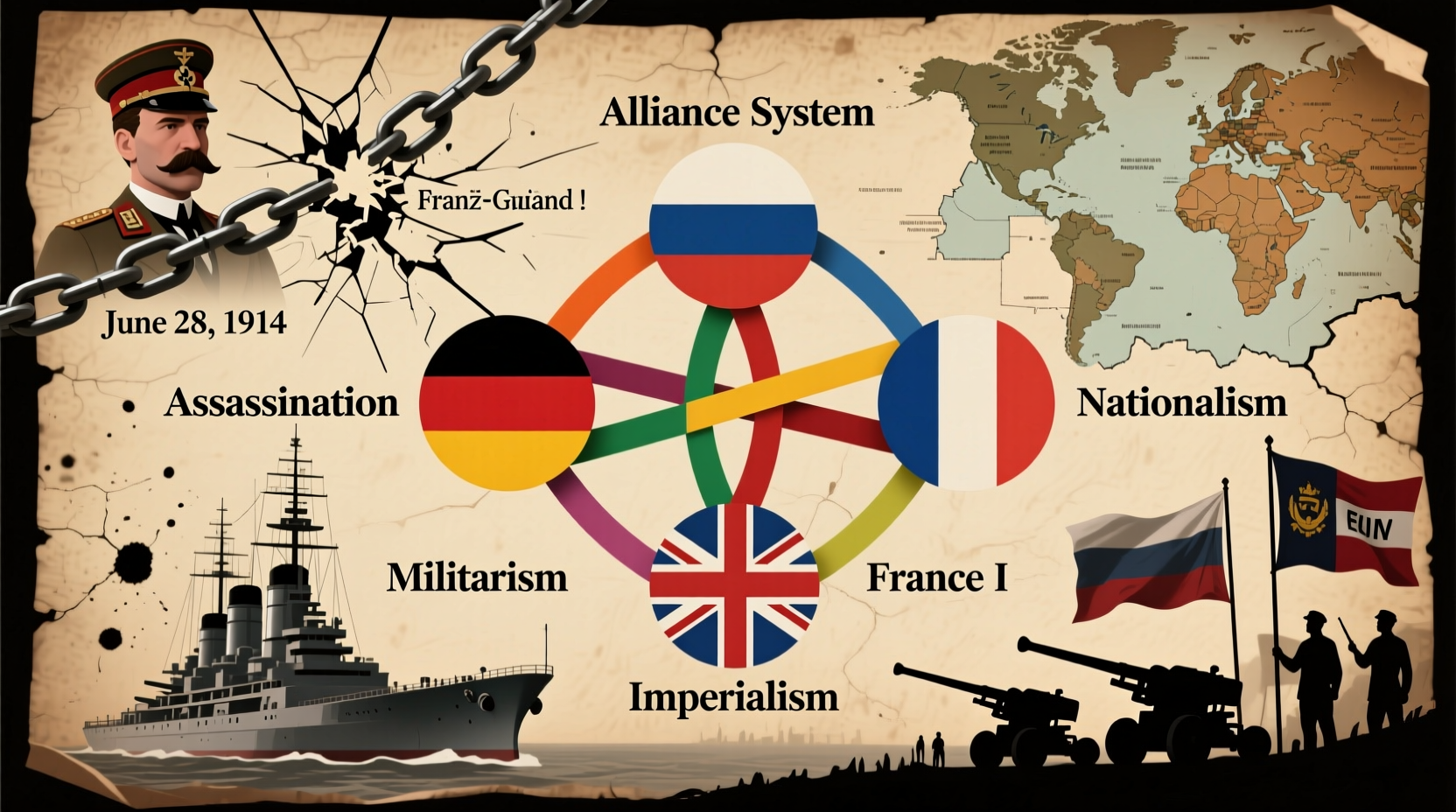

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a turning point in global history, drawing nations into a devastating conflict that reshaped borders, governments, and societies. While the immediate trigger was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the war’s roots ran far deeper. A complex web of political tensions, military strategies, imperial ambitions, and rigid alliance systems created an environment where a single act could ignite a continent-wide war. Understanding the key causes and contributing factors is essential to grasp how peace unraveled so rapidly.

The Alliance System: Europe’s Powder Keg

By the early 20th century, Europe was divided into two major alliance blocs: the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance. These agreements were intended as deterrents to war but ultimately acted as accelerants when conflict arose.

- Triple Alliance (1882): Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy.

- Triple Entente (1907): France, Russia, and the United Kingdom.

These alliances meant that any localized conflict risked dragging multiple powers into war. When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Russia mobilized in support of its Slavic ally, prompting Germany to declare war on Russia and then France. Britain entered after Germany violated Belgian neutrality—each step dictated by prior commitments.

Militarism and the Arms Race

In the decades before 1914, European powers engaged in aggressive military buildup. This militarism wasn’t just about defense—it reflected national pride, imperial competition, and a belief in the inevitability of war.

Germany expanded its navy to challenge British naval supremacy under Admiral Tirpitz’s \"Risk Theory,\" which held that a strong German fleet would deter Britain from entering any continental conflict. In response, Britain launched more advanced dreadnought-class battleships, fueling a naval arms race.

On land, conscription and large standing armies became the norm. Germany’s Schlieffen Plan—a detailed strategy for a two-front war—assumed rapid mobilization was critical. Once set in motion, these plans left little room for diplomacy. Mobilization schedules were so intricate that delays could mean defeat, creating pressure to act swiftly—even recklessly.

