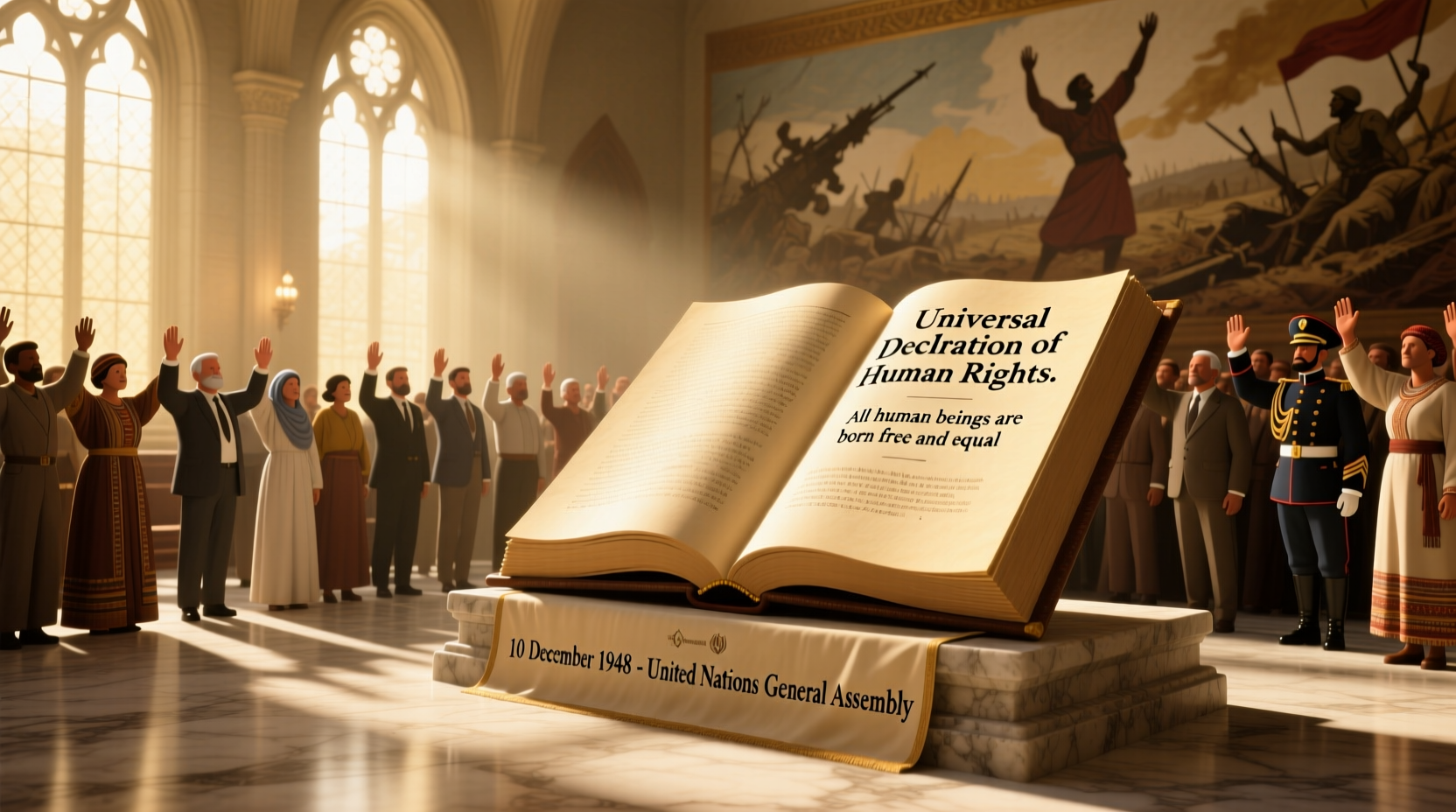

In the aftermath of World War II, the world stood at a moral crossroads. The horrors of genocide, mass displacement, and systemic oppression had laid bare the consequences of unchecked state power and the absence of universally recognized human rights. In response, the international community came together to establish a foundational document that would affirm the inherent dignity of every person. This effort culminated in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948. But why was this declaration necessary? What historical forces shaped its creation, and what enduring purpose does it serve?

The Historical Context: A World Reeling from War

The devastation of World War II left an indelible mark on global consciousness. Over 70 million people lost their lives, including six million Jews systematically murdered in the Holocaust. Concentration camps, forced labor, torture, and the suppression of political dissent revealed how easily civil liberties could be dismantled under authoritarian regimes.

As peace negotiations concluded, leaders recognized that preventing future conflicts required more than just political treaties or military alliances. A new moral and legal framework was needed—one that established clear, non-negotiable standards for how individuals should be treated, regardless of nationality, race, religion, or government.

The newly formed United Nations, established in 1945, took on the responsibility of defining these standards. One of its first major tasks was the creation of a universal statement of human rights that could guide nations in rebuilding societies based on justice, equality, and respect.

