At first glance, a strawberry looks like a classic berry—small, sweet, and packed with seeds. But in the world of botany, appearances can be deceiving. Despite common usage, strawberries are not true berries. In fact, many fruits we casually label as “berries” don’t meet the scientific criteria, while others—like bananas and tomatoes—do. This article unpacks the surprising botanical definition of a berry, explains why strawberries fall short, and reveals which everyday fruits qualify under strict plant science.

What Botanists Mean by “Berry”

In everyday language, “berry” is a loose term applied to small, pulpy fruits like blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries. But botanically, a berry is a specific type of fruit that develops from a single ovary of a flower. It must have three distinct fleshy layers: the exocarp (outer skin), mesocarp (middle layer), and endocarp (inner layer surrounding the seeds). True berries contain two or more seeds embedded within the flesh and form without a stone or pit.

This technical definition excludes many fruits we commonly call berries. For example, blackberries and raspberries are not berries at all—they’re aggregate fruits made up of multiple tiny drupelets, each containing its own seed. Conversely, some unexpected fruits like avocados, eggplants, and even watermelons are classified as berries due to their structure and development.

“Botanical classification isn't about taste or size—it’s about how the fruit forms and what parts of the flower contribute to it.” — Dr. Lydia Chen, Plant Morphologist, University of California

Why Strawberries Don’t Qualify as Berries

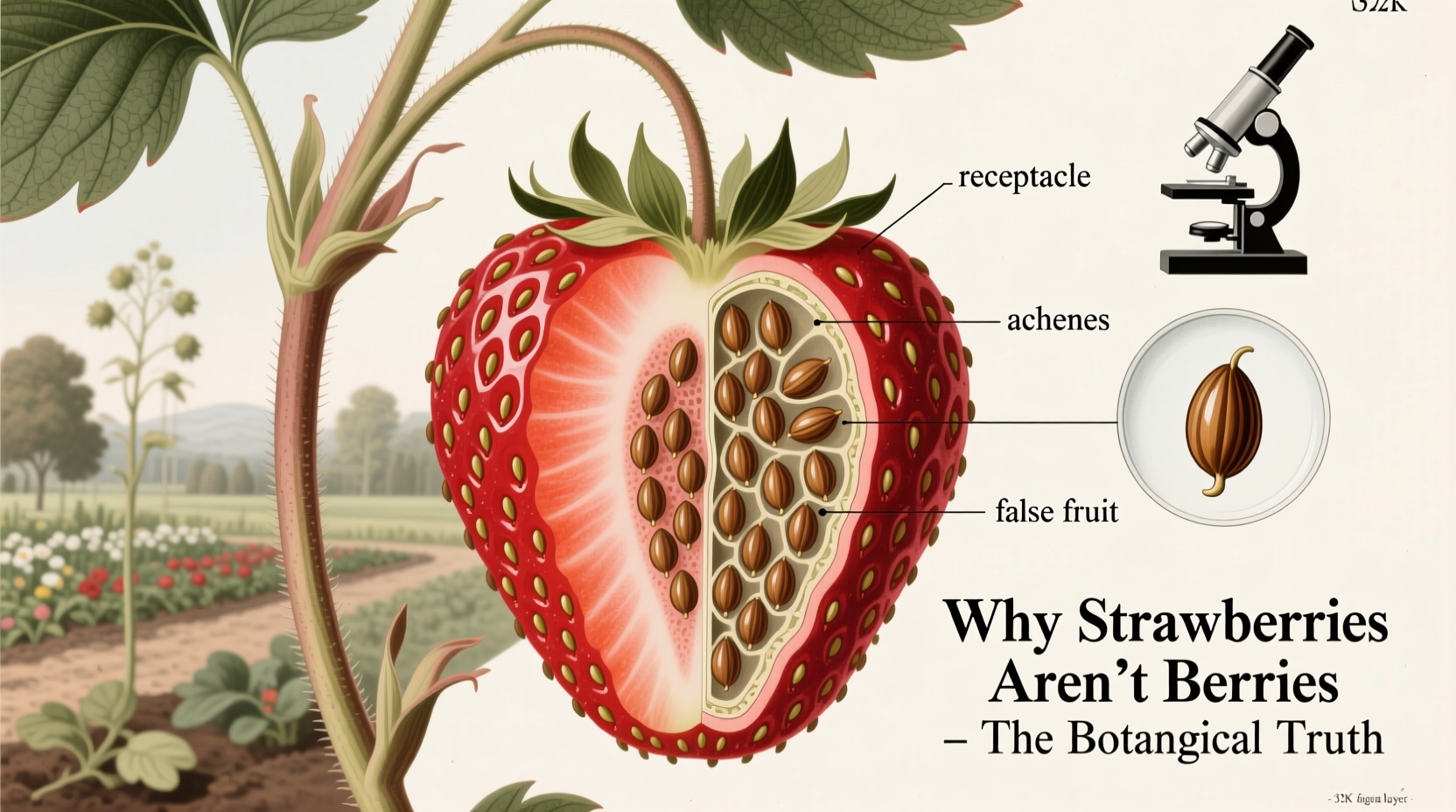

The confusion around strawberries begins with where the seeds are located. Unlike true berries, where seeds are embedded inside the flesh, strawberry seeds are on the outside. Each tiny yellow speck on the surface is actually a separate fruit called an achene—a dry, one-seeded fruit that develops from a single ovule.

