Onions are a staple in kitchens around the world, prized for their ability to deepen flavor, add complexity, and transform simple ingredients into rich, aromatic dishes. Yet beyond their culinary role lies a microscopic architecture that influences everything from texture to taste. Understanding the structure of onion cells is not merely an academic exercise—it’s a window into how cooking techniques alter food at the cellular level. For chefs, educators, and home cooks alike, grasping this foundational biology leads to greater control over browning, moisture retention, and flavor development. The way an onion behaves when sliced, sautéed, or caramelized is directly tied to the integrity and composition of its individual cells. This article dissects the anatomy of onion cells with scientific clarity and practical relevance, connecting cellular biology to real-world cooking outcomes.

Definition & Overview

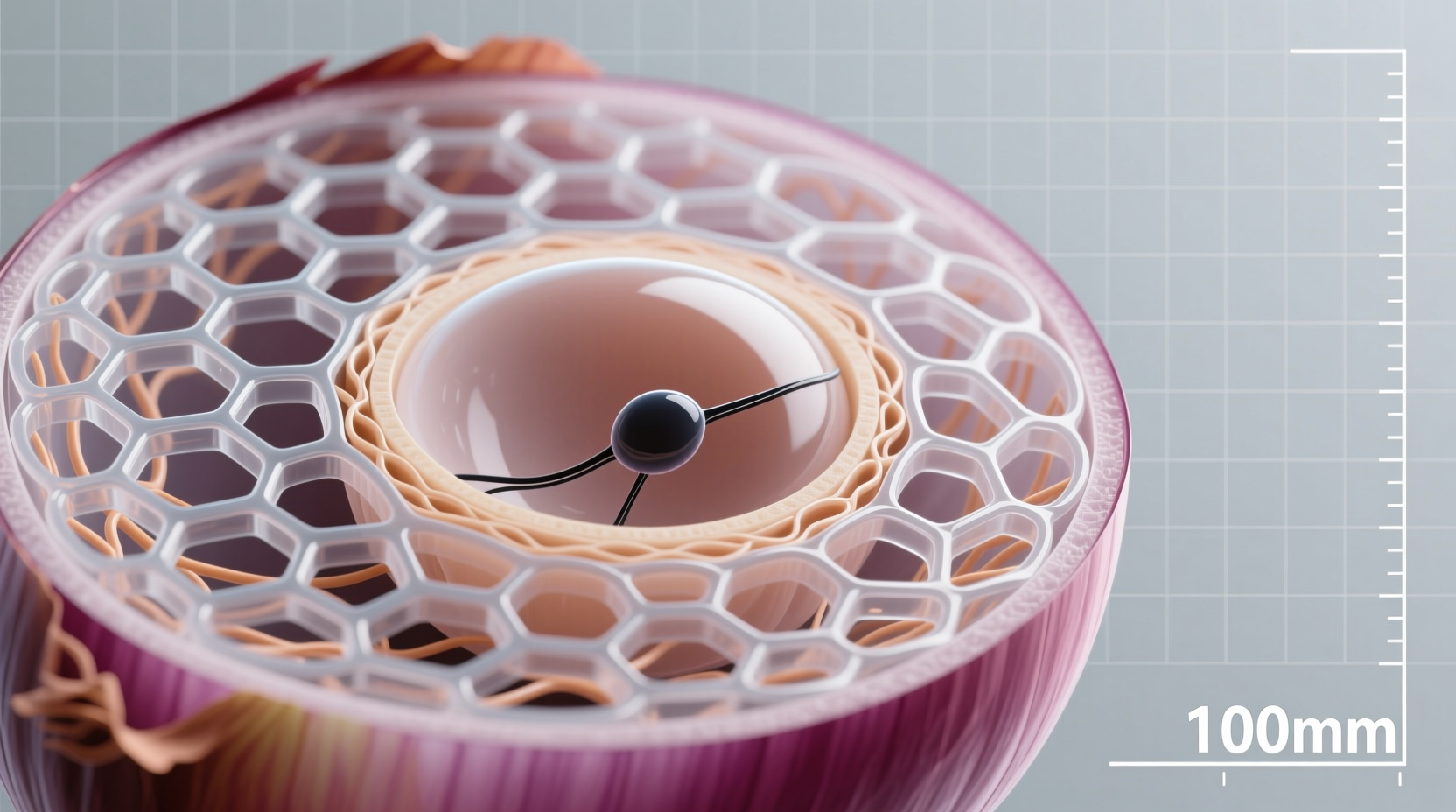

An onion (*Allium cepa*) is a bulbous vegetable belonging to the Amaryllidaceae family, closely related to garlic, leeks, and chives. Its layered structure consists of modified leaves that store nutrients, primarily carbohydrates in the form of fructans. Each layer is composed of countless plant cells arranged in tissues that provide both structural support and biochemical functionality. At the microscopic level, an onion cell exemplifies a typical plant cell but with distinct features adapted for storage and defense.

