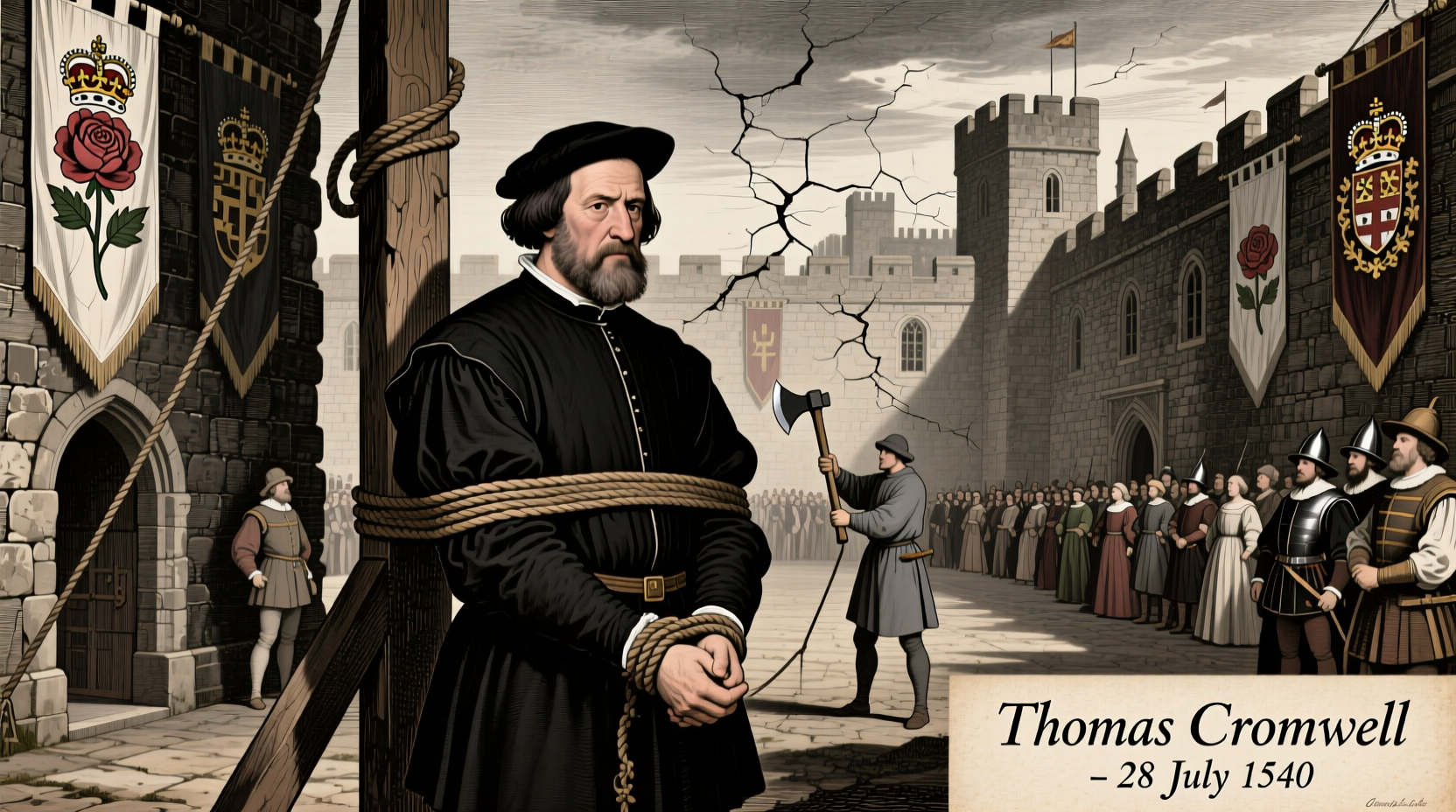

On July 28, 1540, Thomas Cromwell, once the most influential man in England after King Henry VIII, stood on a scaffold at Tower Hill. Once the architect of the English Reformation, the mastermind behind the dissolution of the monasteries, and the king’s chief minister, he now faced execution without trial—condemned by an Act of Attainder. His downfall was swift, brutal, and emblematic of the perilous nature of Tudor politics. To understand why Thomas Cromwell was executed is to step into a world of shifting alliances, religious revolution, and the volatile will of a king determined to control both church and state.

The Rise of a Commoner

Thomas Cromwell began life in relative obscurity, the son of a blacksmith and cloth worker in Putney. He did not inherit privilege or title. Instead, he earned his place through intelligence, administrative skill, and an uncanny ability to anticipate the king’s desires. After serving Cardinal Wolsey, Cromwell entered royal service and quickly became indispensable to Henry VIII.

His ascent coincided with one of the most transformative periods in English history. When Henry sought to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon—a move blocked by the Pope—Cromwell devised a legal and theological framework that severed England from papal authority. Through acts like the Act of Supremacy (1534), which declared Henry Supreme Head of the Church of England, Cromwell engineered a revolution from within the machinery of government.

“Cromwell was the king’s fixer. Where others saw obstacles, he saw solutions—and he delivered them with cold efficiency.” — Diarmaid MacCulloch, Historian and Biographer of Thomas Cromwell

By the late 1530s, Cromwell had amassed unprecedented power: Lord Privy Seal, Vicegerent in Spirituals, and effectively the head of both church and state administration. But such power, especially when wielded by a man of low birth, bred resentment among the nobility and suspicion among traditionalists.

The Path to Downfall: Key Factors

Cromwell’s execution was not the result of a single mistake but a cascade of political missteps, external pressures, and fatal miscalculations. Several interlocking factors led to his ruin:

- Religious Reform Overreach: Cromwell pushed Protestant reforms aggressively, dissolving monasteries, suppressing shrines, and promoting English Bibles. This alienated conservative factions, including powerful nobles and much of the population outside London.

