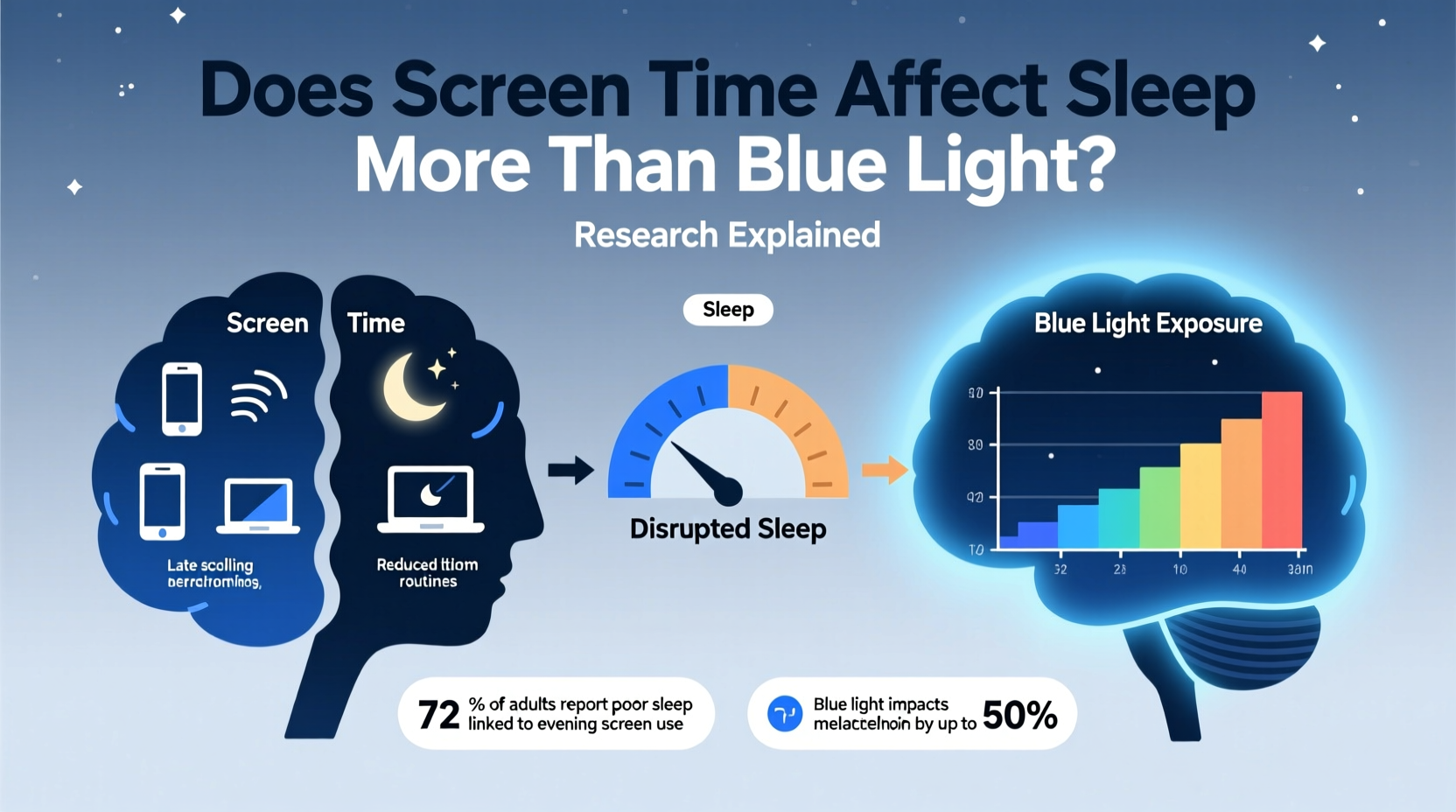

In an age where digital devices are woven into nearly every part of daily life, concerns about their impact on sleep have grown substantially. For years, the conversation has centered on blue light—its ability to suppress melatonin and disrupt circadian rhythms. But recent research suggests that focusing solely on blue light may be missing a larger picture. What if it’s not just the color of the light, but the nature and timing of our screen use that’s truly undermining sleep quality? This article examines the latest scientific findings to clarify whether overall screen time or blue light exposure plays a more significant role in disrupting sleep—and what you can do about it.

