Evolution Of Windows Operating System

1/3

1/3

1/3

1/3

0

0

1/1

1/1

0

0

1/3

1/3

1/2

1/2

0

0

1/3

1/3

1/3

1/3

1/3

1/3

0

0

0

0

1/6

1/6

1/2

1/2

0

0

0

0

0

0

1/3

1/3

About evolution of windows operating system

Evolution of Windows Operating System: A Historical Overview

The Windows operating system has undergone significant transformation since its inception in 1985, evolving from a simple graphical user interface (GUI) for MS-DOS into a comprehensive, enterprise-grade computing platform. Microsoft introduced Windows 1.0 as a 16-bit GUI shell to compete with Apple’s Macintosh, offering basic multitasking and window management. Subsequent versions—Windows 2.0 and 3.x—improved graphics support and memory handling, enabling broader adoption in business environments.

With the release of Windows 95, Microsoft transitioned to a fully integrated 32-bit hybrid kernel, introducing Plug and Play hardware detection, preemptive multitasking, and the iconic Start menu. This marked a pivotal shift toward consumer-friendly design and widespread PC standardization. The follow-up releases—Windows 98 and ME—enhanced multimedia capabilities and internet integration but retained dependencies on DOS, limiting system stability.

A foundational architectural overhaul came with Windows XP in 2001, built on the Windows NT kernel. It unified consumer and professional lineups, delivering improved reliability, security through user account control, and extended hardware compatibility. XP achieved unprecedented market penetration, remaining in use across enterprises well beyond its end-of-life due to interface familiarity and software compatibility.

Windows Vista (2007) and Windows 7 (2009) further refined the NT architecture, introducing the Aero glass interface, enhanced search indexing, and DirectX 10/11 support. While Vista faced criticism over performance demands and driver incompatibility, Windows 7 optimized resource usage, becoming one of the most widely deployed OS versions globally. Its lifecycle concluded in January 2020, coinciding with Microsoft's push toward cloud-integrated ecosystems.

Architectural Advancements and Enterprise Integration

Windows 8 (2012) represented a radical redesign focused on touch-first interfaces, replacing the traditional Start menu with a full-screen tile layout. Despite innovations such as UEFI secure boot and native USB 3.0 support, the interface alienated desktop users. However, it laid groundwork for cross-device compatibility, particularly with tablets and hybrid devices.

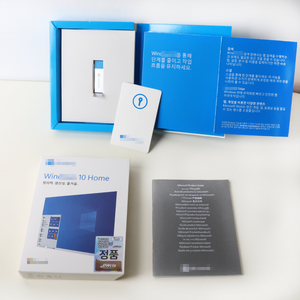

Responding to feedback, Windows 10 (2015) restored the Start menu while retaining touch optimization, establishing a "universal app" model across PCs, smartphones, and Xbox consoles. It introduced Cortana, virtual desktops, and Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), catering to developers and IT administrators. From a deployment perspective, Microsoft shifted to a continuous servicing model—delivering feature updates biannually and security patches monthly—enabling faster vulnerability mitigation and standardized enterprise rollouts.

Security enhancements became central to development priorities, including Device Guard, Credential Guard, BitLocker encryption, and Secure Boot. Hardware requirements evolved accordingly, mandating Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0 chips and UEFI firmware for modern deployments. These measures aligned with Zero Trust frameworks adopted by large organizations.

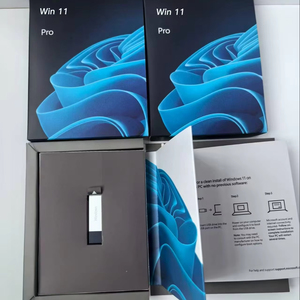

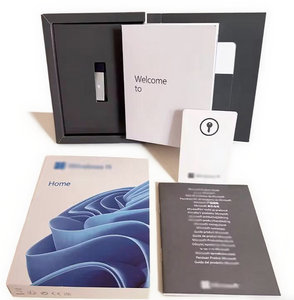

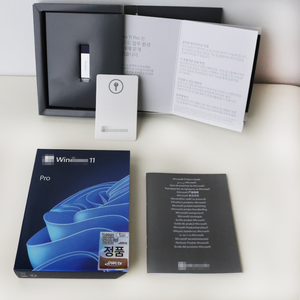

Windows 11 (2021) reinforced these trends with a centered taskbar, redesigned UI using Fluent Design, and stricter hardware prerequisites—including TPM 2.0 and Secure Boot enabled by default. It also expanded WSL capabilities, integrated Android apps via Amazon Appstore, and prioritized Teams communication within the OS shell. The focus remains on seamless cloud connectivity through OneDrive, Azure Active Directory, and Microsoft 365 integration.

