Bottom rot in tomatoes—commonly known as blossom end rot—is one of the most frequent disorders encountered by home gardeners and small-scale growers. Despite its alarming appearance, it is not caused by a pathogen or pest but by a physiological imbalance within the plant. Recognizing the early signs and understanding the underlying causes are essential for preserving fruit quality and yield. This condition affects the developing fruit at the blossom end—the bottom opposite the stem—and can ruin an otherwise healthy-looking tomato crop if left unaddressed. For culinary enthusiasts who grow their own produce, ensuring firm, blemish-free tomatoes is critical for salsas, sauces, salads, and roasting. Left untreated, bottom rot renders tomatoes inedible and diminishes harvest potential. The good news is that with proper cultural practices, calcium management, and watering consistency, this disorder is both preventable and manageable.

Definition & Overview

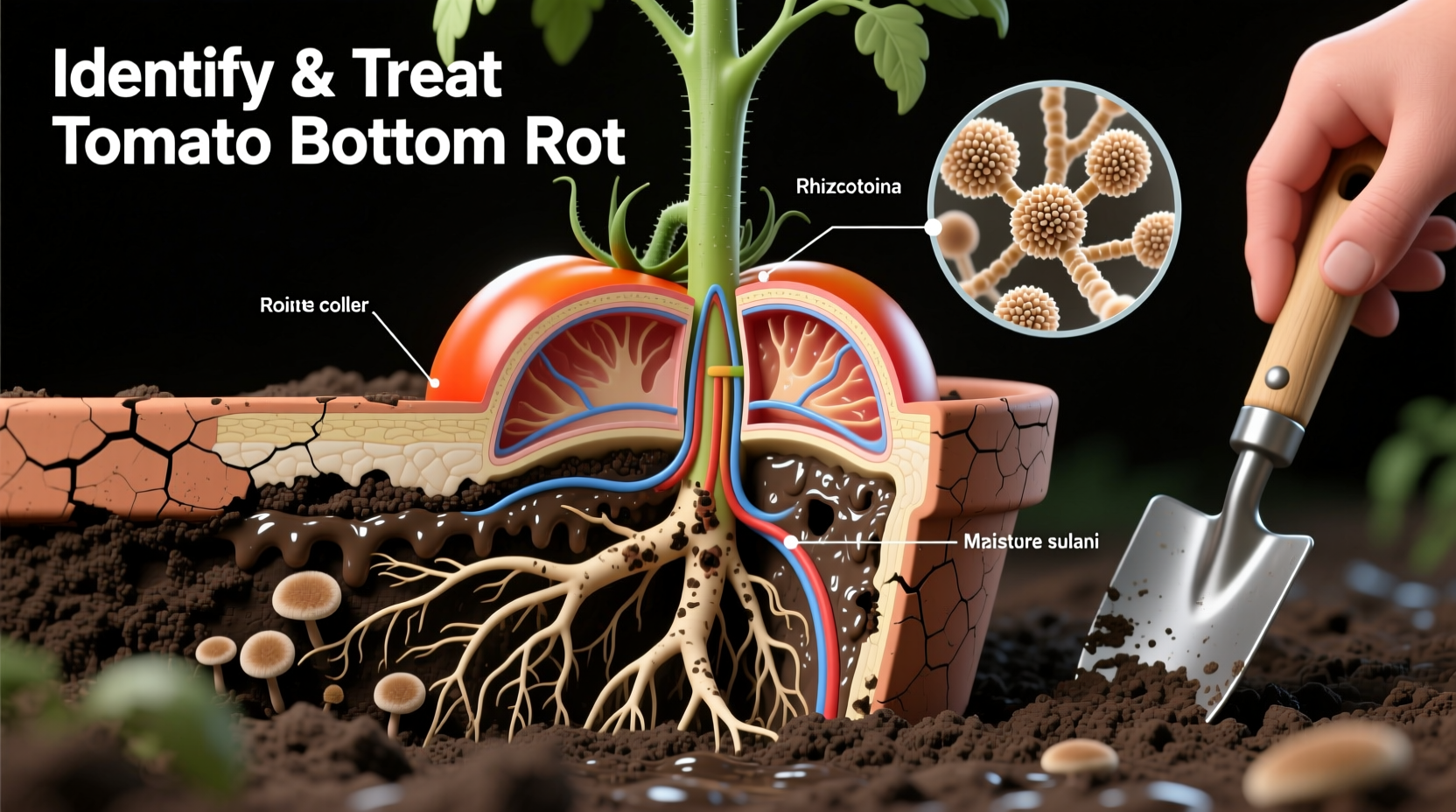

Blossom end rot (BER), often referred to as bottom rot, is a physiological disorder in tomatoes characterized by dark, sunken lesions that develop on the blossom end of the fruit. It typically appears when fruits are one-third to half their mature size. Though it resembles a fungal or bacterial infection, BER is not contagious and does not spread from plant to plant. Instead, it results from localized calcium deficiency in the fruit tissue, even when soil calcium levels are adequate. Calcium plays a crucial role in cell wall development; without sufficient delivery to developing cells, tissues break down, leading to necrotic spots. While most common in tomatoes, this condition also affects peppers, eggplants, and squash. Its occurrence is closely tied to water stress, root damage, and inconsistent nutrient uptake, making it more prevalent during periods of drought, high temperatures, or erratic irrigation.

Key Characteristics of Bottom Rot

- Visual Symptom: A small, water-soaked spot appears at the blossom end of the fruit, usually when the tomato is still green and growing.

- Progression: The spot enlarges into a leathery, sunken, dark brown or black lesion, sometimes covering up to half the fruit.

- Texture: Affected areas become dry and tough, not mushy like fungal rots.

- Internal Damage: Beneath the surface, the tissue breaks down and may appear tan or grayish.

- Timing: Symptoms first appear on the earliest maturing fruits, typically in midsummer.

