In the aftermath of the American Civil War, the United States faced a profound transformation. The abolition of slavery through the 13th Amendment in 1865 legally freed over four million enslaved African Americans. Yet, freedom did not equate to equality. Across the Southern states, new laws emerged that sought to restrict the liberties of newly emancipated Black citizens. These laws—known as the Black Codes—were neither accidental nor isolated. They were deliberate attempts to preserve the racial hierarchy that had underpinned the antebellum South. Understanding why these codes were created requires examining the historical, economic, and political forces at play during Reconstruction.

The Historical Context: A Nation in Transition

Following the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865, the federal government initiated Reconstruction—a period aimed at reintegrating Southern states into the Union and redefining the status of formerly enslaved people. While emancipation dismantled the legal structure of slavery, Southern elites feared economic collapse without a captive labor force. Plantation owners relied on cheap, coerced labor to sustain cotton and tobacco production. With slavery abolished, they sought alternative means to maintain control over Black workers.

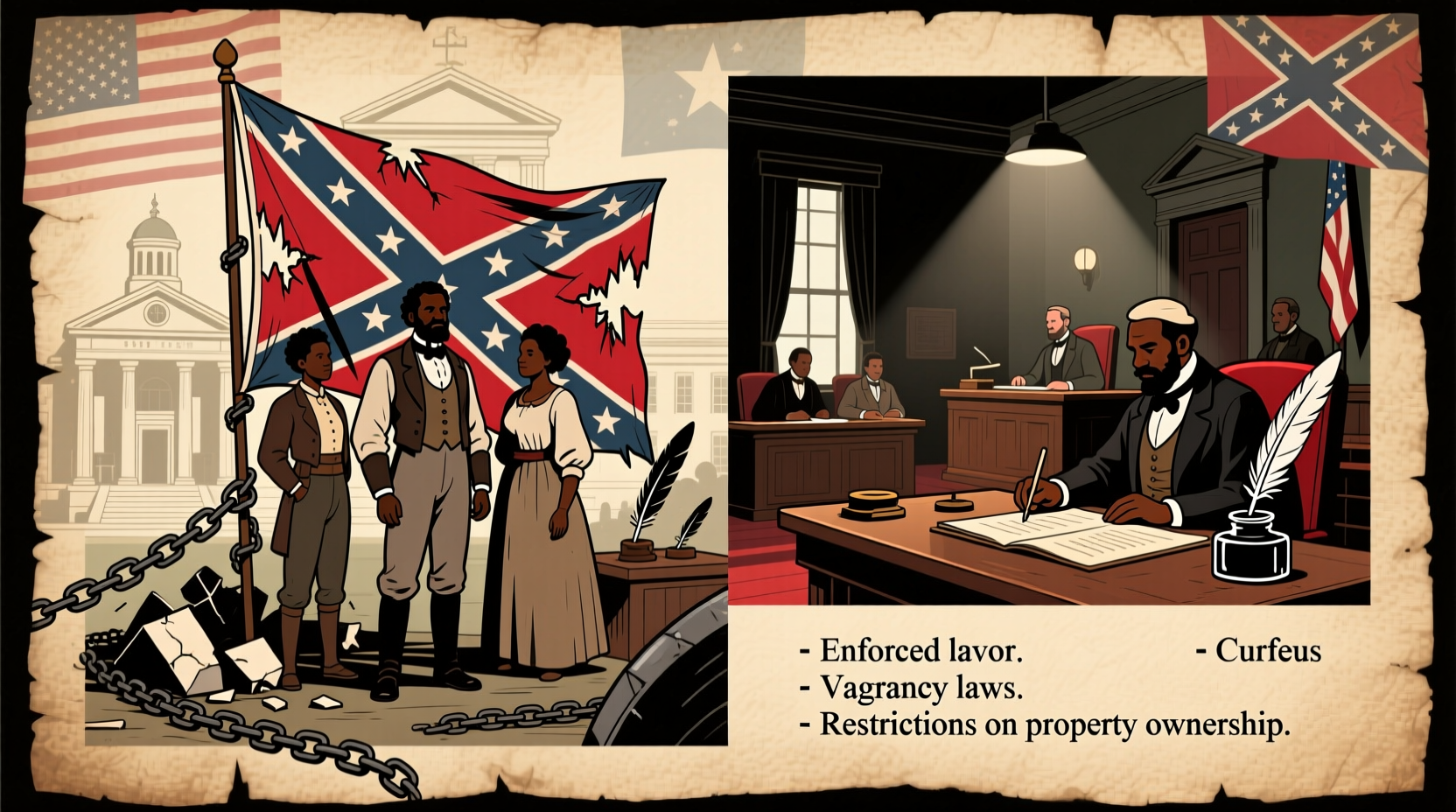

Enter the Black Codes. Enacted primarily between 1865 and 1866 by Southern state legislatures, these laws varied by region but shared a common goal: to limit Black autonomy and ensure a compliant workforce. Mississippi passed one of the first such codes in late 1865, quickly followed by Alabama, South Carolina, Louisiana, and others. Though framed as efforts to restore order, the Black Codes effectively reestablished many conditions of servitude under a new legal guise.

The Purpose Behind the Black Codes

The primary purpose of the Black Codes was threefold: economic control, social subordination, and political suppression.

- Economic Control: Southern economies depended on agriculture, which required large-scale labor. The Black Codes imposed vagrancy laws that criminalized unemployment. If a Black person could not prove employment, they could be arrested and \"leased out\" to private employers—often former slaveholders—through convict leasing systems. This ensured a steady supply of low-cost labor.