The primary function of onion cells is to store energy and water, which explains their high moisture content—approximately 89% by weight. These cells also contain sulfur-containing compounds responsible for the pungency and lachrymatory (tear-inducing) effects associated with chopping onions. When damaged, enzymes within the cells convert sulfoxides into sulfenic acids, which then rearrange into syn-propanethial-S-oxide—a volatile gas that irritates the eyes. This defense mechanism originates at the cellular level and unfolds in seconds once tissue integrity is compromised.

From a culinary science perspective, recognizing the onion’s cellular framework allows cooks to predict how heat, acid, salt, and mechanical action will affect its behavior during preparation. Whether building a mirepoix, creating a confit, or pickling slices for tacos, success hinges on manipulating these microscopic structures intentionally.

Key Characteristics of Onion Cells

The physical and chemical traits of onion cells determine their performance in recipes. Below is a breakdown of their defining attributes:

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Cell Shape & Arrangement | Polygonal or rectangular; tightly packed in epidermal and parenchyma tissues. |

| Cell Wall | Rigid, composed mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin—provides crunch and structural integrity. |

| Vacuole | Largest organelle; stores water, pigments, and secondary metabolites like flavonoids and sulfur compounds. |

| Nucleus | Contains DNA; located near the cell membrane, often visible under light microscopy. |

| Cytoplasm | Gel-like matrix housing organelles; site of enzymatic reactions such as alliinase activity. |

| Plasma Membrane | Selectively permeable barrier regulating substance flow in and out of the cell. |

| Chloroplasts | Absent in inner layers (non-photosynthetic); present in green outer shoots. |

| pH Sensitivity | Anthocyanins in red onions change color with pH—turn blue in alkaline environments, pink in acidic ones. |

| Heat Response | Cell walls break down at ~60–70°C (140–158°F), releasing water and softening texture. |

Practical Usage: How Cell Structure Influences Cooking Techniques

The way onion cells respond to various cooking methods directly impacts dish outcomes. By aligning technique with cellular behavior, cooks can achieve desired textures, flavors, and appearances.

Slicing and Cutting: Managing Enzyme Release

When a knife breaches an onion cell wall, it ruptures vacuoles containing amino acid sulfoxides and releases cytoplasmic enzymes like alliinase. Immediate mixing of these components triggers the formation of volatile sulfur compounds. To minimize tear production:

- Cut onions under cold running water or chill them before slicing—low temperatures slow enzyme kinetics.

- Use sharp knives to reduce cell crushing, limiting the number of ruptured cells.

- Work near a vent or fan to disperse the gas away from the face.

Interestingly, the same enzymatic cascade produces thiosulfinates and other organosulfur compounds that contribute to the sharp, fresh aroma of raw onions—essential in salsas, salads, and ceviches.

Sautéing and Caramelizing: Breaking Down Cell Walls

Applying heat initiates several simultaneous processes:

- Water Loss: As temperature rises, intracellular water evaporates, causing cells to shrink and collapse.

- Cell Wall Degradation: Pectin and hemicellulose in the middle lamella dissolve, weakening intercellular adhesion.

- Sugar Liberation: Fructans hydrolyze into fructose and glucose, fueling Maillard browning and caramelization.

- Flavor Transformation: Sulfur compounds volatilize or transform into more stable, savory molecules.

For true caramelization (not just softening), maintain medium-low heat for 30–45 minutes. Rapid high-heat cooking results in steaming rather than browning because released moisture prevents surface temperatures from reaching the Maillard threshold (~130°C/266°F).

Pro Tip: Add a pinch of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) during slow cooking. It raises the pH, accelerating sugar breakdown and browning—but use sparingly (⅛ tsp per large onion) to avoid mushiness or off-flavors.

Pickling: Osmosis and Turgor Pressure

Pickling relies on osmotic principles governed by cell membrane permeability. Submerging onion slices in vinegar brine (typically 5% acetic acid with salt and sugar) creates a hypertonic environment. Water flows out of the cells via osmosis, leading to partial plasmolysis—where the plasma membrane pulls away from the cell wall.

This process yields crisp-tender texture and bright acidity. Red onions undergo additional visual transformation due to anthocyanin shifts: they turn vibrant pink in acidic solutions, making them ideal garnishes for fish tacos, grain bowls, or cheese boards.

Storage and Texture Preservation

Freshness correlates with turgor pressure—the internal water pressure keeping cells rigid. Over time, respiration and transpiration deplete stored sugars and moisture, resulting in limp, less flavorful onions. Store whole onions in a cool, dry, well-ventilated space to preserve cellular integrity. Avoid refrigeration unless peeled or cut; low humidity in fridges accelerates dehydration.

