In an age where desk jobs dominate and screen time is at an all-time high, poor posture has become a widespread concern. Slouching over laptops, craning necks toward phones, and sitting for hours without movement have led to a surge in back, neck, and shoulder pain. In response, posture correctors—brace-like garments designed to pull shoulders back and align the spine—have flooded the market. Sold with promises of instant improvement and lasting results, they’ve become a go-to solution for many. But do they truly fix posture, or do they simply mask the problem while creating new ones?

The truth lies somewhere between promise and peril. While some users report short-term relief and improved awareness, others find themselves increasingly reliant on these devices, unable to maintain proper alignment once the brace comes off. Understanding whether posture correctors are a helpful tool or a crutch requires examining how they work, what the research says, and what long-term strategies offer more sustainable solutions.

How Posture Correctors Work: The Mechanics Behind the Design

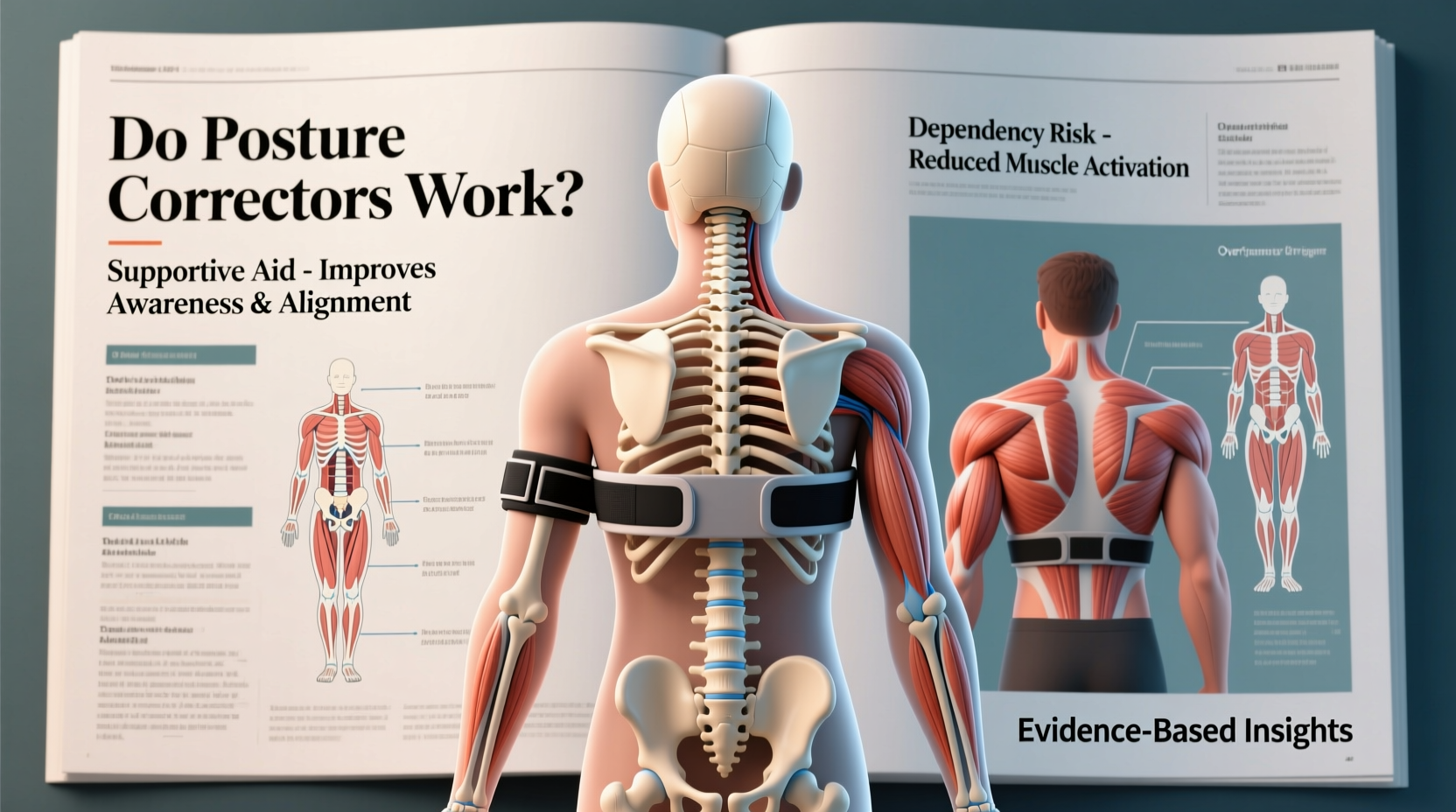

Posture correctors typically consist of straps that wrap around the shoulders and upper back, pulling them into a retracted position. Some models include additional support along the spine or chest closure systems. Their primary function is mechanical: to physically prevent slouching by limiting forward shoulder roll and rounding of the upper back (kyphosis).

When worn, these devices force the body into what appears to be ideal posture—shoulders back, chest open, head aligned over the spine. For someone who spends most of the day hunched, this can feel corrective, even enlightening. Many users describe an immediate sense of standing taller and breathing more deeply.

However, this correction is external. It does not involve active engagement from the muscles responsible for maintaining posture—the rhomboids, lower trapezius, deep cervical flexors, and core stabilizers. Instead, it outsources postural control to fabric and tension.

The Science: What Research Says About Efficacy and Muscle Impact

Scientific evidence on posture correctors remains limited but revealing. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Physical Therapy Science examined the effects of wearing a posture brace during computer work. Participants showed improved thoracic curvature while wearing the device, but no significant change in muscle activation patterns. Once the brace was removed, posture reverted within minutes.

