During World War I, millions of men went to war carrying a small, stamped metal disc around their necks. These simple objects—commonly known as dog tags—were not just military accessories; they were essential tools for identifying fallen soldiers in the chaos of trench warfare. With high casualty rates and often unrecognizable remains, accurate identification became a matter of dignity, record-keeping, and closure for families back home. Understanding what information was recorded on these tags, how it was formatted, and what each element signified offers a window into both military logistics and personal history.

The Purpose and Evolution of WWI Dog Tags

Prior to the 20th century, armies rarely issued standardized identification for soldiers. In the American Civil War, some troops pinned paper notes to their uniforms, but these were easily lost or destroyed. By the time of World War I, advances in warfare—and the devastating scale of casualties—demanded a more reliable system. The British, American, German, French, and other forces adopted metal identification tags, typically made from stamped steel or brass, designed to survive battlefield conditions.

These tags served three primary purposes: to identify the dead, to assist medical personnel in tracking wounded soldiers, and to maintain accurate military records. Unlike modern digital systems, WWI-era ID relied entirely on physical markings. As such, the format and content of dog tags varied significantly between nations, reflecting differing administrative practices and military structures.

Standard Features of Allied Dog Tags

The most widely studied examples come from the U.S. Army, which entered the war in 1917. The standard U.S. issue was an oval-shaped aluminum tag, later changed to monel metal (a corrosion-resistant alloy), with a notched end—popularly believed to ensure proper alignment in manual imprinting machines used for casualty reports.

A typical American WWI dog tag included the following information:

- Soldier’s full name

- Army serial number

- Unit designation (regiment and division)

- Religious preference (e.g., “P” for Protestant, “C” for Catholic, “H” for Hebrew)

- Date of tetanus vaccination

- Nationality (often “AMER” for American)

The duplication of tags—one to remain with the body and one to be sent to headquarters—was standard practice. This redundancy ensured that even if one tag was lost, the other could still provide vital data.