“Mobilization is not a measure of war, but war itself.” — Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, Chief of the German General Staff

Imperial Rivalries and Nationalism

Colonial competition intensified tensions among European powers. France and Germany clashed over Morocco in 1905 and 1911 (the Moroccan Crises), bringing Europe to the brink of war twice before 1914. Britain and Russia had longstanding rivalries in Central Asia—the so-called \"Great Game.\"

But nationalism also stirred unrest within empires. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a patchwork of ethnic groups—Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Romanians, and South Slavs—many of whom sought independence. Pan-Slavism, the idea that all Slavic peoples should unite, gained traction with Russian support and inspired nationalist movements in the Balkans.

Serbia, having recently gained full independence, saw itself as the leader of South Slavic unity. This threatened Austria-Hungary’s control over its Slavic populations, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had annexed in 1908. That annexation sparked outrage in Serbia and set the stage for future conflict.

The Balkans: Europe’s Tinderbox

The Balkan Peninsula was the most volatile region in Europe. Weak Ottoman control gave way to rising nation-states like Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, and Serbia. The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 redrew borders and displaced populations, leaving unresolved grievances.

Austria-Hungary viewed Serbia’s growing power and nationalist agitation as existential threats. Meanwhile, Russia saw itself as protector of the Slavs, making any conflict in the Balkans a potential flashpoint for great-power war.

The Spark: Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, visited Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. The date was symbolic—it marked the anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, a key moment in Serbian national identity.

Members of Young Bosnia, a nationalist group supported by the Serbian secret society known as the Black Hand, plotted to assassinate him. After a failed bomb attempt earlier in the day, the Archduke’s motorcade took a wrong turn and stalled near Gavrilo Princip, who seized the moment and shot both Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie.

This act transformed simmering tensions into open crisis. Austria-Hungary, backed by Germany, issued a harsh ultimatum to Serbia on July 23, demanding suppression of anti-Austrian activities and allowing Austrian officials to participate in investigations. Serbia accepted most terms but rejected foreign involvement in its judiciary.

Austria-Hungary declared war on July 28. Within days, the alliance system activated: Russia mobilized, Germany declared war on Russia (August 1) and France (August 3), and invaded Belgium. Britain declared war on Germany on August 4 after Germany refused to withdraw from neutral Belgium.

Timeline of Escalation (June–August 1914)

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| June 28, 1914 | Archduke Franz Ferdinand assassinated in Sarajevo |

| July 23 | Austria-Hungary issues ultimatum to Serbia |

| July 28 | Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia |

| July 30 | Russia begins general mobilization |

| August 1 | Germany declares war on Russia |

| August 3 | Germany declares war on France |

| August 4 | Germany invades Belgium; Britain declares war on Germany |

Contributing Factors Beyond the Obvious

While alliances, militarism, imperialism, and nationalism are often summarized as the “MAIN” causes of WWI, other structural and cultural factors played crucial roles:

- Lack of Crisis Diplomacy Mechanisms: Unlike today’s diplomatic channels (e.g., hotlines or multilateral forums), 1914 leaders had no formal means to de-escalate fast-moving crises.

- Public Opinion and Press: Nationalist newspapers stoked public fervor, making leaders reluctant to appear weak through compromise.

- Military Determinism: Many generals believed offensive action and speed were decisive. Plans like the Schlieffen Plan prioritized momentum over flexibility.

- Leadership Miscalculation: German leaders thought Britain might stay neutral. Austria-Hungary underestimated Serbia’s resolve and Russia’s willingness to intervene.

“The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.” — Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary, August 1914

Frequently Asked Questions

Could World War I have been avoided?

Yes, though it would have required stronger diplomacy, restraint from Austria-Hungary and Germany, and perhaps a less rigid mobilization system. Had the July Crisis been managed with cooler heads—such as through international mediation—the war might have been contained or delayed.

Why did the U.S. enter World War I later?

The United States remained neutral until 1917. It entered the war after Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare (sinking civilian ships like the Lusitania) and the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram, in which Germany proposed a military alliance with Mexico against the U.S.

Was the assassination the real cause of the war?

No—it was the catalyst. The underlying causes were decades in the making. Without the alliance system, militarism, and imperial tensions, the assassination might have led to a regional conflict rather than a world war.

Checklist: Key Causes of World War I

- ✅ Alliance System: Mutual defense pacts turned local war into global conflict.

- ✅ Militarism: Arms races and rigid war plans reduced diplomatic flexibility.

- ✅ Imperialism: Colonial competition fueled distrust among great powers.

- ✅ Nationalism: Ethnic aspirations destabilized empires, especially in the Balkans.

- ✅ Assassination of 1914: Triggered the final chain of events leading to war.

- ✅ Diplomatic Failure: No effective mechanism existed to halt escalation.

Conclusion: Learning from History

The origins of World War I reveal how interconnected systems—political, military, and social—can amplify a single event into catastrophe. It wasn’t fate, but a series of choices, miscalculations, and structural flaws that led millions into war.

Understanding these causes isn’t just academic; it offers lessons for managing international tensions today. Alliances must allow for dialogue. Military planning must include off-ramps. Nationalism must be balanced with cooperation. And above all, leaders must recognize that once mobilization begins, options shrink rapidly.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?