- Affected Plants: Occurs primarily on otherwise healthy plants with lush foliage.

- Edibility: Severely affected fruits should be discarded; lightly affected ones can have the damaged portion cut away if no secondary rot has set in.

Tip: Do not confuse bottom rot with fungal diseases like anthracnose or fusarium rot. BER always starts at the blossom end and never spreads across the skin from the stem or sides.

Causes of Bottom Rot in Tomatoes

The primary cause of blossom end rot is insufficient calcium in the developing fruit. However, this deficiency is rarely due to a lack of calcium in the soil. More often, it stems from the plant’s inability to absorb or transport calcium effectively. Calcium moves through the plant via the transpiration stream—essentially, with water flow from roots to leaves and fruits. Any disruption in this process can lead to localized shortages in fast-growing tissues like tomato fruits.

Contributing Factors Include:

- Inconsistent Watering: Fluctuations between drought and overwatering impair calcium uptake. Dry soil limits root absorption, while saturated soil damages root function.

- Root Damage: Over-cultivation, transplant shock, or compacted soil restricts root growth and reduces nutrient uptake capacity.

- High Salinity or Excess Fertilizer: High levels of ammonium-based nitrogen fertilizers compete with calcium for uptake, exacerbating deficiency.

- Extreme pH Levels: Soil pH outside the optimal range of 6.0–6.8 reduces calcium availability, even if present in adequate amounts.

- Rapid Vegetative Growth: Heavy applications of nitrogen promote leafy growth, diverting water and nutrients away from fruits.

- High Temperatures and Low Humidity: Increase transpiration rates, causing uneven distribution of calcium within the plant.

\"Blossom end rot is less about what's missing from the soil and more about how the plant is managing what's already there.\" — Dr. Linda Chalker-Scott, Horticulturist and Extension Specialist, Washington State University

How to Identify Bottom Rot Early

Early detection is key to minimizing losses. Gardeners should inspect young fruits weekly once flowering begins. The first sign is a small, water-soaked area near the blossom scar—the dimple at the bottom of the tomato. This spot feels slightly softer than the surrounding tissue. Over 3–7 days, it expands and darkens, becoming distinctly sunken and leathery. In humid conditions, secondary molds may colonize the lesion, giving it a fuzzy appearance, but these are opportunistic, not causal.

