Poor posture is a modern epidemic. Hours spent hunched over laptops, smartphones, and steering wheels have made slouching almost second nature. As awareness grows, so has the market for quick fixes—chief among them, posture correctors. These braces promise to pull your shoulders back, align your spine, and retrain your body into standing tall. But do they actually work? More importantly, could they be doing more harm than good by weakening the very muscles they’re supposed to help?

The truth is nuanced. Posture correctors can offer short-term relief and serve as a helpful reminder to sit up straight. However, relying on them long-term without addressing the root causes of poor posture may lead to muscle dependency and even atrophy. Understanding how these devices function—and when to use (or avoid) them—is essential for anyone serious about improving their posture sustainably.

How Posture Correctors Work: The Mechanics Behind the Brace

Posture correctors come in various forms—straps that wrap around the shoulders, vests with rigid supports, or wearable bands that vibrate when you slouch. Most operate on a simple principle: mechanical restriction. By pulling the shoulders back and limiting forward rounding of the upper back, they force the body into what appears to be a neutral spinal alignment.

This external support can feel immediately effective. Users often report feeling “taller” or “lighter” within minutes of wearing one. That sensation comes from realignment of the thoracic spine and scapulae, reducing pressure on nerves and soft tissues compressed by prolonged kyphosis (excessive forward curvature).

