Creatine is one of the most researched and effective supplements in sports nutrition. Known for boosting strength, power output, and muscle mass, it’s a staple in many fitness regimens. But with multiple forms on the market—most notably creatine monohydrate and creatine hydrochloride (HCl)—consumers face a dilemma: does paying more for creatine HCl actually deliver better results, especially when it comes to reducing bloating?

This article breaks down the differences between creatine monohydrate and creatine HCl, focusing on absorption, dosage, cost, and gastrointestinal side effects like bloating. We’ll examine clinical evidence, real-world usage, and expert insights to determine whether the premium price tag of HCl is justified—or if you’re better off sticking with the classic, budget-friendly monohydrate.

Understanding Creatine: Why It Works

Creatine is a naturally occurring compound found in muscle cells that helps produce energy during high-intensity exercise. Supplementing increases phosphocreatine stores in muscles, enabling faster ATP regeneration—the primary energy currency of cells during short bursts of effort like sprinting or lifting weights.

The benefits are well-documented:

- Increase in lean muscle mass over time

- Improved strength and power output

- Enhanced recovery between sets

- Potential cognitive benefits under sleep-deprived or stressful conditions

Despite its popularity, some users report side effects such as water retention, stomach discomfort, and bloating—especially during the loading phase. This has led to the development of alternative forms like creatine HCl, marketed as being more soluble, better absorbed, and less likely to cause bloating.

