugs with lots of legs are insects.” This oversimplification leads people to fear or eliminate spiders unnecessarily. In reality, most spiders are harmless to humans and provide valuable pest control by eating flies, mosquitoes, and crop-damaging insects.

Mislabeling spiders as insects also hinders scientific literacy. Students may struggle with biology concepts if foundational taxonomy is misunderstood. For medical professionals, distinguishing between insect bites (like mosquito or flea) and spider envenomation (such as from a brown recluse) is crucial for proper treatment.

Checklist: How to Tell Spiders from Insects

- Count the legs: 6 = insect, 8 = spider.

- Check for antennae: present = insect, absent = spider.

- Observe body segments: 3 parts (head, thorax, abdomen) = insect; 2 parts (cephalothorax + abdomen) = spider.

- Note wing presence: only insects have wings; no spider can fly.

- Watch behavior: web-building is exclusive to spiders (and some rare arachnids).

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all eight-legged creatures spiders?

No. Other arachnids like ticks, mites, and harvestmen (daddy longlegs) also have eight legs but differ from spiders in anatomy and behavior. For example, harvestmen don’t produce silk or venom.

Do spiders ever have six legs?

Adult spiders always have eight legs. However, injured individuals may lose limbs and survive with fewer. Juvenile spiders still develop all eight during growth.

Can insects and spiders interbreed?

Absolutely not. They are genetically too distant, with different chromosome counts, reproductive systems, and evolutionary histories. Cross-breeding is impossible.

Conclusion: Seeing Beyond the Label “Bug”

Recognizing that spiders aren’t insects enriches our understanding of the natural world. It empowers better decision-making in gardening, pest control, education, and health. These distinctions aren’t just academic—they reflect millions of years of evolution and adaptation.

Next time you see a spider in your home or an insect in your garden, take a moment to observe its form. Notice the legs, the body, the eyes. You’re not just looking at a “bug”—you’re witnessing a highly specialized organism shaped by nature’s intricate design.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?