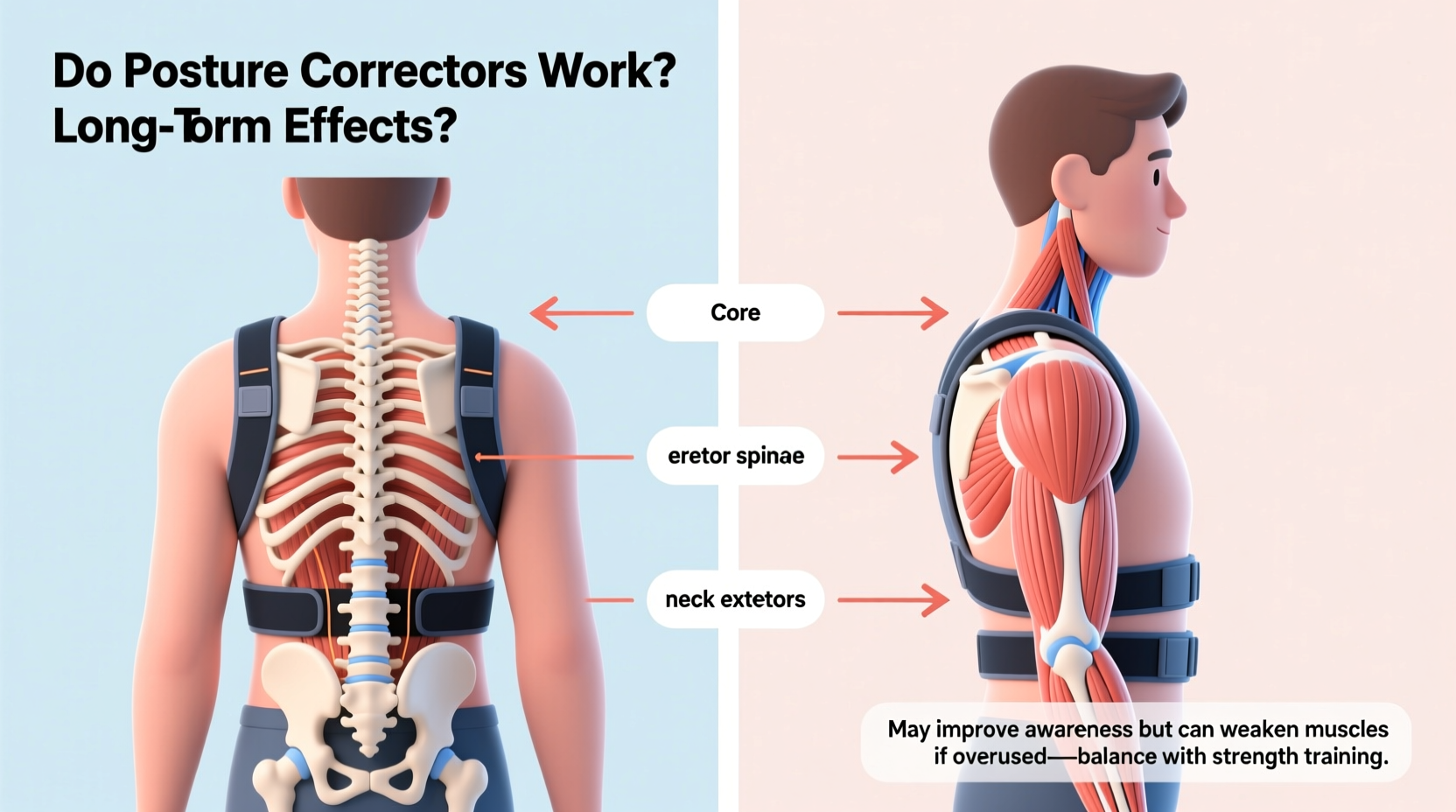

However, this correction is passive. The brace does the work, not the muscles. Over time, if the wearer becomes dependent on the device, the postural muscles—particularly the rhomboids, lower trapezius, and deep cervical flexors—may become less active. This raises a critical concern: are we trading temporary comfort for long-term weakness?

The Risk of Muscle Weakening: What Science Says

Muscles adapt based on demand. When a structure like a brace consistently performs a function—such as holding the shoulders back—the neuromuscular system may downregulate activity in those stabilizing muscles. This phenomenon, known as \"muscle inhibition,\" is well-documented in rehabilitation literature.

A 2020 study published in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies examined electromyographic (EMG) activity in participants wearing posture braces over a four-week period. Researchers found a significant decrease in activation of the middle and lower trapezius muscles during daily tasks, suggesting that reliance on external support led to reduced muscular recruitment—even when the brace was removed.

“External bracing can create a false sense of correction,” says Dr. Lena Patel, a physical therapist specializing in ergonomic rehabilitation.

“The body learns to offload effort to the device instead of engaging intrinsic stabilizers. Without concurrent strengthening, this can accelerate postural decline once the brace is discontinued.”

In essence, posture correctors may act like crutches: useful temporarily after an injury, but detrimental if used indefinitely without rehabilitating the underlying weakness.

When Posture Correctors Help—and When They Don’t

Not all use of posture correctors is harmful. Like any tool, effectiveness depends on context, duration, and integration with other strategies. Below is a breakdown of scenarios where they can be beneficial versus situations where they may do more harm than good.

| Scenario | Beneficial? | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term use during desk work | Yes | Serves as a biofeedback tool to interrupt habitual slouching |

| Rehabilitation after shoulder surgery | Yes | Provides stability during early recovery under medical supervision |

| Daily wear for 6+ hours | No | Increases risk of muscle inhibition and joint stiffness |

| Used without exercises or awareness | No | Fails to address root cause; promotes dependency |

| As part of a corrective exercise program | Yes | Can reinforce proper alignment while building motor control |

The key distinction lies in intent. If the goal is to *retrain* posture through awareness and strength, a corrector can be a transitional aid. If the goal is to *mask* poor posture indefinitely, it becomes counterproductive.

Building Sustainable Posture: A Step-by-Step Guide

Lasting postural improvement doesn’t come from strapping yourself into a brace—it comes from re-educating your nervous system and strengthening underused muscles. Here’s a practical, evidence-based approach to correcting slouching without risking muscle atrophy.

- Assess Your Baseline: Stand sideways in front of a mirror. Ideally, your ear should align over your shoulder, hip, knee, and ankle. Note any forward head position or rounded shoulders.

- Improve Thoracic Mobility: Spend 5 minutes daily on foam rolling or using a lacrosse ball against tight upper back muscles. Follow with cat-cow stretches and thoracic rotations to restore spinal movement.

