In an age where desk jobs dominate and screen time has become a daily constant, slouching has quietly evolved from occasional habit to chronic condition. Forward head posture, rounded shoulders, and a collapsed chest are now so common they’re almost normalized. Enter the posture corrector—a wearable device promising to pull your shoulders back, align your spine, and retrain your body into standing tall. But do these devices actually fix the root causes of poor posture, or are they merely offering a fleeting illusion of improvement?

The answer isn’t binary. Posture correctors can be useful tools, but their effectiveness depends entirely on how they’re used, the underlying causes of postural dysfunction, and whether they’re paired with sustainable behavioral and physical changes.

How Posture Correctors Work: The Mechanics Behind the Device

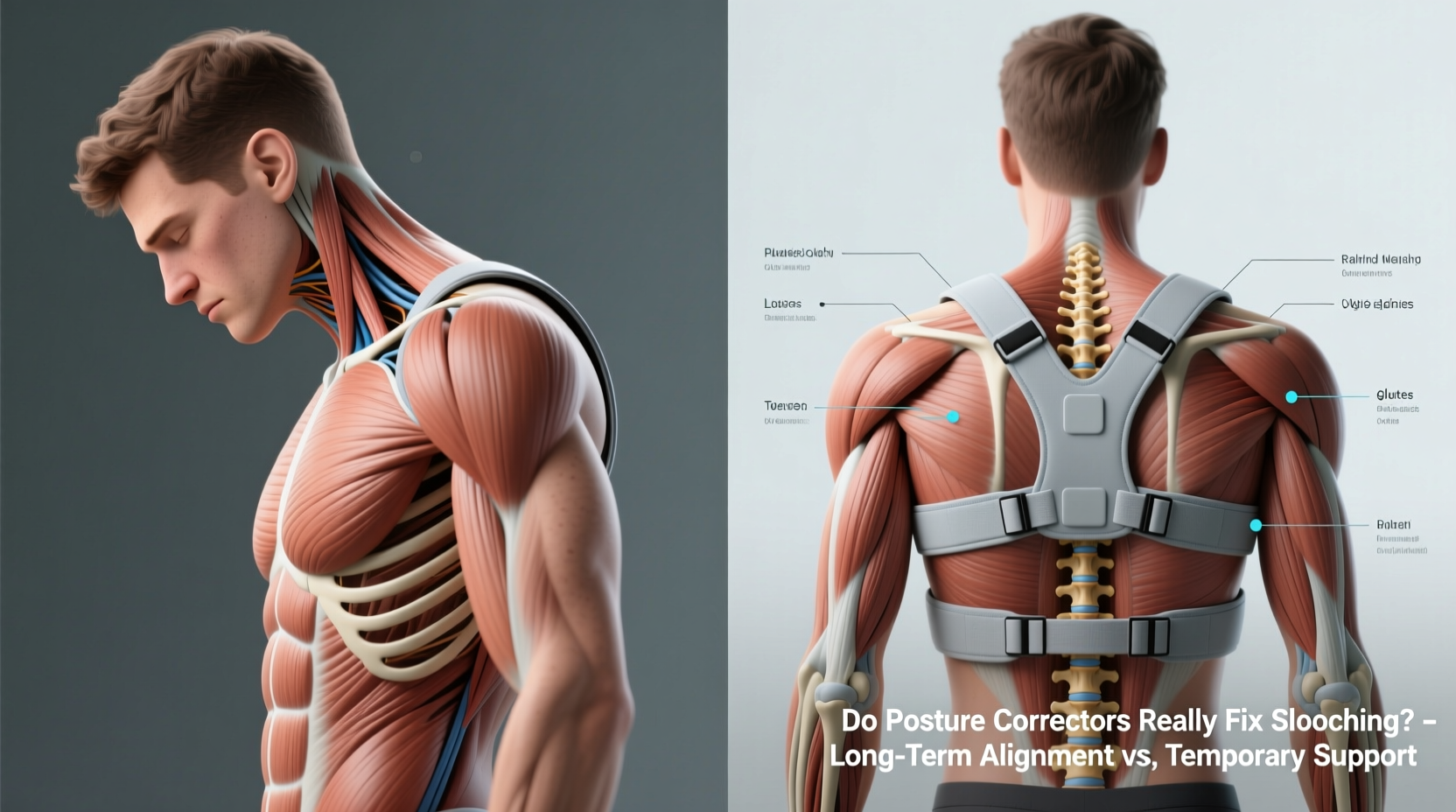

Posture correctors come in various forms—straps that wrap around the shoulders, vests, braces, and even smart wearables that vibrate when you slouch. Most function by mechanically pulling the shoulders into external rotation and retracting the scapulae (shoulder blades), which forces the upper back into extension. This realigns the spine into a more neutral position, at least temporarily.