Distinguishing BER from other issues:

| Condition | Appearance | Location on Fruit | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blossom End Rot | Dark, sunken, dry lesion | Blossom end only | Consistent moisture, balanced fertilizer |

| Anthracnose Rot | Sunken, circular spots with concentric rings | Anywhere on fruit, especially ripe ones | Fungicide, crop rotation |

| Fusarium or Southern Blight | White fungal growth with sclerotia | Stem base or ground-touching fruit | Soil solarization, sanitation |

| Cracking or Splitting | Radiating or concentric splits | Stem or shoulder area | Even watering, mulching |

Practical Treatment and Management Strategies

Once symptoms appear, immediate action can halt progression and prevent further damage. While affected fruits cannot be cured, future ones can be protected through corrective measures.

Step-by-Step Treatment Protocol:

- Remove Affected Fruit: Pick and discard all tomatoes showing signs of rot. This prevents pests and fungi from exploiting the weakened tissue and redirects plant energy to healthy fruit.

- Ensure Consistent Moisture: Provide 1–1.5 inches of water per week, adjusting for rainfall. Use drip irrigation or soaker hoses to deliver water directly to the root zone without wetting foliage.

- Apply Organic Mulch: Lay 2–3 inches of straw, shredded bark, or compost around the base of plants. Mulch conserves moisture, moderates soil temperature, and reduces evaporation.

- Test Soil pH and Nutrients: Conduct a soil test to verify calcium levels and pH. Ideal calcium concentration is 2,000–4,000 ppm; pH should be between 6.0 and 6.8.

- Add Calcium If Needed: If deficient, amend with gypsum (calcium sulfate) for neutral soils or lime (calcium carbonate) for acidic soils. Gypsum is preferred because it adds calcium without altering pH.

- Avoid High-Nitrogen Fertilizers: Switch to a balanced or low-nitrogen formula (e.g., 4-6-8 or 5-10-10). Excess nitrogen promotes leafy growth at the expense of fruit stability.

- Foliar Spray (Short-Term Aid): Apply a calcium chloride or calcium nitrate foliar spray every 7–10 days during early fruiting. Note: This is a temporary fix and does not replace root-zone calcium availability.

Pro Tip: When applying foliar sprays, do so early in the morning or late afternoon to avoid leaf burn. Ensure coverage on both upper and lower leaf surfaces for maximum absorption.

Variants and Related Conditions

While true blossom end rot affects the fruit's base due to calcium imbalance, several related disorders mimic its appearance:

- Internal Blossom End Rot: No external symptoms, but internal browning of the placental tissue. Often linked to excessive magnesium or boron deficiency.

- Tip Burn in Leafy Greens: Similar physiological response in lettuce or cabbage, caused by poor calcium transport under rapid growth.

- Pepper Blossom End Rot: Identical cause and treatment, common in bell and chili peppers.

- Brown Stain in Apples: A calcium-related storage disorder, managed similarly through pre-harvest nutrition.

Understanding these variants helps gardeners apply consistent principles across crops rather than treating each case in isolation.

Comparison with Other Tomato Disorders

It's easy to misdiagnose bottom rot as a disease. The table below clarifies distinctions:

| Disorder | Primary Cause | Treatment Approach | Organic Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blossom End Rot | Calcium imbalance / water stress | Improve watering, add calcium | Gypsum, mulch, drip irrigation |

| Early Blight | Fungal (Alternaria solani) | Fungicide, pruning, spacing | Neem oil, copper spray |

| Septoria Leaf Spot | Fungal (Septoria lycopersici) | Sanitation, fungicide | Compost tea, crop rotation |

| Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus | Viral (transmitted by thrips) | Remove infected plants | Insect control, resistant varieties |

Unlike infectious diseases, bottom rot does not require fungicides or removal of entire plants. Management focuses on environmental and nutritional correction, not eradication of pathogens.