Market Impact and Deployment Trends

As of 2024, Windows maintains over 70% global desktop OS market share according to StatCounter, driven primarily by corporate adoption of Windows 10 and gradual migration to Windows 11. Enterprises benefit from long-term servicing channels (LTSC), which provide stable builds without feature disruptions for critical infrastructure.

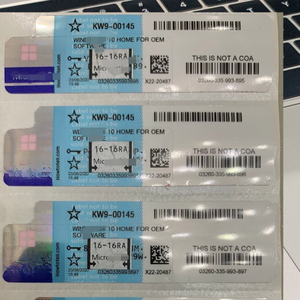

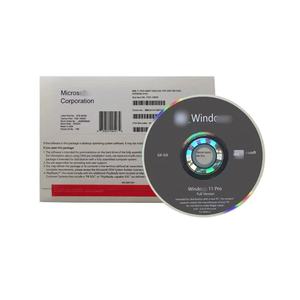

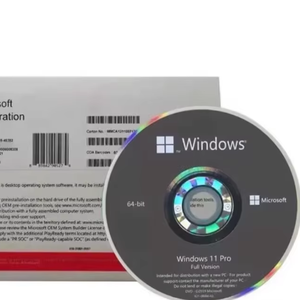

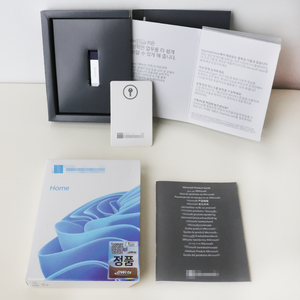

Microsoft’s licensing model has also evolved—from perpetual OEM licenses to subscription-based offerings tied to Microsoft 365. This supports ongoing revenue streams and encourages regular upgrades. Volume licensing programs like Open Value and Enterprise Agreements offer centralized management, audit compliance, and downgrade rights for legacy systems.

Deployment scalability is facilitated through tools such as Windows Autopilot, Microsoft Endpoint Configuration Manager (MECM), and Intune for cloud-first device provisioning. These enable zero-touch installations across thousands of endpoints, reducing IT overhead and ensuring configuration consistency.

FAQs

What are the key differences between Windows NT and earlier versions?

Windows NT introduced a fully 32-bit microkernel architecture independent of MS-DOS, providing true multitasking, memory protection, and multi-user capabilities. Earlier versions relied on DOS for core operations, making them less stable and secure compared to the modular, hardware-abstracted NT design.

How has Microsoft handled backward compatibility?

Multilayered compatibility layers—including NTVDM, WoW64, and Application Compatibility Toolkit (ACT)—allow execution of 16-bit and 32-bit applications on 64-bit systems. However, support for legacy components diminishes with each major version; Windows 11 no longer supports 32-bit processors or certain deprecated APIs.

What are the minimum hardware requirements for Windows 11?

Windows 11 requires a 1 GHz or faster 64-bit processor with two or more cores, 4 GB RAM, 64 GB storage, UEFI firmware with Secure Boot capability, TPM 2.0, and DirectX 12-compatible GPU with WDDM 2.0 driver. Devices must pass Microsoft’s PC Health Check validation for official support.

Can organizations defer feature updates?

Yes, enterprise editions allow deferral of feature updates up to 365 days and security updates up to 30 days via Group Policy or MDM solutions. LTSC editions receive only security patches for 5–10 years, ideal for specialized systems requiring operational continuity.

Is Windows moving toward an open-source model?

While the core OS remains proprietary, Microsoft has embraced open-source collaboration through projects like WSL, .NET runtime, and PowerShell. The company contributes to Linux kernel development and hosts numerous repositories on GitHub, reflecting a strategic pivot toward interoperability and developer engagement.