Think of it like a cast for a broken bone: it holds the structure in place while healing occurs. In theory, consistent use “trains” the neuromuscular system to recognize proper alignment. Over time, the brain should learn to maintain this corrected posture without assistance.

However, unlike a broken bone, poor posture isn’t typically caused by acute trauma—it’s usually the result of prolonged muscle imbalances, weak postural muscles, tight chest and hip flexors, and habitual movement patterns developed over years.

The Science: What Research Says About Efficacy

Scientific evidence on posture correctors is limited but growing. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Physical Therapy Science found that participants who wore a posture brace for four weeks showed measurable improvements in shoulder angle and thoracic curvature. However, these gains were maintained only in subjects who also performed targeted strengthening exercises.

Another review in the European Spine Journal concluded that while bracing can improve spinal alignment during wear, there is insufficient evidence that it leads to long-term postural correction without concurrent exercise and education.

Neuromuscular re-education—the process of teaching your body to adopt new movement patterns—isn’t passive. It requires active engagement, repetition, and strength development. Simply strapping yourself into alignment doesn’t guarantee lasting change.

“Braces can be helpful as biofeedback tools, but they don’t replace muscle activation. Without strengthening the deep neck flexors, lower trapezius, and serratus anterior, any correction is likely to be short-lived.” — Dr. Laura Chen, DPT, Board-Certified Orthopedic Specialist

Short-Term Relief vs. Long-Term Fix: Understanding the Difference

Many users report immediate relief from neck pain, upper back tension, and headaches after using a posture corrector. This makes sense: pulling the shoulders back reduces compression on cervical nerves and decreases strain on overworked muscles like the upper trapezius and levator scapulae.

But relief is not the same as correction. Temporary symptom reduction doesn’t equate to structural or functional restoration. Consider the analogy of wearing sunglasses to reduce light sensitivity caused by staring at screens all day. The sunglasses help, but they don’t fix the root cause—excessive screen exposure.

Likewise, relying solely on a posture corrector may mask symptoms while allowing the underlying dysfunction to persist—or worsen. Overuse can lead to muscular atrophy in postural stabilizers, as the device does the work instead of your muscles.

When Posture Correctors Help—and When They Don’t

| Scenario | Benefit Level | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acute upper back pain from prolonged sitting | High (short-term) | Provides support and pain relief during recovery phase |

| Rehabilitation after injury or surgery | High | Used under professional supervision as part of a broader plan |

| Chronic forward head posture due to muscle weakness | Moderate to Low | Only effective if combined with strength training and mobility work |

| Daily wear for 6+ hours | Potentially Harmful | Risk of muscle deconditioning and joint stiffness |

| Use as a biofeedback tool | High | Worn intermittently to reinforce proper alignment awareness |

Building Sustainable Posture: A Step-by-Step Approach

If you're serious about fixing slouching—not just masking it—you need a comprehensive strategy. Here’s a proven, science-backed timeline to build lasting postural integrity.

- Week 1–2: Awareness & Assessment

Take photos of yourself from the side to assess your posture. Notice if your ear is aligned over your shoulder, your shoulder over your hip, and your hip over your ankle. Use a mirror or smartphone app to track your natural stance throughout the day. - Week 3–4: Mobility Work

Focus on releasing tight structures:- Chest (pectoralis major/minor) – use a foam roller or lacrosse ball

- Anterior neck muscles – gentle self-massage

- Hip flexors – lunging stretches

- Thoracic spine – cat-cow, foam rolling, seated twists

- Month 2: Strengthen Postural Muscles

Target often-neglected stabilizers:- Lower trapezius: Prone Y raises, wall slides