A Response to Totalitarianism and Systemic Injustice

One of the primary reasons for creating the UDHR was to confront the ideologies that had fueled Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and other oppressive regimes. These governments had justified atrocities by denying basic rights to certain groups—labeling them as \"inferior\" or \"enemies of the state.\"

The declaration aimed to dismantle such hierarchies by asserting that rights are not granted by governments but are inherent to all human beings simply by virtue of being human. Article 1 of the UDHR captures this principle: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

This philosophical shift—from rights as privileges bestowed by rulers to rights as universal entitlements—was revolutionary. It challenged colonial powers, dictatorships, and discriminatory legal systems around the world to align their practices with a higher standard of human decency.

“We need a global standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations.” — Eleanor Roosevelt, Chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights

The Role of the Drafting Committee and Global Collaboration

The drafting process itself reflected the universality the document sought to promote. Chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, the UN Commission on Human Rights included representatives from diverse cultural, religious, and legal backgrounds—such as René Cassin (France), P.C. Chang (China), Charles Malik (Lebanon), and John Humphrey (Canada).

These experts worked to balance Western liberal ideals with philosophies from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. For example, while individual freedoms were emphasized, input from non-Western members ensured recognition of communal responsibilities and social welfare as integral to human dignity.

The final document was not legally binding, but its moral authority was intended to inspire constitutions, laws, and social movements worldwide. By grounding rights in shared human values rather than any single legal tradition, the UDHR became a bridge across civilizations.

Timeline of Key Events Leading to the UDHR's Adoption

- 1945: United Nations founded; Charter includes commitment to human rights.

- 1946: UN Commission on Human Rights established.

- 1947–1948: Drafting committee collects input from governments and organizations worldwide.

- December 10, 1948: UDHR adopted by UN General Assembly with 48 votes in favor, 0 against, and 8 abstentions.

Core Principles Enshrined in the Declaration

The UDHR consists of 30 articles that articulate fundamental rights across civil, political, economic, social, and cultural domains. Some of the most significant include:

- Article 3: Right to life, liberty, and security of person.

- Article 5: Prohibition of torture and cruel or degrading treatment.

- Article 9: Protection against arbitrary arrest or exile.

- Article 18: Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

- Article 25: Right to an adequate standard of living, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care.

These provisions responded directly to wartime abuses. For instance, Article 9 addressed the Soviet practice of sending citizens to gulags without trial, while Article 25 countered the widespread poverty and deprivation experienced during and after the war.

| Human Right | Historical Abuse It Addresses | Long-Term Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Freedom from Slavery (Art. 4) | Forced labor in concentration camps | Basis for modern anti-trafficking laws |

| Right to Asylum (Art. 14) | Refugee crises due to persecution | Framework for international refugee protection |

| Right to Education (Art. 26) | Denial of schooling under apartheid and colonial rule | Influenced national education policies globally |

Legacy and Ongoing Relevance

The UDHR has become the cornerstone of international human rights law. Though not a treaty itself, it has inspired over 70 human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

Courts around the world cite the declaration when interpreting constitutional protections. Activists invoke it to challenge injustice, from apartheid in South Africa to gender discrimination in Afghanistan. Even states that never ratified later treaties often feel compelled to justify their actions in light of the UDHR’s principles.

Mini Case Study: The Anti-Apartheid Movement in South Africa

In the mid-20th century, South Africa’s apartheid regime institutionalized racial segregation and denied Black citizens basic rights. Activists like Nelson Mandela and organizations such as the African National Congress used the UDHR to expose these violations on the global stage.

At the 1955 Congress of the People, they adopted the Freedom Charter, which echoed the language of the UDHR: “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white.” International pressure, fueled by appeals to the declaration, contributed to sanctions and eventually the end of apartheid in 1994.

This example illustrates how a non-binding document can wield immense influence when aligned with moral courage and collective action.

FAQ

Is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights legally binding?

No, the UDHR itself is not a treaty and does not create legal obligations for countries. However, many of its provisions have since become part of customary international law and binding treaties, making them enforceable in practice.

Why did some countries abstain from voting on the UDHR in 1948?

Eight nations abstained, including the Soviet Union and several of its allies, who argued that the declaration interfered with national sovereignty and did not place enough emphasis on duties to the state. Saudi Arabia abstained due to concerns about religious freedom and gender equality clauses.

How is the UDHR relevant today?

The declaration continues to guide responses to modern challenges such as digital privacy, climate-induced displacement, and AI ethics. Its principles are cited by the UN, NGOs, and courts when advocating for justice in emerging contexts.

Checklist: How to Apply the UDHR in Everyday Advocacy

- Learn the 30 articles of the UDHR and identify which are most relevant to your community.

- Monitor local laws and policies for compliance with fundamental rights.

- Support organizations working to protect vulnerable populations.

- Use the UDHR in public discourse, education, and media to hold authorities accountable.

- Participate in Human Rights Day (December 10) events to raise awareness.

Conclusion

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created not merely as a reaction to past horrors, but as a proactive vision for a more just and humane world. Born from the ashes of war, it stands as a testament to what humanity can achieve when it chooses dignity over division, and compassion over cruelty.

Its creation was driven by the urgent need to prevent future atrocities, to restore faith in justice, and to unite diverse cultures around shared ethical principles. More than seven decades later, the UDHR remains a living document—one that calls each generation to defend rights, challenge oppression, and expand the circle of inclusion.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?