Another concern raised by physiotherapists is muscle atrophy through prolonged use. When a device consistently holds the shoulders back, the postural muscles receive fewer neural signals to activate. Over time, this can lead to weakening—a phenomenon known as “muscle inhibition.”

“Bracing can be useful in acute rehabilitation settings, but chronic reliance disrupts neuromuscular feedback loops essential for natural posture.” — Dr. Lena Torres, DPT, Spine Rehabilitation Specialist

This mirrors findings in other areas of orthopedics. Just as prolonged use of knee braces can weaken quadriceps, constant reliance on a posture corrector may compromise the very muscles needed for upright alignment. The body adapts to its environment; if it doesn’t need to stabilize itself, it stops trying.

Risks of Dependency: When Help Becomes Harm

Dependency isn’t just theoretical—it’s frequently reported among regular users. Consider the case of Daniel, a 34-year-old software developer who began wearing a posture corrector after developing chronic neck pain. Initially, he felt relief. After four weeks, however, he noticed discomfort whenever he wasn’t wearing the brace. His shoulders felt like they were “collapsing forward” on their own.

Daniel’s experience reflects a common pattern: short-term sensory feedback replaced long-term strength development. Without concurrent exercises to build postural endurance, his muscles became less capable of functioning independently.

Other potential risks include:

- Skin irritation from friction or pressure points

- Overcorrection, leading to unnatural spinal positioning

- Reduced respiratory efficiency due to restricted ribcage movement

- Psychological dependence, where users feel incapable of good posture without assistance

These issues underscore a critical point: posture is not a static position but a dynamic skill—one that must be trained, not enforced.

Better Alternatives: Building Real Postural Strength

If posture correctors provide only temporary fixes and risk long-term setbacks, what actually works? The answer lies in neuromuscular re-education: training the brain and body to maintain alignment through awareness, movement, and strengthening.

Unlike passive bracing, active interventions promote lasting change. These include targeted exercises, ergonomic adjustments, and mindful habits integrated into daily life.

Step-by-Step Guide to Developing Sustainable Posture

- Assess Your Baseline: Stand sideways in front of a mirror. Check if your ear lines up with your shoulder, hip, and ankle. Note any forward head posture or rounded shoulders.

- Optimize Your Workspace: Adjust chair height so feet are flat, knees at 90 degrees, and monitor at eye level. Use a lumbar roll if needed.

- Practice Neutral Spine Awareness: Lie on your back with knees bent. Gently press your lower back into the floor, then release. Repeat 10 times to learn pelvic tilt control.

- Strengthen Key Muscles: Focus on rows, scapular retractions, chin tucks, and planks three times per week.

- Take Movement Breaks: Every 30–45 minutes, stand, stretch, and walk for 2–3 minutes to reset muscle tone.

Effective Exercises for Postural Support

| Exercise | Muscles Targeted | Frequency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall Angels | Rhomboids, Lower Trap, Shoulder Stabilizers | 3 sets of 10, daily | Perform slowly; keep contact with wall throughout |

| Banded Rows | Middle Back, Rear Delts | 3 sets of 12, 3x/week | Use light resistance; focus on squeeze between shoulder blades |

| Chin Tucks | Deep Neck Flexors | 2 sets of 15, daily | Prevents “text neck”; do seated or lying down |

| Plank Holds | Core, Glutes, Spinal Stabilizers | 3 x 30 seconds, every other day | Maintain straight line from head to heels |

When (and How) a Posture Corrector Might Be Useful

Despite their limitations, posture correctors aren't inherently harmful—if used correctly. Like crutches after an injury, they can serve a temporary role in recovery when paired with active rehabilitation.

Physical therapists sometimes recommend short-term use for patients recovering from surgery, prolonged immobility, or severe postural dysfunction. In these cases, the brace acts as a biofeedback tool, helping individuals recognize what proper alignment feels like.

The key is integration, not substitution. A posture corrector should never replace exercise or ergonomic improvements. At best, it’s a cue—an external reminder to engage the right muscles—not the source of correction itself.

“A posture brace should be like training wheels: helpful early on, but removed as soon as balance improves.” — Dr. Marcus Lin, Orthopedic Rehabilitation Consultant

Checklist: Using a Posture Corrector Safely (If You Choose To)

- ☑ Use only for 15–30 minutes per day, maximum

- ☑ Pair with daily postural strengthening exercises

- ☑ Avoid sleeping or exercising in the device

- ☑ Stop immediately if you feel pain, numbness, or restricted breathing

- ☑ Prioritize ergonomic setup at work and home

- ☑ Reassess posture monthly to track progress without the brace

FAQ

Can posture correctors permanently fix bad posture?

No. Posture correctors cannot create lasting change because they don’t strengthen the muscles responsible for maintaining alignment. True improvement comes from consistent movement, strengthening, and habit modification—not passive support.

Are there any safe brands or types of posture correctors?

Some medical-grade braces prescribed by physical therapists are designed for short-term therapeutic use and are generally safer than consumer products. However, even these should be used under professional guidance and discontinued as strength improves.

How long does it take to improve posture naturally?

With consistent effort—including daily exercises, ergonomic adjustments, and mindfulness—most people notice improvement within 6 to 12 weeks. Lasting change typically takes 3–6 months of sustained practice.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Path to Better Posture

Posture correctors offer the allure of a quick fix, but real postural health cannot be strapped on. The human body thrives on movement, adaptation, and engagement—not immobilization. While these devices may provide momentary relief or sensory feedback, they fall short as long-term solutions and risk weakening the very systems they aim to help.

True posture improvement comes from building strength, increasing body awareness, and making sustainable lifestyle changes. It’s not about forcing the body into position—it’s about teaching it to hold itself there. This requires patience, consistency, and a shift away from quick fixes toward holistic wellness.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?