Labor Day in the United States is more than just a long weekend or the unofficial end of summer. It is a federally recognized holiday that honors the contributions and achievements of American workers. But behind the barbecues, parades, and retail sales lies a rich and often turbulent history rooted in the labor movement of the 19th century. Understanding why Labor Day was invented requires a journey through industrialization, worker exploitation, union activism, and political compromise. This article explores the origins, evolution, and formal recognition of Labor Day, shedding light on the social forces that shaped one of America’s most significant civic holidays.

The Industrial Backdrop: A Nation at Work

In the late 1800s, the United States was undergoing rapid industrialization. Factories, railroads, and mines expanded across the country, fueling economic growth but also creating harsh working conditions. Workers—many of them immigrants, women, and children—often labored 12 to 16 hours a day, six or seven days a week, for meager wages. Safety standards were nearly nonexistent, and job-related injuries were common.

These grueling conditions sparked widespread unrest. Labor unions began forming to advocate for better pay, shorter hours, and safer workplaces. The struggle was not just economic but deeply human—a fight for dignity in the face of industrial indifference. As union activity grew, so did public awareness of the need to recognize and protect the rights of workers.

The Birth of Labor Day: Origins and Early Celebrations

The exact origin of Labor Day remains a subject of debate, but two key figures are often credited: Peter McGuire and Matthew Maguire.

- Peter McGuire, a carpenter and co-founder of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), is traditionally credited with proposing a day to honor workers during a meeting of the Central Labor Union in New York in 1882.

- Matthew Maguire, a machinist and secretary of the same union, has gained increasing recognition in recent decades as the true originator of the idea, particularly after historical research by the New York State Senate in the 1970s.

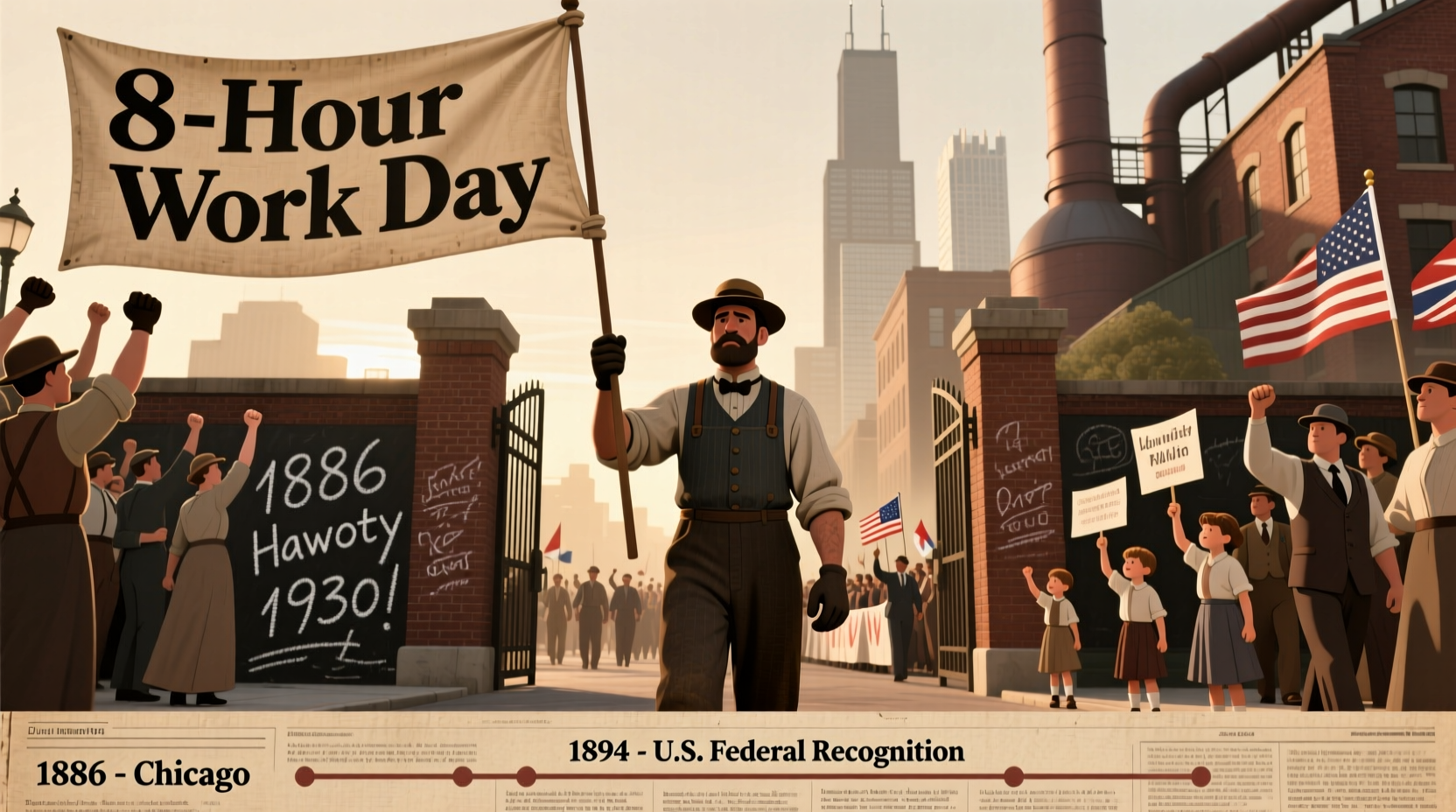

On September 5, 1882, the first Labor Day parade took place in New York City. Organized by the Central Labor Union, it featured over 10,000 workers who marched from City Hall to Union Square under the slogan “Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Rest, Eight Hours for Recreation.” The event was both a demonstration and a celebration—a public assertion of workers’ value to society.

“Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed.” — Abraham Lincoln, 1861

A Growing Movement: From Local Event to National Holiday

The success of the 1882 parade inspired other cities to adopt similar celebrations. By 1887, Oregon became the first state to make Labor Day an official public holiday. Over the next few years, Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York followed suit.

However, it was a wave of labor unrest—not peaceful parades—that ultimately pushed the federal government to act. The Pullman Strike of 1894, a nationwide railroad boycott led by Eugene V. Debs and the American Railway Union, paralyzed much of the country’s rail traffic. In response, President Grover Cleveland deployed federal troops to break the strike, leading to violent clashes and the deaths of several workers.

Fearing further alienation of the working class, especially ahead of the upcoming election, Congress moved quickly to pass legislation establishing Labor Day as a national holiday. Just six days after the end of the Pullman Strike, on June 28, 1894, President Cleveland signed the bill into law, designating the first Monday in September as a legal holiday dedicated to the labor force.

This move was widely seen as a political gesture to mend relations with organized labor, though it also acknowledged the growing influence of unions in American life.

Timeline of Key Events in Labor Day's Recognition

- 1882: First Labor Day parade held in New York City on September 5.

- 1887: Oregon becomes the first state to legally recognize Labor Day.

- 1894: Over 30 states already celebrate Labor Day; federal legislation passes after the Pullman Strike.

- June 28, 1894: President Grover Cleveland signs Labor Day into law as a national holiday.

- Present Day: Observed annually on the first Monday in September across all 50 states.

How Labor Day Differs Around the World

While the U.S. celebrates Labor Day in September, much of the world—including over 80 countries—observes International Workers' Day on May 1. Also known as May Day, this date commemorates the Haymarket Affair of 1886 in Chicago, a pivotal event in the fight for the eight-hour workday that turned tragic when a bomb exploded during a labor rally, killing several police officers and civilians.

The U.S. decision to distance Labor Day from May 1 was deliberate. Leaders like President Cleveland wanted to avoid associating the holiday with radicalism or socialist movements linked to the Haymarket incident. Instead, Labor Day was framed as a non-confrontational, family-friendly celebration of work and productivity.

| Feature | U.S. Labor Day (September) | International Workers' Day (May 1) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | New York labor parade (1882) | Haymarket Affair (1886) |

| Political Tone | Non-confrontational, patriotic | Often tied to labor rights protests |

| Global Observance | Limited to U.S. and a few others | Widely observed in Europe, Asia, Latin America |

| Common Activities | Parades, barbecues, retail sales | Protests, rallies, union marches |

Modern Recognition and Cultural Significance

Today, Labor Day is celebrated across the United States with community events, fireworks, and family gatherings. It marks the symbolic end of summer and the beginning of the school year for many. Retailers offer major sales, and travel peaks as people take advantage of the three-day weekend.

Yet beyond the festivities, the holiday continues to serve as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for fair wages, workplace safety, and workers’ rights. Issues such as the gender pay gap, gig economy protections, and minimum wage debates keep the spirit of labor advocacy alive.

Unions still play a vital role. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 10% of American workers belong to a union, with higher rates in sectors like education, public administration, and transportation. While union membership has declined since its mid-20th-century peak, recent organizing efforts at companies like Amazon and Starbucks signal a resurgence of labor consciousness among younger workers.

Real Example: The 2023 UPS Contract Negotiations

In the summer of 2023, the Teamsters union negotiated a new contract with UPS covering over 340,000 workers. With the threat of a strike looming just before Labor Day, the agreement included significant gains: higher wages, improved working conditions, and a pathway to full-time status for part-time employees. The timing underscored how Labor Day remains symbolically tied to real labor negotiations and worker power—even in the modern economy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Labor Day in September instead of May?

The U.S. chose September to distance the holiday from International Workers’ Day on May 1, which is associated with the radical labor movements and the Haymarket Affair. The September date originated with a New York labor parade in 1882 and was later adopted nationally to avoid political controversy.

Who gets the day off on Labor Day?

Most federal and state employees, as well as workers in industries like education and banking, receive Labor Day as a paid holiday. However, essential service workers—such as those in healthcare, retail, and transportation—may be required to work, often with overtime pay.

Is Labor Day only for union workers?

No. Although the holiday originated within the labor union movement, it now honors all workers, including non-union employees, freelancers, and gig workers. Its purpose is to recognize the collective contribution of the American workforce to the strength and prosperity of the nation.

Conclusion: Honoring the Legacy, Shaping the Future

Labor Day was invented not as a mere day off, but as a hard-won acknowledgment of the dignity and value of work. Born from protest, shaped by tragedy, and codified by politics, it stands as a testament to the enduring power of collective action. While the parades may have grown quieter and the political edge somewhat dulled, the core message remains: workers are the foundation of the economy and deserve respect, fair treatment, and safe conditions.

As we enjoy the long weekend, let us remember the men and women who fought for basic rights we often take for granted—the eight-hour day, child labor laws, and workplace safety regulations. Their legacy lives on every time we clock out at five, receive a paycheck, or take a lunch break.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?