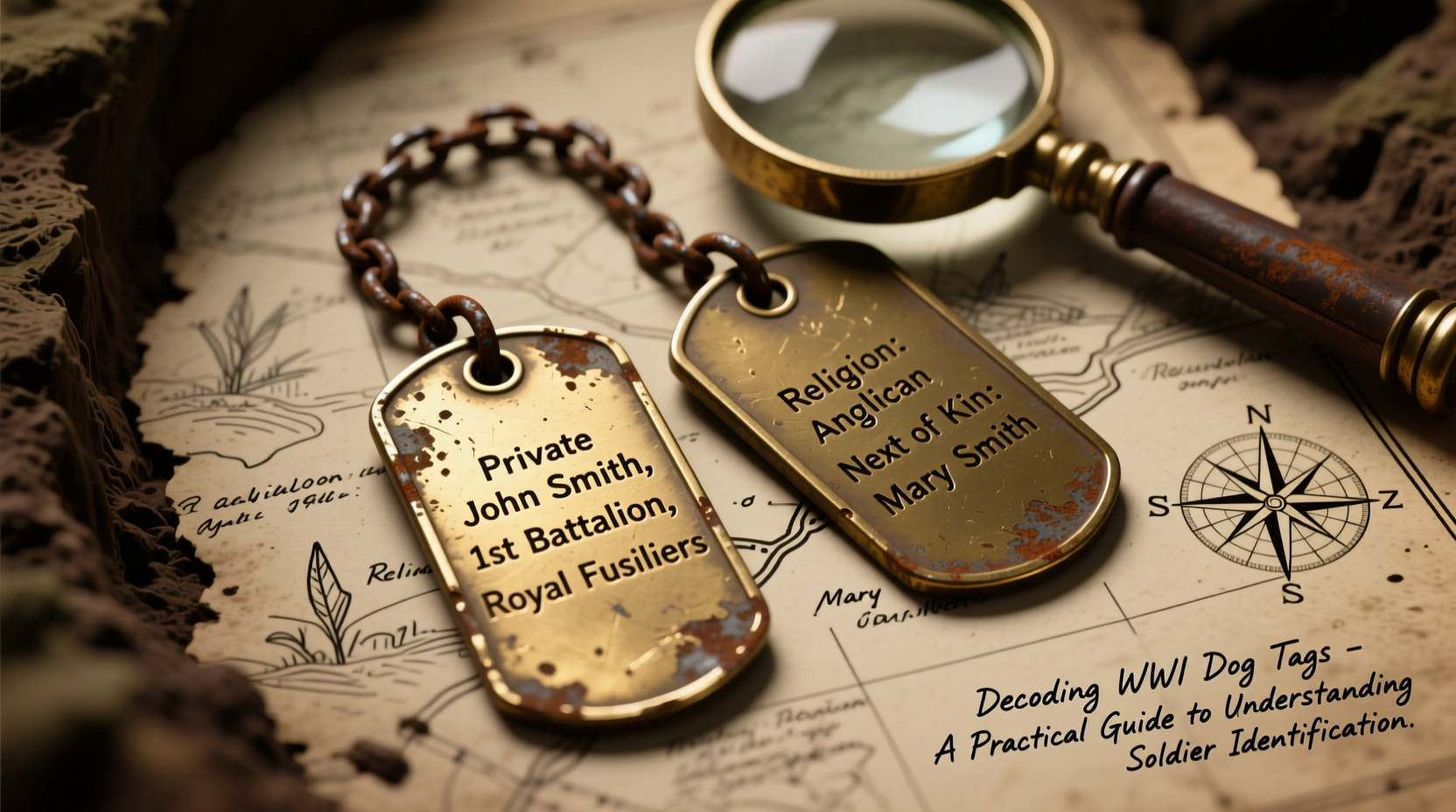

British and Commonwealth Tags

British forces used two rectangular discs made of compressed fiber or vulcanized asbestos fiber early in the war, later switching to metal. One tag stayed with the body, the other was returned to the War Office. Information typically included:

- Service number

- Name

- Regiment or corps

- Religious denomination

Notably, British tags did not include blood type or next of kin—information that would become standard in WWII.

Decoding the Markings: A Step-by-Step Guide

Interpreting a WWI dog tag requires attention to detail and context. Here’s a structured approach to extracting meaningful information:

- Determine the country of origin – Look for national abbreviations, language, or insignia. “U.S.” or “USA” indicates American issue; “G.R.” (Georgius Rex) suggests British service under King George.

- Identify the soldier’s name – Usually listed in full or last name followed by initials. Be mindful of common misspellings due to handwriting errors during enlistment.

- Analyze the service number – In the U.S. Army, numbers could indicate branch or draft status. For example, numbers starting with “1” often belonged to Regular Army enlistees, while higher ranges indicated National Guard or Draft registrants.

- Check unit information – Regiment, battalion, and division details help trace a soldier’s deployment history. The 1st Infantry Division, for instance, saw heavy action in France.

- Note medical data – Vaccination dates, particularly for tetanus, were crucial for medical staff treating wounded soldiers.

- Research religious designation – While seemingly minor, this detail was important for burial rites and family notification.

“Dog tags were the first line of dignity after death. They turned anonymous remains into named individuals deserving of recognition.” — Dr. Helen Prescott, Military Archivist at the Imperial War Museum

Common Misinterpretations and How to Avoid Them

Amateur collectors and genealogists often misread key elements on dog tags. Below is a comparison of frequent errors and correct interpretations:

| Misconception | Reality | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| The notch was for placing in the mouth of the dead | The notch aligned the tag in the Model 1918 Addressograph machine | Prevents mythologizing; supports historical accuracy |

| All tags had blood type | Blood typing was not routine until WWII | Helps date unidentified tags correctly |

| Serial number equals rank | Numbers reflected enlistment order, not hierarchy | Prevents confusion about military status |

| “P” stands for Protestant only | In some cases, “P” meant “No Preference” | Important for religious and cultural research |

Real Example: Interpreting a Recovered U.S. Tag

In 2018, a metal detectorist uncovered a corroded dog tag in the Argonne Forest, France. The tag read:

SMITH J.H. SERV NO: 1245678 32 INF DIV TET VACC: 15 MAR 17 REL: P NAT: AMER

Using archival records, researchers matched the serial number to James H. Smith, a private in the 128th Infantry Regiment, 32nd Division. His service records showed he was wounded in October 1918 during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and evacuated, suggesting the tag was lost—not left with a body. This case illustrates how dog tags, even when detached from remains, can contribute to reconstructing individual wartime experiences.

How to Preserve and Research a WWI Dog Tag

If you’ve inherited or discovered a WWI dog tag, preserving its integrity and uncovering its story is both a responsibility and an opportunity. Follow this checklist to proceed ethically and effectively:

- Handle the tag with clean cotton gloves to prevent oil transfer

- Store in a dry, acid-free container away from direct sunlight

- Photograph both sides clearly for documentation

- Search military databases like the National Archives (U.S.) or Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- Contact veteran organizations or historical societies for assistance

- Never attempt to clean aggressively—corrosion may obscure but also protect underlying text

Frequently Asked Questions

Did all countries use dog tags in WWI?

No, adoption was inconsistent. While the U.S., Britain, Germany, and France issued them widely, some smaller nations relied on cloth labels or no formal ID. Italy introduced metal tags late in the war, and Russia had limited distribution due to industrial constraints.

Can I find out if a soldier survived the war using only the dog tag?

Not definitively. The tag itself doesn’t indicate fate. However, cross-referencing the name and number with muster rolls, casualty lists, and pension records can reveal whether the soldier returned, was wounded, captured, or killed.

Were officers issued dog tags too?

Yes. Although officers sometimes carried personalized identification, they were required to wear standard-issue tags just like enlisted men. Their tags often included the same fields, though some nations added rank or commission date.

Conclusion: Honoring Identity Through Understanding

WWI dog tags are more than relics—they are intimate artifacts of identity forged in one of history’s most brutal conflicts. Each stamped letter and number represents a person who served, suffered, and in many cases, sacrificed. Decoding these tags is not merely an academic exercise; it’s an act of remembrance. Whether you’re a historian, collector, or descendant of a veteran, taking the time to understand what these tags say—and what they mean—connects us across time to the individuals behind the uniform.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?