- Serratus anterior: Scapular push-ups, wall punches

- Deep neck flexors: Chin tucks, head lifts in supine position

- Core: Dead bugs, planks, bird-dogs

- Month 3+: Integrate Habits

Modify your environment and routines:- Elevate monitors to eye level

- Take standing breaks every 30 minutes

- Practice diaphragmatic breathing to engage core and stabilize spine

- Walk with arms swinging naturally to promote scapular motion

Real-World Example: Sarah’s Posture Journey

Sarah, a 34-year-old graphic designer, began experiencing sharp neck pain and frequent tension headaches after transitioning to remote work. She bought a popular posture corrector online and wore it all day for two weeks. Initially, she felt taller and less tense. But by week three, her discomfort returned—and now she felt dependent on the brace.

She consulted a physical therapist who explained that while the device provided temporary alignment, it didn’t address her weak mid-back muscles or tight pectorals. Over the next eight weeks, Sarah followed a structured program: daily mobility drills, strength exercises three times a week, ergonomic adjustments, and intermittent use of the brace only during long work sessions.

By the end of two months, Sarah no longer needed the brace. Her pain had resolved, and her posture improved significantly. More importantly, she developed body awareness—she could now feel when she was starting to slouch and correct herself instinctively.

Common Mistakes That Undermine Posture Correction

- Over-relying on the device: Treating the corrector as a permanent solution instead of a transitional aid.

- Ignoring ergonomics: Using a posture brace while still working at a poorly set up desk.

- Neglecting lower body alignment: Poor posture isn’t just upper body—tight hips and weak glutes contribute to anterior pelvic tilt, which affects spinal curves.

- Skipping consistency: Doing corrective exercises once a week won’t produce results. Daily micro-efforts compound over time.

- Using the wrong type of brace: Some correctors force extreme shoulder retraction, which can irritate the rotator cuff or cause nerve impingement.

Expert Recommendations: How to Use Posture Correctors Wisely

The consensus among physical therapists and orthopedic specialists is clear: posture correctors are most effective when used as part of a broader corrective strategy. Here’s how experts suggest integrating them:

- Limit wear time: Start with 20–30 minutes twice a day, gradually increasing to 2 hours max.

- Pair with exercise: Wear the brace before or during postural exercises to reinforce proper alignment.

- Use as a cue: Put it on during high-focus tasks (like writing or coding) to prevent drifting into slouching.

- Choose adjustable models: Avoid rigid braces; opt for ones that allow controlled movement and comfort.

- Listen to your body: If you feel pinching, numbness, or increased discomfort, stop using it immediately.

“The best posture corrector is your own nervous system trained through repetition and mindful movement. Devices can jumpstart the process, but ownership of posture comes from within.” — Dr. Rajiv Mehta, Clinical Director of Spinal Health Institute

FAQ: Your Top Questions Answered

Can posture correctors make things worse?

Yes, if used improperly. Wearing them too long or too tightly can weaken postural muscles, compress nerves, or create joint stiffness. Some designs force the shoulders into excessive retraction, leading to rotator cuff strain or thoracic outlet syndrome.

How long does it take to fix slouching?

Noticeable improvements can occur in 4–6 weeks with consistent effort. However, fully ingrained postural habits developed over years may take 6–12 months of dedicated work to retrain. The key is consistency, not speed.

Are there alternatives to posture correctors?

Absolutely. Yoga, Pilates, resistance training focusing on scapular stability, and ergonomic workspace redesign are all effective non-device approaches. Additionally, apps with posture reminders or wearable sensors (like Lumo Lift) offer feedback without restrictive straps.

Conclusion: Toward Lasting Postural Health

Posture correctors are neither miracle cures nor useless gadgets. They occupy a middle ground—they can be valuable tools when used correctly, but they cannot replace the hard work of building strength, mobility, and body awareness. Slouching is a symptom of deeper biomechanical and behavioral patterns. Addressing it requires more than a strap; it demands a lifestyle shift.

If you choose to use a posture corrector, do so intentionally. Wear it briefly to reinforce proper alignment, then remove it and test your ability to maintain that position on your own. Combine it with targeted exercises, ergonomic adjustments, and mindfulness. Over time, the goal isn’t to depend on the device—but to outgrow the need for it.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?