When governments increase spending—on infrastructure, education, or public health—the ripple effects can be far greater than the initial outlay. This amplification is captured by a key concept in macroeconomics: the spending multiplier. Understanding how this works allows policymakers, analysts, and informed citizens to gauge the true impact of fiscal decisions on national income and employment.

The spending multiplier reveals how an initial change in government or private spending triggers successive rounds of consumption, ultimately leading to a larger total increase in economic output. While rooted in theory, its applications are deeply practical—from evaluating stimulus packages during recessions to forecasting growth trajectories.

What Is the Spending Multiplier?

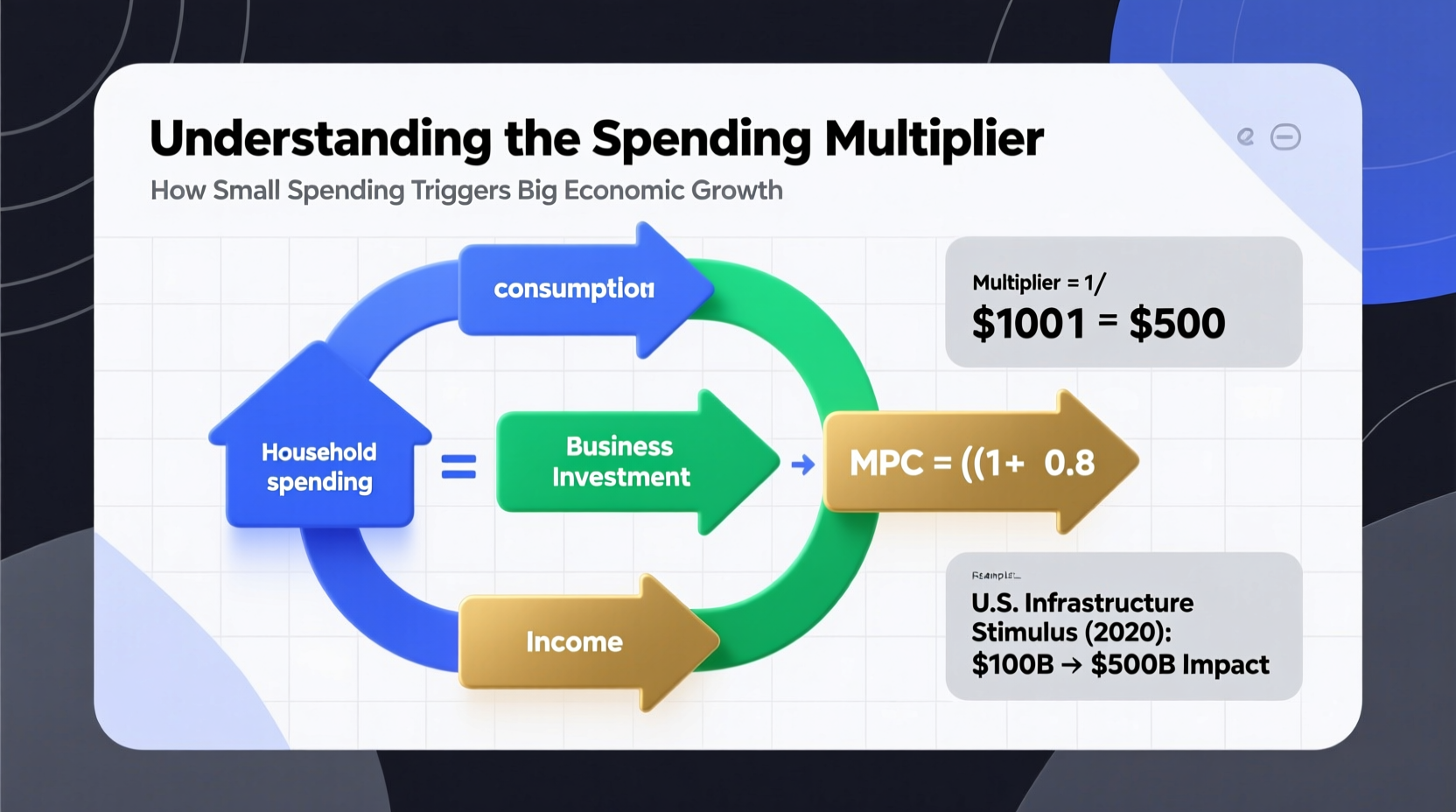

In simple terms, the spending multiplier measures how much total GDP increases for every dollar of new spending injected into the economy. If the government spends $1 billion on road construction, that money doesn’t vanish after wages are paid. Workers spend part of their income, businesses earn more revenue, hire additional staff, and the cycle continues. Each round adds to aggregate demand.

The size of the multiplier depends on how much of each new dollar of income people choose to spend rather than save. The higher the propensity to consume, the larger the multiplier effect.