The Blue Light Hypothesis: What We Thought We Knew

Blue light, which is emitted in high amounts by LED screens (phones, tablets, computers, TVs), has long been considered the primary culprit behind poor sleep. The logic is biologically sound: short-wavelength blue light is particularly effective at suppressing melatonin, the hormone responsible for signaling sleep onset. Exposure to blue light in the evening delays this signal, tricking the brain into thinking it’s still daytime.

Studies from Harvard Medical School and others have demonstrated that blue light exposure in the evening can delay melatonin production by up to three hours, shift circadian rhythms later, and reduce rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. These findings led to the widespread adoption of “night mode” settings, blue light-blocking glasses, and apps designed to filter out blue wavelengths after sunset.

“Blue light is a potent circadian disruptor, especially when encountered during the biological night.” — Dr. Steven Lockley, Neuroscientist, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

However, while the biological mechanism is clear, real-world outcomes tell a more complex story. A 2020 meta-analysis published in JAMA Ophthalmology reviewed over 30 studies on blue light filters and found only minimal improvements in sleep quality. This raised a critical question: Is blue light really the main issue—or are we overlooking something more fundamental?

Screen Time vs. Blue Light: Untangling the Variables

Newer research indicates that total screen time—regardless of blue light filtering—may be a stronger predictor of poor sleep than light wavelength alone. A longitudinal study from the University of Oxford analyzed data from over 10,000 adolescents and found that those who spent more than four hours daily on screens were twice as likely to experience insomnia symptoms, even when using night mode features.

The distinction lies in the cognitive and psychological effects of screen engagement. Scrolling through social media, responding to work emails, or watching stimulating content activates the brain in ways that go beyond photoreceptor stimulation. This mental arousal increases cortisol levels, heightens alertness, and prolongs the time it takes to fall asleep—even if blue light is minimized.

Consider this: reading a thrilling novel before bed might also delay sleep, despite emitting no blue light. Similarly, a relaxing audiobook listened to on a dimmed device may have less impact than a brightly lit but emotionally neutral spreadsheet review. Context matters.

What the Research Actually Shows

A 2023 randomized controlled trial conducted at the University of Basel compared three groups of participants in the hour before bedtime:

| Group | Evening Activity | Melatonin Onset Delay | Sleep Latency (Time to Fall Asleep) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reading on tablet with blue light filter | 22 minutes | 18 minutes |

| 2 | Reading on tablet without filter | 35 minutes | 25 minutes |

| 3 | Interactive gaming on tablet (with filter) | 40 minutes | 38 minutes |

| 4 | Reading physical book (control) | 0 minutes | 10 minutes |

The results show that while blue light did delay melatonin, interactive screen use had a significantly greater impact on both hormonal timing and actual sleep onset. Even with blue light filtered, the cognitive load of gaming disrupted sleep more than passive screen use with unfiltered light.

Another study from the National Institutes of Health found that individuals who engaged in emotionally charged online interactions (e.g., heated social media debates) reported higher nighttime arousal and lower sleep efficiency, regardless of screen brightness or color temperature settings.

Behavioral Mechanisms Behind Screen-Related Sleep Disruption

Understanding why screen time affects sleep more than blue light requires examining the behavioral and neurological layers involved:

- Cognitive Stimulation: Problem-solving, decision-making, and emotional reactions during screen use activate the prefrontal cortex, making it harder to transition into restful states.

- Delayed Bedtime: The “just one more video” phenomenon leads to bedtime procrastination, reducing total sleep opportunity.

