Turtles are among the most ancient and enigmatic creatures on Earth, with fossil records dating back over 220 million years. Despite their unique appearance—encased in a protective shell and often associated with slow movement—turtles share fundamental biological traits with other reptiles. Understanding why turtles are classified as reptiles requires examining their anatomy, physiology, reproduction, and evolutionary lineage. This article explores the scientific basis behind their classification, clarifying misconceptions and highlighting the characteristics that firmly place turtles within the class Reptilia.

Anatomical Traits That Define Reptiles

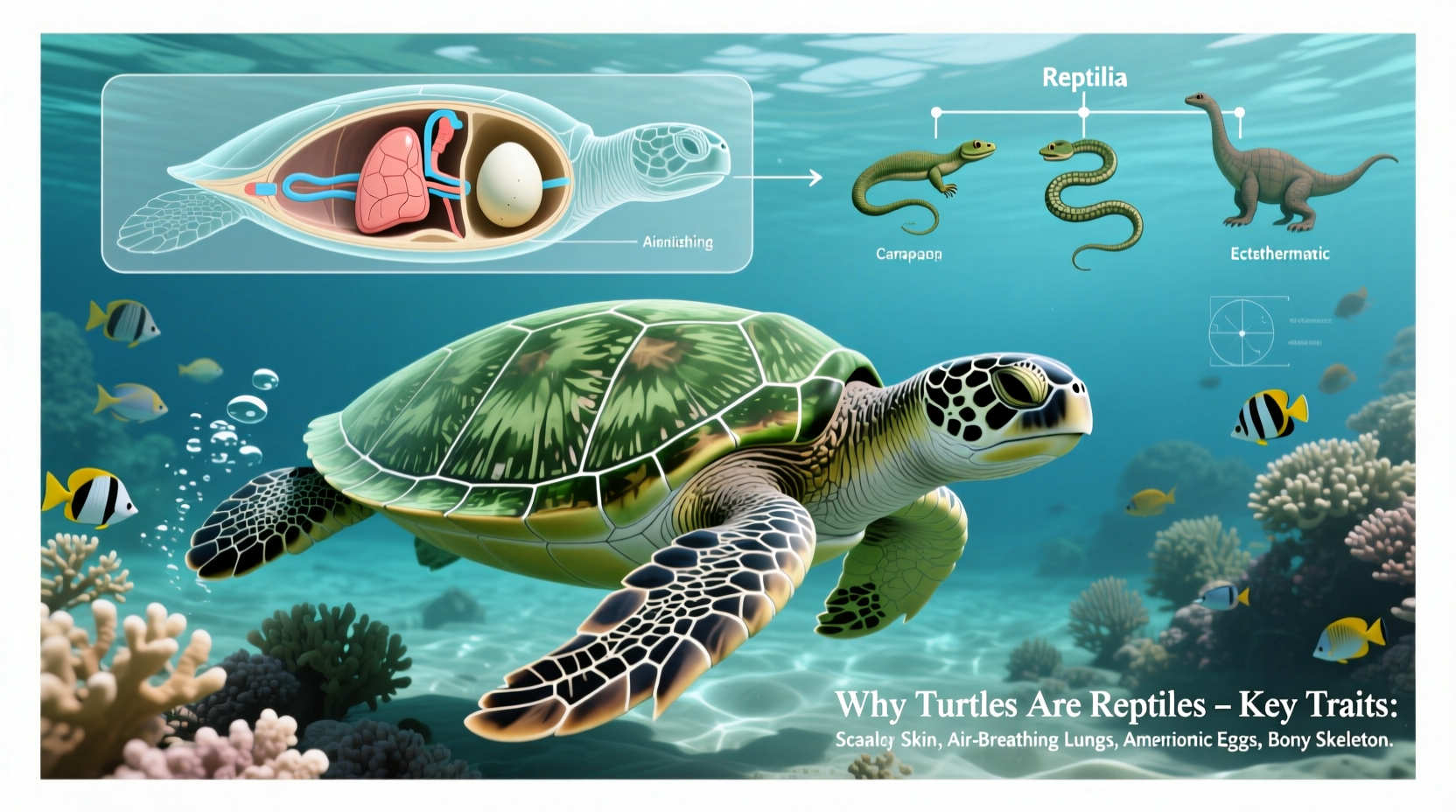

All reptiles share a set of defining anatomical features, and turtles meet every criterion. These include:

- Cold-blooded metabolism (ectothermy): Turtles rely on external heat sources to regulate body temperature, just like lizards, snakes, and crocodilians.

- Scaly skin: Their skin is covered in keratinized scales, which reduce water loss and provide protection.

- Lungs for respiration: Unlike amphibians, turtles breathe exclusively through lungs throughout their lives.

- Amniotic eggs: They lay eggs with protective membranes that allow development on land, a key trait separating reptiles from amphibians.

The turtle’s shell, often mistaken as a separate structure, is actually an integral part of its skeleton—formed from fused ribs and vertebrae. The outer surface is covered in scutes, which are made of keratin, the same protein found in human nails and lizard scales. This reinforces their identity as scaled reptiles, even if the scale pattern is less obvious than in snakes or geckos.

Reproductive Biology: A Key Reptilian Feature

One of the most definitive traits placing turtles in the reptile category is their reproductive strategy. Like all reptiles, turtles reproduce by laying amniotic eggs. These eggs contain specialized membranes—the amnion, chorion, allantois, and yolk sac—that protect the developing embryo from desiccation and allow gas exchange in terrestrial environments.

Females typically dig nests in soil or sand, where they deposit hard-shelled or leathery eggs depending on the species. Sea turtles, for example, travel great distances to return to nesting beaches, burying clutches of over 100 eggs. Once laid, the eggs are left to incubate without parental care—a behavior common among reptiles but distinct from most birds and mammals.

Temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) is another reptilian characteristic observed in many turtle species. The incubation temperature of the nest determines whether hatchlings develop as males or females. For instance, in many freshwater turtles, cooler temperatures produce males, while warmer ones yield females. This phenomenon is widespread among reptiles but absent in amphibians and mammals.

Evolutionary Lineage and Genetic Evidence

Historically, the classification of turtles posed a puzzle due to their highly modified anatomy. Some early biologists speculated that turtles were anapsids—primitive reptiles with no temporal openings in the skull—and thus distantly related to modern reptiles. However, advances in molecular phylogenetics have clarified their position.

Modern DNA analysis confirms that turtles are diapsid reptiles, closely related to birds, crocodilians, and squamates (lizards and snakes). Though adult turtles lack visible temporal fenestrae (skull openings), embryological studies reveal that these structures form during development before being enclosed by bone. This developmental pattern aligns them with diapsid ancestry.

“Genomic data now overwhelmingly support turtles as nested within Diapsida, making them evolutionary cousins to crocodiles and birds.” — Dr. Jennifer Graves, Evolutionary Biologist, Australian National University

This genetic insight has reshaped taxonomy. Turtles are now classified under the clade Archelosauria, which unites them with archosaurs (crocodilians and birds). Far from being “living fossils” outside mainstream reptile evolution, turtles are deeply embedded in the reptilian family tree.

Comparative Table: Turtles vs. Amphibians vs. Other Reptiles

| Feature | Turtles | Amphibians (e.g., frogs) | Other Reptiles (e.g., lizards) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin Type | Keratinized scales and scutes | Moist, glandular, permeable skin | Dry, scaly skin |

| Thermoregulation | Ectothermic | Ectothermic | Ectothermic |

| Respiration | Lungs only (adults) | Lungs, skin, gills (larval) | Lungs only |

| Egg Type | Amniotic, shelled | Gelatinous, no shell | Amniotic, leathery/hard shell |

| Habitat Range | Aquatic, terrestrial, marine | Mostly freshwater/moist land | Terrrestrial, arboreal, aquatic |

| Larval Stage | None – direct development | Yes (tadpole stage) | None |

This comparison underscores that while turtles may appear unusual, their core biological systems align completely with reptilian norms—especially when contrasted with amphibians, which undergo metamorphosis and depend on water for reproduction.

Common Misconceptions About Turtles and Reptiles

Several myths persist about turtles that lead people to question their reptilian status:

- “Turtles are amphibians because they live in water.” While some turtles spend most of their time in water, habitat does not determine classification. Respiration method and reproduction do. Aquatic turtles still lay eggs on land and breathe air—unlike amphibians like salamanders, which can absorb oxygen through their skin underwater.

- “They don’t look like other reptiles, so they must be different.” Appearance can be misleading. Evolution has led to extreme adaptations in many animal groups. Whales don’t look like other mammals, yet they are fully classified as such. Similarly, the turtle’s shell is a remarkable adaptation, not a taxonomic outlier.

- “Baby turtles hatch with gills.” False. Turtle hatchlings emerge with fully functional lungs and must reach the surface to breathe immediately. There is no aquatic larval phase.

Mini Case Study: The Snapping Turtle in Suburban Wetlands

In central Illinois, a population of common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) thrives in a restored wetland surrounded by residential neighborhoods. Local residents once believed these animals were large amphibians due to their frequent submersion and muddy appearance. Wildlife educators intervened, demonstrating how the turtles bask on logs to thermoregulate (a classic reptilian behavior), lay eggs in roadside banks, and never exhibit gills or metamorphosis. Over time, community perception shifted, and the turtles became recognized as native reptiles playing a vital role in ecosystem balance by scavenging and controlling fish populations.

Checklist: How to Identify a Reptile (Using Turtles as an Example)

Use this checklist to determine whether an animal belongs to the reptile class:

- Does it have dry, scaly skin or protective keratin structures? ✅ (Turtle scutes)

- Is it ectothermic, relying on external heat sources? ✅

- Does it breathe air using lungs throughout life? ✅

- Does it lay amniotic eggs on land? ✅

- Is there no aquatic larval stage or metamorphosis? ✅

- Is its heart three-chambered (with partial separation)? ✅ (Most reptiles, including turtles)

If all answers are yes, the animal is a reptile—regardless of shell, speed, or habitat preference.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are sea turtles reptiles or fish?

Sea turtles are reptiles, not fish. Although they live in the ocean and swim efficiently, they breathe air, lay eggs on beaches, and have scales and skeletons consistent with reptilian biology. Fish, in contrast, extract oxygen from water via gills and typically fertilize eggs externally.

Do all reptiles have shells?

No. The shell is unique to turtles and evolved as a defensive adaptation. Other reptiles rely on speed, camouflage, venom, or spines for protection. The presence of a shell doesn’t exclude turtles from Reptilia—it simply highlights evolutionary diversity within the group.

Can turtles survive freezing temperatures?

Some terrestrial turtles, like the box turtle, can endure cold climates by brumating underground. During brumation, their metabolism slows dramatically, allowing survival in near-freezing conditions. This ability reflects reptilian adaptability, not a departure from reptilian traits.

Conclusion: Embracing the Reptilian Identity of Turtles

Turtles are not just reptiles—they are exemplary models of reptilian evolution. Their longevity, physiological adaptations, and deep genetic ties to other reptiles underscore a shared biological blueprint. From their scaly skin and lung-based respiration to their amniotic eggs and ectothermic nature, every major trait aligns with the definition of Reptilia. Misunderstandings often arise from their unique shell or aquatic habits, but these are variations on a theme, not exceptions to the rule.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?