More critically, the red, fleshy part of the strawberry we eat isn’t the fruit at all. It’s an enlarged receptacle—the part of the flower stalk that holds the ovaries. The actual fruits are the achenes scattered across the surface. Because the edible portion doesn’t develop from the ovary, and because it hosts multiple independent fruits rather than a single compound fruit, the strawberry fails the botanical test for being a berry.

Fruits That Are Surprisingly True Berries

Some fruits universally accepted as non-berries are, in fact, berries according to botany. Here's a list of common foods that meet the scientific definition:

- Bananas – Develop from a single ovary, have soft internal seeds (often vestigial), and possess all three fleshy fruit layers.

- Tomatoes – Formed from a single flower with one ovary, contain multiple seeds embedded in gelatinous pulp.

- Grapes – Classic example of a true berry: thin skin, juicy middle, and several seeds within.

- Avocados – Though large and oily, they develop from a single ovary and have a fleshy endocarp surrounding a single seed (making them a type of berry called a \"drupe-like berry\").

- Watermelons – A member of the pepo subcategory of berries, with a thick rind and soft interior filled with seeds.

The key takeaway? Size, flavor, and seed count don’t determine berry status—only floral anatomy does.

True Berries vs. Common Misconceptions

| True Berries (Botanical) | Not Berries (Despite Common Use) |

|---|---|

| Banana | Strawberry |

| Tomato | Raspberry |

| Grape | Blackberry |

| Blueberry | Boysenberry |

| Watermelon | Cranberry* |

*Note: Cranberries are an exception—they are true botanical berries but often excluded from casual use due to tartness and culinary role.

How Fruit Classification Works: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Understanding whether a fruit is a berry requires tracing its development from flower to maturity. Here’s how botanists classify fruits systematically:

- Identify the flower structure: Determine how many ovaries are present. Berries come from flowers with a single ovary.

- Analyze fruit formation: Check if the fruit develops solely from the ovary tissue. If other parts (like the receptacle) become fleshy, it may not be a berry.

- Examine seed placement: Seeds should be enclosed within the fruit’s flesh, not on the exterior.

- Assess fruit layers: Look for the presence of exocarp, mesocarp, and endocarp. Their development confirms berry classification.

- Compare to known categories: Match the fruit to established types—berry, drupe, pome, aggregate, etc.

This process reveals why apples are not berries (they’re pomes, with core tissue derived from the floral tube), and why pineapples—though clustered—are multiple fruits fused from many flowers, not single berries.

Real-World Example: Teaching Botany in the Classroom

In a high school biology class in Portland, Oregon, teacher Marcus Hale used grocery-store fruits to challenge students’ assumptions. He handed out strawberries, bananas, tomatoes, and blueberries, asking students to guess which were true berries. Most confidently labeled strawberries and blueberries as berries, dismissing tomatoes entirely.

After dissecting each fruit and reviewing flower diagrams, students discovered that the banana and tomato met all botanical criteria, while the strawberry did not. One student remarked, “I thought I knew fruit, but now I realize I’ve been wrong my whole life.” The lesson not only clarified classification but sparked interest in plant science beyond the curriculum.

Expert Insight on Naming Confusion

The gap between scientific terminology and everyday language causes persistent confusion. Experts emphasize that both uses are valid—just different in context.

“The word ‘berry’ in supermarkets means ‘small, edible fruit.’ In botany, it’s a precise morphological term. Neither is wrong—they serve different purposes.” — Dr. Elena Rodriguez, Director of the Botanical Education Initiative, New York Botanical Garden

This duality reflects broader patterns in science communication. Just as “nut” in casual speech includes almonds and cashews (which are drupes), fruit names often prioritize cultural familiarity over taxonomic accuracy.

FAQ

Are blueberries real berries?

Yes, blueberries are true botanical berries. They develop from a single ovary, have seeds embedded in the flesh, and exhibit the three fleshy fruit layers characteristic of berries.

If strawberries aren’t berries, what are they?

Strawberries are classified as “aggregate accessory fruits.” “Aggregate” because they consist of many small fruits (the achenes), and “accessory” because the fleshy part comes from the receptacle, not the ovary.

Is a cucumber a berry?

Yes, cucumbers are botanical berries. They develop from a single ovary, contain multiple seeds, and have a fleshy interior. Like tomatoes and melons, they belong to the pepo category of berries with a hard outer rind.

Conclusion

The idea that strawberries aren’t berries highlights the fascinating disconnect between common language and scientific precision. While it won’t change how we enjoy our summer fruit salads, understanding the botanical truth deepens appreciation for plant diversity and the logic behind classification. Nature doesn’t conform to human labels—it operates on evolutionary and structural principles far more intricate than naming conventions suggest.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?