- The Anne of Cleves Marriage: In an effort to secure a Protestant alliance, Cromwell arranged Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves in 1540. The king found her physically unattractive and called it a “disgraceful” union. Cromwell’s failure here undermined his credibility at court.

- Rising Opposition: Nobles like the Duke of Norfolk and Bishop Stephen Gardiner resented Cromwell’s influence. They seized on the failed marriage to turn Henry against him.

- Henry’s Volatility: The king was increasingly paranoid, ill, and prone to sudden shifts in favor. Loyalty meant little if utility waned.

- Lack of Personal Loyalty Network: Unlike aristocrats, Cromwell could not rely on blood ties or noble alliances. His power rested solely on the king’s trust—a fragile foundation.

A Timeline of Collapse: From Power to Prison

Cromwell’s fall occurred over mere weeks. A clear sequence reveals how quickly fortune turned:

- January 6, 1540: Henry VIII marries Anne of Cleves.

- February–April 1540: The king expresses dissatisfaction with the marriage; courtiers begin undermining Cromwell.

- June 10, 1540: Cromwell is arrested at a council meeting and charged with treason and heresy.

- Attainder Passed: Parliament declares him guilty without trial, citing charges of corruption, heresy, and attempting to marry Lady Mary (the future Queen Mary I).

- July 28, 1540: Executed at Tower Hill. Reports suggest the beheading was botched, taking multiple strokes.

Notably, the same day Cromwell died, Henry married Catherine Howard—orchestrated by his enemies. The timing was no coincidence. It signaled a shift back toward conservative Catholic influences at court.

Charges Against Cromwell: Truth or Fabrication?

The official indictment accused Cromwell of:

- Treason for allegedly plotting to seize power

- Heresy for supporting radical Protestant teachings

- Abuse of power during the dissolution of the monasteries

- Attempting to arrange a marriage between himself and Princess Mary

Modern historians widely regard these charges as exaggerated or outright false. There is no credible evidence that Cromwell conspired against the king. The claim about marrying Mary was particularly absurd—he was a reformer, and aligning with the staunchly Catholic princess would have been politically suicidal.

| Charge | Evidence | Historical Consensus |

|---|---|---|

| Treason | None documented beyond accusations | Fabricated to justify removal |

| Heresy | He promoted reformist preachers | Politically motivated; reform was once royal policy |

| Corruption | Allegations of financial misconduct | Common accusation; never proven |

| Plotting to marry Princess Mary | No correspondence or testimony supports this | Implausible and likely invented |

The truth is simpler: Cromwell had become too powerful, too controversial, and no longer useful. With the Cleves marriage failing and conservative forces regaining strength, eliminating him served both political expediency and royal ego.

Mini Case Study: The Fall of a Modern Advisor

In 2019, a senior policy advisor in a European government was dismissed abruptly after a major legislative proposal failed. Like Cromwell, this advisor had risen from modest origins, relied solely on competence, and made powerful enemies through reform. Colleagues noted that while technically brilliant, the advisor neglected court politics—failing to build coalitions or soften opposition.

The parallel is striking. Just as Cromwell assumed that delivering results would guarantee survival, modern professionals often underestimate the importance of relationships and perception. In hierarchical systems—whether Tudor courts or modern bureaucracies—technical success is rarely enough. Power requires protection.

Lessons from Cromwell’s Execution

What can we learn from the fate of one of history’s most effective yet doomed administrators?

“Cromwell’s tragedy was that he believed in institutions and process. But in a system where one man holds absolute power, process means nothing when the ruler turns away.” — Suzannah Lipscomb, Tudor Historian

Checklist: Avoiding Political Peril in High-Stakes Environments

- ✅ Regularly assess who feels threatened by your success

- ✅ Cultivate allies across factions, not just superiors

- ✅ Never assume loyalty based on past performance

- ✅ Monitor shifts in leadership mood and priorities

- ✅ Document decisions and protect your reputation proactively

- ✅ Know when to step back before being pushed

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Thomas Cromwell guilty of the crimes he was accused of?

No credible historical evidence supports the charges of treason or heresy. Most scholars view the accusations as politically motivated fabrications designed to remove him from power.

Did Henry VIII regret executing Cromwell?

Within months, Henry reportedly expressed regret, saying he had lost a loyal servant. However, he took no action to reverse the attainder or restore Cromwell’s reputation. His remorse may have been more about losing a competent administrator than moral reflection.

How did Cromwell’s death affect the English Reformation?

His execution marked a temporary setback for Protestant reform. Conservative forces gained influence, leading to the Act of Six Articles (1539), which reinforced Catholic doctrine. However, the structural changes Cromwell implemented—especially the break with Rome and dissolution of monasteries—proved irreversible.

Conclusion: Power, Service, and the Price of Loyalty

Thomas Cromwell’s execution was not merely a personal tragedy but a stark lesson in the fragility of power in autocratic systems. He transformed England’s religious and political landscape more than any other minister of his time, yet his legacy was nearly erased by those who succeeded him. His story reminds us that effectiveness does not guarantee survival—especially when power rests in the hands of one unpredictable individual.

Today, leaders, advisors, and change-makers can learn from Cromwell’s brilliance and his blind spots. Vision and execution matter, but so do diplomacy, humility, and awareness of the human dynamics behind every institution. In the end, the fall of Thomas Cromwell was not due to guilt—but to the timeless dangers of rising too fast, making too many enemies, and serving a king who valued obedience above all.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?