Variants & Types: Cellular Differences Across Onion Varieties

While all onion cells share fundamental structures, variations in pigment, sugar content, and sulfur compound concentration lead to different culinary behaviors.

| Type | Cellular Traits | Cooking Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Yellow Onion | High sulfur, moderate sugar, thick cell walls | Ideal for long cooking; develops deep umami and golden-brown color |

| Red Onion | Rich in anthocyanins, slightly lower sulfur, thinner walls | Better raw or lightly cooked; retains crunch, adds color contrast |

| White Onion | Sharper bite, higher moisture, delicate pigmentation | Common in Mexican cuisine; preferred where clean, bright flavor is needed |

| Shallot | Smaller cells, higher fructose-to-glucose ratio, milder enzymes | Delicate sweetness; excels in reductions and vinaigrettes |

| Green Onions (Scallions) | Photosynthetically active cells (chloroplasts present), minimal storage tissue | Used raw or briefly wilted; contributes freshness and mild onion essence |

These differences stem from genetic expression and growing conditions. For instance, shallots have smaller, denser cells with tighter packing, contributing to their silkier mouthfeel when cooked slowly.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Onion cells are often compared to those of related alliums and common vegetables. Understanding distinctions helps prevent substitution errors and improves recipe fidelity.

| Ingredient | Difference from Onion Cells | Culinary Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Garlic | Cells contain allicin precursors (alliin and alliinase) in higher concentration | More intense pungency; faster enzymatic reaction upon crushing |

| Leek | Less dense cell packing, larger intercellular spaces, lower sulfur | Milder flavor; requires thorough cleaning to remove trapped soil between layers |

| Apple | Higher pectin, abundant chloroplasts even in flesh, no sulfur compounds | Crunchier raw, browns via polyphenol oxidase (different pathway), sweeter profile |

| Potato | Starch-filled amyloplasts dominate instead of vacuoles; no tear-inducing agents | Thickens sauces when broken down; gelatinizes upon heating rather than caramelizing |

One key takeaway: while apples and onions may both be used raw in salads, their cellular responses to cutting and exposure differ significantly. Apples brown quickly due to oxidation, whereas onions release gas and intensify in flavor.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Q: Why do onions make you cry, and how does cell damage cause it?

A: When cells are cut, alliinase enzymes react with sulfur-containing amino acids to produce syn-propanethial-S-oxide. This gas diffuses into the air and reacts with moisture in your eyes, forming sulfuric acid—which triggers tearing as a protective reflex.

Q: Can you prevent cellular breakdown during cooking?

A: Partially. Quick-cooking methods like stir-frying retain some cell integrity, preserving bite. Adding acid (lemon juice, vinegar) stabilizes pectin, helping maintain firmness. However, prolonged heat inevitably degrades walls through hydrolysis.

Q: Do different knife cuts affect cell rupture differently?

A: Yes. Julienne or fine dice expose more surface area, increasing enzyme access and flavor release. Thick wedges limit exposure, yielding milder results. Direction matters too: cutting across growth rings disperses more cells than slicing parallel to them.

Q: Are cooked onions less nutritious at the cellular level?

A: Some phytonutrients degrade with heat, particularly vitamin C and certain antioxidants. However, cooking increases bioavailability of others, like quercetin aglycone, which is more readily absorbed after cell wall dissolution.

Q: How long do onion cells remain viable after harvest?

A: Whole bulbs maintain cellular turgor for weeks under proper storage. Once cut, cells begin dying within hours due to oxidation and microbial invasion. Peeled onions should be refrigerated and used within 7–10 days.

Expert Insight: “The moment you slice an onion, you’re not just preparing an ingredient—you’re initiating a biochemical cascade. Mastering onion cookery means learning to guide that cascade toward your intended outcome.” — Dr. Elena Torres, Food Scientist, Culinary Institute of America

Summary & Key Takeaways

The structure of onion cells underpins their universal appeal in global cuisines. Composed of rigid, water-filled units protected by cellulose walls and governed by enzymatic systems, these cells respond predictably to mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli. Recognizing their biology empowers cooks to manipulate texture, control flavor evolution, and optimize preservation.

- Onion cells are defined by large central vacuoles, strong cell walls, and sulfur-based defense chemistry.

- Cutting damages cells, triggering enzyme-driven reactions that create aroma and tears.

- Heat breaks down pectin and cellulose, releasing sugars for browning and softening texture.

- Different onion types exhibit cellular variations affecting color, sweetness, and cooking resilience.

- Understanding osmosis, pH sensitivity, and turgor pressure improves techniques like pickling and storage.

Whether crafting a silky French onion soup or assembling a vibrant salad, awareness of cellular dynamics elevates cooking from instinct to intention. The next time you reach for an onion, remember: you're not just handling a vegetable—you're engaging with a complex biological system ripe for culinary mastery.

Apply this knowledge in your next recipe: try slow-caramelizing yellow onions with a touch of baking soda, or quick-pickle red onions using a warm vinegar solution to enhance cellular absorption. Observe the transformations—not just on the plate, but beneath the surface.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?