- Strengthen Key Muscles: Focus on low-weight, high-repetition exercises:

- Rows with resistance bands (3 sets of 12)

- Prone Y-T-W raises (3 sets of 10 each)

- Chin tucks (to engage deep neck flexors)

- Practice Postural Awareness: Set hourly reminders to check your alignment. Sit on a firm chair, feet flat, pelvis slightly tilted forward. Imagine a string pulling the crown of your head toward the ceiling.

- Integrate Movement Breaks: Every 30 minutes, stand up and perform wall angels (back against wall, arms sliding up and down) to reinforce proper shoulder mechanics.

- Use a Corrector Strategically: Wear it for 15–20 minutes during focused work sessions, but only after activating your postural muscles. Remove it and reassess whether you can maintain the position independently.

This timeline builds neuromuscular control gradually:

- Weeks 1–2: Focus on awareness and mobility

- Weeks 3–4: Begin strengthening with light resistance

- Weeks 5–6: Reduce reliance on the brace; test unassisted posture endurance

- Week 7+: Maintain with regular movement and periodic self-assessment

Real Example: Office Worker Transforms Posture Without Long-Term Bracing

Mark, a 38-year-old software developer, had been using a posture brace daily for three months. Initially, he felt relief from neck pain and believed his posture was improving. But over time, he noticed increased fatigue in his upper back when not wearing the brace. His shoulders would slump within minutes of removing it.

After consulting a physical therapist, Mark learned he had developed significant weakness in his scapular stabilizers. He stopped wearing the brace full-time and began a targeted exercise program including band pull-aparts, dead bugs, and seated pelvic tilts. He also adjusted his workstation: raising his monitor to eye level and using a footrest to maintain a neutral spine.

Within eight weeks, Mark could sit upright for hours without support. His neck pain decreased by 80%, and EMG testing showed improved muscle activation patterns. The brace hadn’t fixed his posture—it had masked a deeper issue until it became harder to correct.

Better Alternatives to Braces

Instead of relying on passive devices, consider these proactive solutions:

- Ergonomic Workspace Design: Position monitors at eye level, use an adjustable chair with lumbar support, and keep elbows at 90 degrees.

- Dynamic Sitting: Use a balance ball or wobble cushion to encourage micro-movements that activate core and postural muscles.

- Yoga and Pilates: These disciplines emphasize spinal alignment, core stability, and body awareness—key components of healthy posture.

- Postural Taping: Kinesiology tape applied by a trained professional can provide sensory feedback without restricting movement or causing muscle inhibition.

- Professional Assessment: A physical therapist can identify specific imbalances and prescribe individualized corrective exercises.

Unlike braces, these methods promote active participation in posture correction, fostering resilience rather than dependency.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can posture correctors permanently fix slouching?

No. Posture correctors cannot permanently fix slouching on their own. Lasting change requires strengthening weak muscles, improving mobility, and developing postural awareness. Braces may assist temporarily but do not address the underlying biomechanical issues.

Are posture correctors safe for long-term use?

Long-term, continuous use is not recommended. Prolonged wear can lead to muscle deactivation, joint stiffness, and skin irritation. If used, limit sessions to 15–30 minutes and combine with active exercises to prevent dependency.

At what age should someone start using a posture corrector?

Children and adolescents should avoid posture braces unless prescribed by a healthcare provider. During growth, musculoskeletal development is highly adaptable. Focus should be on ergonomics, physical activity, and education—not external support. Adults may use them cautiously as part of a broader strategy.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Role of Posture Correctors

Posture correctors are not inherently good or bad—they are tools, and their value depends on how they're used. Worn occasionally to heighten awareness or support recovery, they can play a helpful role. But marketed as a standalone solution, they mislead users into believing that structural change comes from external force rather than internal strength.

The real fix for slouching isn’t a strap or a vest. It’s consistent movement, intelligent exercise, and mindful alignment throughout the day. Muscles respond to challenge, not constraint. To build lasting posture, you must engage the systems designed to support it—not bypass them.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?