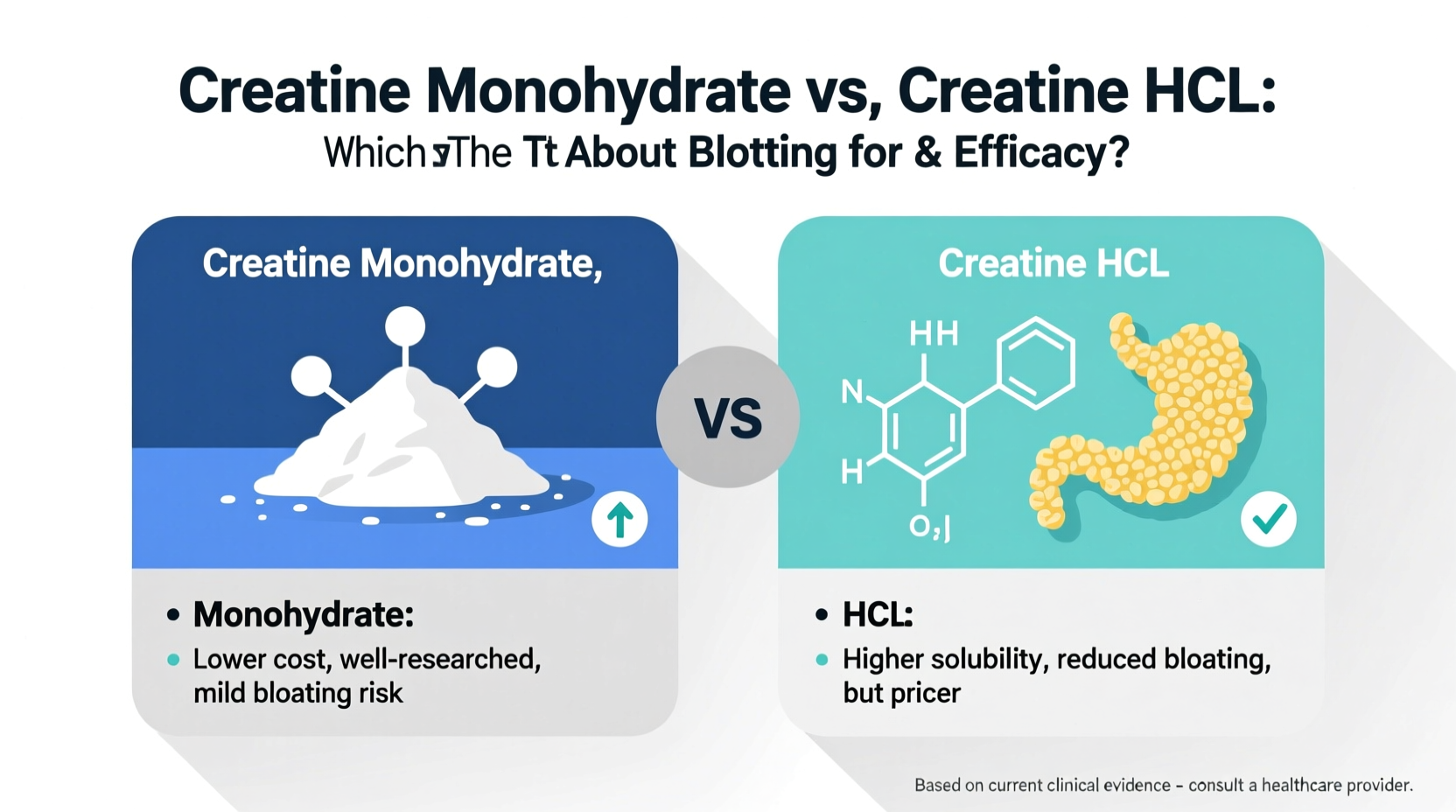

Comparing Creatine Monohydrate and Creatine HCl

At first glance, both compounds deliver creatine—but their chemical structure and solubility differ significantly.

Creatine Monohydrate

This is the original and most studied form of creatine. It consists of creatine bound to a water molecule. Over 95% of human research on creatine uses this form, confirming its safety and efficacy.

Typical dosing involves either a “loading phase” (20g per day for 5–7 days) followed by a maintenance dose (3–5g daily), or skipping the load and starting directly with 3–5g/day. Benefits usually appear within 2–4 weeks.

Creatine HCl (Hydrochloride)

Creatine HCl is creatine bonded to hydrochloric acid. Manufacturers claim this bond increases solubility and absorption, allowing for lower doses (often 750mg–1.5g daily) without needing a loading phase. Because of these claims, HCl is frequently marketed as causing less bloating and stomach upset than monohydrate.

However, despite aggressive marketing, independent research on creatine HCl remains limited compared to decades of data supporting monohydrate.

“Monohydrate remains the gold standard due to its proven track record. Alternative forms may offer theoretical advantages, but they lack the same depth of scientific validation.” — Dr. Abigail Collins, Sports Nutrition Researcher, University of Colorado

Does Creatine Cause Bloating? The Science Behind Water Retention

One of the most common concerns about creatine is bloating. This typically stems from increased intracellular water retention in muscle tissue—a normal physiological response, not fat gain or puffiness.

When creatine enters muscle cells, it draws water with it osmotically. This can lead to a slight increase in body weight (usually 1–3 pounds in the first week) and a feeling of fullness or tightness in the abdomen for some users.

Importantly, this water is stored *inside* the muscle cells (intracellular), which supports cell volumization and anabolic signaling—beneficial for growth. It is not subcutaneous or visceral bloating, which would indicate digestive distress or fluid imbalance.

Is HCl Really Better for Avoiding Bloating?

Proponents of creatine HCl argue that because it's more soluble and requires smaller doses, it doesn’t overwhelm the digestive system or pull excess water into the gut. While plausible in theory, there is minimal peer-reviewed evidence to support this.

A 2014 study published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition compared creatine HCl to monohydrate and found no significant difference in perceived gastrointestinal discomfort at equivalent doses. Another review concluded that while HCl shows higher solubility *in vitro*, this hasn't consistently translated into superior absorption or fewer side effects in humans.

Performance, Absorption, and Dosage Comparison

To evaluate whether HCl is worth the extra cost, we need to compare key factors: absorption efficiency, required dosage, and performance outcomes.

| Factor | Creatine Monohydrate | Creatine HCl |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility in Water | Moderate (~1g dissolves in 60mL water) | High (~1g dissolves in 6mL water) |

| Standard Daily Dose | 3–5 grams | 0.75–1.5 grams |

| Loading Phase Required? | Optional (speeds saturation) | Not typically used |

| Time to Saturate Muscles | ~7 days with loading; ~28 days without | Claimed faster, but unverified in studies |

| Scientific Backing | Over 500+ studies | Few independent trials |

| Cost per Month (Approx.) | $8–$15 | $30–$60 |

| Gastrointestinal Tolerance | Generally good; mild bloating possible | Marketed as better, but evidence lacking |

The higher solubility of HCl is undeniable in lab settings. However, solubility does not automatically equate to better absorption or reduced side effects. The human digestive system is complex, and just because a compound dissolves easily doesn’t mean it performs better once ingested.