- Emotional Arousal: Stressful or exciting content increases heart rate and cortisol, counteracting relaxation.

- Habitual Use: Regular late-night screen use conditions the brain to associate the bedroom with alertness rather than sleep.

In contrast, simply filtering blue light doesn’t address these deeper behavioral patterns. It treats a symptom—light-induced melatonin suppression—without tackling the root causes of sleep disruption.

Mini Case Study: Sarah’s Sleep Transformation

Sarah, a 32-year-old marketing professional, struggled with chronic insomnia for over a year. She used her phone nightly with night mode enabled, wore blue light-blocking glasses, and kept her bedroom dark. Despite these efforts, she regularly took over an hour to fall asleep.

After consulting a sleep specialist, she was advised to replace her evening phone use with offline journaling and audiobooks. Within two weeks, her sleep latency dropped from 70 to 20 minutes. The key change wasn’t reducing blue light—it was eliminating the habit of checking work emails and scrolling through news feeds, which kept her mind in a state of hyper-vigilance.

“I thought I was doing everything right with the glasses and filters,” Sarah said. “But it wasn’t the light. It was the constant mental load.”

Practical Solutions: Beyond Blue Light Filters

While minimizing blue light remains beneficial, especially for those sensitive to circadian disruption, a broader strategy is needed for meaningful improvements in sleep quality. Here’s a step-by-step guide to rethinking your evening digital habits:

- Set a Digital Curfew: Choose a fixed time—ideally 60–90 minutes before bed—to stop using all screens. Use this time for low-stimulation activities like reading, stretching, or light conversation.

- Replace Engagement with Passive Input: If you must use a device, opt for audio-only content (podcasts, audiobooks) or static visuals (e-books with warm lighting). Avoid interactive apps.

- Use App Limits: Leverage built-in screen time tracking tools (iOS Screen Time, Android Digital Wellbeing) to set daily limits for social media and entertainment apps.

- Create a Wind-Down Ritual: Develop a consistent pre-sleep routine that signals safety and relaxation to your nervous system—such as dimming lights, sipping herbal tea, or practicing mindfulness.

- Keep Devices Out of the Bedroom: Charge phones and tablets in another room to eliminate temptation and reduce environmental cues for alertness.

Checklist: Evening Routine for Better Sleep

- ✅ Stop using screens 60–90 minutes before bed

- ✅ Dim household lights in the evening

- ✅ Avoid emotionally charged or work-related content after dinner

- ✅ Charge devices outside the bedroom

- ✅ Replace screen time with reading, journaling, or gentle music

- ✅ Maintain a consistent bedtime, even on weekends

FAQ: Common Questions About Screen Time and Sleep

Does blue light really affect sleep?

Yes, blue light can delay melatonin release and shift circadian rhythms. However, its real-world impact is often smaller than expected, especially when compared to the cognitive effects of prolonged screen engagement.

Are blue light-blocking glasses worth it?

They may help some individuals, particularly those exposed to bright screens in complete darkness. However, they are not a substitute for reducing overall screen time or avoiding stimulating content before bed.

Can I watch TV before bed if it’s not too bright?

Passive viewing of calming content on a dimmed screen may be less disruptive than interactive phone use. Still, any screen time close to bedtime can delay sleep onset. Ideally, avoid TV in the last hour before bed.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Conversation Around Screens and Sleep

The evidence is increasingly clear: while blue light plays a role in sleep disruption, it is not the dominant factor for most people. Total screen time, particularly when it involves mental engagement, emotional stimulation, or delayed bedtime, has a far greater impact on sleep quality. Focusing exclusively on blue light risks giving users a false sense of security—wearing amber glasses while scrolling through stressful content until midnight won’t lead to restful sleep.

True improvement comes from behavioral change. Reducing evening screen exposure, cultivating relaxing routines, and respecting the brain’s need for downtime are more effective than any filter or app setting. The goal isn’t to eliminate technology, but to use it intentionally—especially during the critical wind-down period before sleep.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?