Prevention: The Best Long-Term Strategy

Preventing bottom rot is far more effective than treating it. Proactive gardening practices reduce the likelihood of recurrence year after year.

Preventive Checklist:

- Choose resistant varieties such as ‘Mountain Pride’, ‘Celebrity’, or ‘Amelia’.

- Plant in well-drained soil rich in organic matter.

- Conduct annual soil tests before planting season.

- Amend soil with gypsum if calcium is low or pH is neutral.

- Use mulch from planting time onward.

- Irrigate consistently—avoid letting soil dry out completely.

- Space plants adequately (24–36 inches apart) for air circulation.

- Limit nitrogen-heavy fertilizers during fruit set.

- Water early in the day to allow foliage drying.

- Rotate crops every 3 years to maintain soil health.

\"The most successful tomato growers don’t react to problems—they design systems that prevent them.\" — Eliot Coleman, Organic Farming Pioneer

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I eat tomatoes with bottom rot?

If caught early and only a small portion is affected, cut away the damaged area generously and consume the rest immediately. However, once mold or soft rot develops, discard the fruit entirely. Never preserve or can tomatoes with any sign of decay.

Does milk help with blossom end rot?

Milk contains calcium and has antifungal properties, so some gardeners use diluted milk sprays (1 part milk to 2 parts water) as a supplemental treatment. While anecdotal evidence exists, scientific support is limited. It may offer mild benefit but should not replace proper irrigation and soil management.

Why do my container-grown tomatoes get bottom rot more often?

Pots dry out faster than garden beds, leading to moisture fluctuations. Use large containers (at least 5 gallons), self-watering systems, or moisture-retaining polymers. Monitor daily during hot weather and ensure drainage holes are unblocked.

Is Epsom salt good for preventing bottom rot?

No. Epsom salt (magnesium sulfate) addresses magnesium deficiency, which causes interveinal yellowing. Excess magnesium competes with calcium uptake and can worsen blossom end rot. Only apply if a soil test confirms magnesium deficiency.

How long does it take to see improvement after treatment?

New fruits should show reduced symptoms within 2–3 weeks of consistent watering and calcium application. Existing affected fruit will not recover, but new growth benefits from improved conditions.

Can over-fertilizing cause bottom rot?

Yes. High-salt fertilizers, especially those rich in ammonium nitrogen (like urea), inhibit calcium absorption. Always follow recommended rates and opt for slow-release or organic formulations like compost or fish emulsion.

Culinary Note: Healthy, firm tomatoes free of rot are essential for dishes where texture matters—think bruschetta, caprese salad, or grilled tomatoes. Preventing bottom rot ensures peak flavor and presentation.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Bottom rot in tomatoes—blossom end rot—is a non-infectious physiological disorder caused by inadequate calcium in developing fruit, usually due to inconsistent watering or root stress. It manifests as dark, sunken lesions at the blossom end and can significantly reduce yields if ignored. Though unsightly, it is preventable and manageable through sound horticultural practices.

Key points to remember:

- Blossom end rot is not a disease but a nutrient transport issue.

- Calcium deficiency in fruit often occurs despite adequate soil calcium.

- Consistent watering is the single most important preventive measure.

- Mulching, proper fertilization, and soil testing reduce risk.

- Affected fruit should be removed; new fruit can be saved with prompt action.

- Prevention through planning beats reactive treatment every time.

By understanding the physiology behind this common problem, gardeners and food lovers alike can grow stronger plants and harvest flawless tomatoes ideal for fresh eating, cooking, and preserving. With attention to water, soil, and plant balance, bottom rot becomes not a setback, but a teachable moment in sustainable gardening.

Start your next growing season with a soil test and a drip irrigation plan—two simple steps that virtually eliminate the risk of bottom rot. Share your success stories and prevention tips with fellow growers to build resilient, productive gardens.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?