Moreover, creatine monohydrate already has high bioavailability—about 95% of ingested creatine reaches the bloodstream when taken correctly. There’s little room for improvement, making the claimed advantages of HCl marginal at best.

Real-World Experience: A Mini Case Study

Consider Mark, a 32-year-old recreational lifter who started using creatine to improve his gym performance. He initially chose creatine HCl after reading online reviews claiming it was “gentler on the stomach” and wouldn’t cause water retention.

After four weeks at 1g per day, he noticed no strength gains and still felt flat during workouts. Skeptical, he switched to micronized creatine monohydrate at 5g daily. Within 10 days, he experienced increased training volume, improved muscle fullness, and no notable bloating.

“I wasted nearly $50 on HCl thinking I was avoiding bloating,” Mark said. “But I wasn’t getting results. Once I switched, everything changed—and my stomach was fine.”

His experience reflects a broader trend: many users report similar outcomes, finding monohydrate effective and well-tolerated, while HCl fails to deliver noticeable benefits despite the higher price.

Cost Analysis: Is HCl Worth the Premium?

Let’s break down the numbers. A 500g container of creatine monohydrate costs around $12 and lasts approximately 100 days at 5g/day. That’s about $0.12 per serving.

In contrast, a 100g bottle of creatine HCl often sells for $35–$45. Even at a conservative 1g/day, it provides only 100 servings—costing $0.35 to $0.45 per dose. That’s nearly four times the price for a product with far less scientific backing.

Unless future research demonstrates clear superiority in absorption, muscle uptake, or tolerability, the economic argument strongly favors monohydrate.

How to Minimize Bloating—Regardless of Form

If bloating is your main concern, the choice between monohydrate and HCl may matter less than how you use the supplement. Here’s a step-by-step guide to reducing discomfort:

- Start with a low dose: Begin with 3g per day instead of jumping into a 20g loading phase.

- Take it with food: Consuming creatine with carbohydrates or a mixed meal enhances insulin release, which helps shuttle creatine into muscles and reduces free-floating concentrations in the gut.

- Stay hydrated: Drink plenty of water throughout the day. Dehydration can worsen perceived bloating.

- Split your dose: Take 1.5g in the morning and 1.5g post-workout to avoid overwhelming your system.

- Monitor symptoms: If bloating persists beyond 2–3 weeks, consider pausing and reassessing. True intolerance is rare but possible.

Additionally, avoid mixing creatine with high-fiber or gas-producing foods immediately before or after dosing, as this can exacerbate abdominal discomfort.

Checklist: Choosing the Right Creatine for You

- ✅ Prioritize third-party tested brands (look for NSF Certified for Sport or Informed Choice logos)

- ✅ Choose micronized creatine monohydrate for smooth mixing and fast dissolution

- ✅ Avoid proprietary blends that hide exact dosages

- ✅ Consider your budget—monohydrate offers unmatched value

- ✅ Consult a healthcare provider if you have kidney issues or take medications

Frequently Asked Questions

Can creatine HCl cause bloating?

Yes, although it’s less commonly reported, any form of creatine can contribute to water retention in muscle cells, which some users interpret as bloating. There is no conclusive evidence that HCl causes significantly less bloating than monohydrate in real-world use.

Do I need to load creatine HCl?

No, manufacturers typically recommend skipping the loading phase with HCl due to claims of higher absorption. However, since muscle saturation still depends on total creatine intake over time, consistent daily use is essential regardless of form.

Is creatine monohydrate outdated?

No. Despite newer forms entering the market, creatine monohydrate remains the most extensively studied, effective, and affordable option. It is not obsolete—it’s foundational.

Final Verdict: Stick With Science, Not Marketing

The idea that creatine HCl is superior because it’s more expensive or dissolves better is largely driven by marketing, not science. While it may offer slightly better solubility, this hasn’t been shown to translate into meaningful improvements in performance, absorption, or reduction in bloating for most people.

Creatine monohydrate continues to be the benchmark. It works, it’s safe, and it’s affordable. For those concerned about bloating, adjusting dosage timing, staying hydrated, and pairing it with food are more effective strategies than switching to a pricier alternative.

If new research emerges proving HCl’s clear superiority in head-to-head trials—particularly regarding long-term muscle uptake and gastrointestinal comfort—it may earn a place alongside monohydrate. Until then, the evidence overwhelmingly supports sticking with the original.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?