- Social Subordination: The codes restricted where Black people could live, travel, or own property. Some states barred them from renting land outside cities or prohibited them from testifying against white individuals in court. These measures reinforced white supremacy and prevented upward mobility.

- Political Suppression: By limiting education, gun ownership, and assembly rights, the codes curtailed Black civic participation. Even before Jim Crow laws formalized segregation, the Black Codes laid the groundwork for disenfranchisement.

“Freedom is not given; it is claimed. But in 1865, the South responded to Black freedom with laws designed to re-enslave in all but name.” — Dr. Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Historian of African American Studies, Harvard University

Key Provisions of the Black Codes: A Comparative Overview

The specifics of the Black Codes differed across states, but several recurring themes illustrate their intent. The table below outlines major provisions enacted in select Southern states.

| State | Vagrancy Laws | Labor Contracts | Restrictions on Movement | Court Testimony |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | Unemployed Black adults could be arrested and fined; failure to pay led to forced labor. | One-year contracts required; breaking contract resulted in arrest and unpaid labor. | Could not leave employer without written permission. | Prohibited from testifying in cases involving white people. |

| South Carolina | Idle Black persons deemed vagrants; subject to fines or labor. | All working-age Black people required annual labor contracts. | Curfews and travel restrictions imposed. | No testimony allowed against whites. |

| Louisiana | Broad definition of vagrancy included loitering or lack of visible employment. | Employers could reclaim runaway workers as if they were property. | Movement monitored; passes often required. | Limited legal standing in disputes with whites. |

This systemic framework effectively criminalized Black existence while shielding white authority from accountability. The message was clear: freedom would not disrupt the existing social order.

Resistance and Federal Response

The severity of the Black Codes provoked outrage among Northerners, abolitionists, and Radical Republicans in Congress. Reports of mass arrests, forced labor, and violent intimidation undermined claims that the South had accepted emancipation. In response, Congress refused to seat representatives from Southern states until they ratified the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the law.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 directly challenged the Black Codes by affirming that all persons born in the U.S. (excluding Native Americans) were citizens with equal rights to make contracts, sue, and own property. Coupled with the 14th and later the 15th Amendments, federal intervention temporarily curtailed the most overt forms of racial discrimination.

Legacy and Long-Term Impact

Although the Black Codes were officially invalidated during Radical Reconstruction, their influence persisted. After federal troops withdrew in 1877, Southern states replaced them with Jim Crow laws, which institutionalized segregation and voter suppression. The carceral logic of the Black Codes—criminalizing poverty and mobility—resurfaced in 20th-century policing practices and mass incarceration.

Historians now recognize the Black Codes as a foundational element in the development of systemic racism in America. They represent an early example of how legal frameworks can be weaponized to undermine constitutional rights under the pretense of public order.

Mini Case Study: The Case of Henry Adams

Henry Adams, a formerly enslaved man from Louisiana, testified before Congress in 1880 about his experiences after emancipation. He described how Black men were routinely arrested on vague charges like “vagrancy” or “insulting gestures,” then forced into labor camps. “We are worse off now than under slavery,” he stated, “because now we are enslaved by law.” His account exemplifies how the Black Codes transformed legal systems into tools of racial oppression, even as the nation proclaimed liberty.

Actionable Steps to Understand and Confront Historical Injustice

Understanding the origins and purpose of the Black Codes is not merely an academic exercise—it’s essential for recognizing patterns of inequality today. Consider the following checklist to deepen your awareness:

- Read primary sources such as the actual text of Mississippi’s 1865 Black Code statutes.

- Compare post-Civil War Southern laws with modern policies affecting marginalized communities.

- Explore how convict leasing evolved into today’s prison-industrial complex.

- Support educational initiatives that teach accurate Reconstruction history in schools.

- Advocate for policy reforms rooted in historical justice, such as sentencing equity and voting rights restoration.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were the Black Codes the same as Jim Crow laws?

No, though they served similar purposes. The Black Codes were enacted immediately after the Civil War (1865–1866) to restrict Black freedom, while Jim Crow laws emerged in the late 19th century after Reconstruction ended. Jim Crow formalized racial segregation in public spaces and lasted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. The Black Codes laid the ideological and legal foundation for Jim Crow.

Did any Northern states have Black Codes?

Yes, some Northern states had discriminatory laws prior to the Civil War, particularly regarding voting, education, and residency. However, these were generally less systematic and not tied to a plantation economy. Post-war, the term “Black Codes” specifically refers to Southern legislation designed to replace slavery with controlled labor and social subjugation.

How did the Black Codes affect families?

The codes disrupted family stability by forcing adults into long-term labor contracts away from home, restricting movement, and enabling state custody of Black children labeled “vagrant.” Some states allowed orphaned or unemployed Black youth to be apprenticed to white employers—often former slaveholders—without parental consent.

Conclusion: Learning from the Past to Shape a Just Future

The creation of the Black Codes was not an anomaly—it was a calculated response to the threat of racial equality. Their origins lie in economic dependency, white supremacy, and resistance to federal reform. Their purpose was to preserve a social order built on exploitation. Recognizing this history is crucial for understanding the deep roots of racial injustice in American institutions.

Knowledge is the first step toward change. By confronting the realities of Reconstruction—and the backlash that followed—we honor the resilience of those who fought for true freedom. Share this information, discuss it in classrooms and communities, and support efforts to teach inclusive history. Only by remembering the past can we build a more equitable future.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?