“Fiscal multipliers are not just theoretical constructs—they shape real-world decisions about when and how aggressively to stimulate economies.” — Olivier Blanchard, Former Chief Economist at the IMF

Breaking Down the Formula

The most basic form of the spending multiplier is derived from Keynesian economics and assumes a closed economy with no taxes:

Spending Multiplier = 1 / (1 – MPC)

- MPC = Marginal Propensity to Consume (the fraction of additional income spent)

- MPS = Marginal Propensity to Save (the fraction saved), where MPC + MPS = 1

For example, if consumers spend 80 cents of every extra dollar they earn, then MPC = 0.8, and the multiplier becomes:

1 / (1 – 0.8) = 1 / 0.2 = 5

This means that a $10 billion increase in government spending could lead to a $50 billion rise in GDP over time, assuming full utilization of resources and no offsetting factors like crowding out.

Step-by-Step: Calculating the Spending Multiplier

Follow this sequence to compute the spending multiplier accurately under different assumptions:

- Determine the MPC: Use household survey data or historical consumption patterns. For instance, if disposable income rises by $1,000 and consumption increases by $750, MPC = 0.75.

- Select the appropriate formula:

- Basic model: Multiplier = 1 / (1 – MPC)

- With taxes: Multiplier = 1 / (1 – MPC(1 – t)), where t = tax rate

- Open economy: Multiplier = 1 / (MPS + MPM + MPT), including marginal propensities to import and pay taxes

- Plug in values. Example: MPC = 0.75, tax rate = 20% → (1–t) = 0.8 → MPC(1–t) = 0.6 → Multiplier = 1 / (1 – 0.6) = 2.5

- Multiply by initial spending change. A $20 billion infrastructure boost would generate $50 billion in GDP growth (20 × 2.5).

- Adjust for real-world constraints: Consider slack in the economy, interest rate responses, and inflationary pressures.

Real-World Application: The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009)

During the Great Recession, the U.S. government passed a $787 billion stimulus package aimed at jumpstarting economic activity. Economists used multiplier models to estimate its impact.

According to research by Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi, components of the stimulus had varying multipliers:

| Type of Spending | Estimated Multiplier | Reason for Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Unemployment benefits | 1.64 | High MPC among recipients; immediate spending |

| Infrastructure investment | 1.57 | Direct job creation and long-term productivity gains |

| Tax cuts for lower/middle-income households | 1.19 | Higher likelihood of spending vs. saving |

| Tax cuts for high-income earners | 0.34 | Lower MPC; more likely to save or invest abroad |

This case illustrates a crucial point: not all spending has equal multiplier power. Targeting groups with high marginal propensities to consume enhances overall effectiveness.

Factors That Influence the Size of the Multiplier

The theoretical multiplier rarely matches reality exactly. Several conditions affect its magnitude:

- Economic slack: In recessions, idle workers and factories mean new spending faces little inflation resistance, boosting the multiplier.

- Crowding out: If government borrowing raises interest rates, it may reduce private investment, weakening the net effect.

- Openness of the economy: In nations with high import dependence, some increased demand leaks abroad, reducing domestic impact.

- Monetary policy response: Accommodative central banks (e.g., holding rates steady) enhance fiscal multipliers.

- Expectations: If households believe tax cuts are temporary, they may save rather than spend, dampening the effect.

Checklist: Evaluating Fiscal Policies Using the Spending Multiplier

Use this checklist when analyzing proposed government spending or tax changes:

- ✅ Identify the target group: Will funds reach those with high MPC?

- ✅ Assess current economic conditions: Is there significant unemployment or unused capacity?

- ✅ Estimate leakages: How much will be saved, taxed away, or spent on imports?

- ✅ Consider timing: Fast-disbursing programs (like direct transfers) act quicker than multi-year projects.

- ✅ Review financing method: Debt-financed spending typically has higher short-run impact than tax-funded measures.

- ✅ Monitor secondary effects: Could rising demand trigger inflation or currency appreciation?

Frequently Asked Questions

Can the spending multiplier be less than 1?

Yes. In economies near full capacity, new government spending may displace private activity (crowding out), resulting in a net gain below the initial injection. Some studies find multipliers as low as 0.5 in expansions.

Why do tax cuts sometimes have smaller multipliers than direct spending?

Tax reductions give people discretion over whether to spend or save. If confidence is low or debt levels are high, households may prioritize saving, especially among wealthier individuals. Direct spending, such as building schools or hiring teachers, immediately enters the economy.

Does the multiplier work in reverse during austerity?

Yes. Cutting government spending can reduce GDP by a multiple of the cut. Research following the 2010 European austerity measures showed sharper-than-expected contractions, consistent with multiplier effects working in reverse.

Conclusion: Turning Theory Into Insight

The spending multiplier is more than a textbook equation—it’s a lens for understanding how financial flows move through an economy. Whether you're assessing policy proposals, writing reports, or simply staying informed, mastering this tool equips you to see beyond headline numbers and grasp deeper economic dynamics.

Next time you hear about a new infrastructure bill or tax reform, ask: Who receives the money? How much will they spend? What are the broader economic conditions? These questions bring the multiplier to life—and reveal the hidden leverage behind smart fiscal design.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?