Personal safety is a growing concern in many communities, prompting individuals to explore alternative protective measures. While commercial body armor undergoes rigorous testing and certification, some people consider building their own solutions at home. It's essential to understand that creating a truly bulletproof vest outside regulated manufacturing environments comes with serious limitations and risks. This guide provides a transparent, fact-based overview of what can—and cannot—be achieved through DIY methods, focusing on realistic expectations, material science, and safety awareness.

Understanding Ballistic Protection: What “Bulletproof” Really Means

The term \"bulletproof\" is often misleading. No vest is universally impervious to all threats. Instead, body armor is rated based on its ability to stop specific types of ammunition under controlled conditions. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) sets standards for ballistic resistance, classifying armor into levels such as II, IIIA, III, and IV. Each level corresponds to different rounds and velocities:

| NIJ Level | Threat Stopped | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| II | 9mm, .357 Magnum | Law enforcement concealable vests |

| IIIA | .357 SIG, .44 Magnum | Most civilian self-defense scenarios |

| III | Rifle rounds (e.g., 7.62mm FMJ) | Military or tactical gear |

| IV | Armor-piercing rifle rounds | High-threat tactical operations |

Detecting the difference between stab-resistant and ballistic protection is also crucial. Many DIY attempts result in vests that may resist sharp objects but offer little defense against high-velocity projectiles.

“Body armor performance depends on precise layering, material integrity, and certified construction. Homemade versions rarely meet even basic safety thresholds.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Materials Engineer, Ballistics Research Lab

Materials Needed for a Basic DIY Protective Panel

While a fully reliable bulletproof vest cannot be safely made at home, it is possible to assemble a rudimentary impact-resistant panel using accessible materials. This should only be viewed as an educational exercise—not a substitute for certified protection.

- Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE): Found in cut-resistant gloves or fishing line, this lightweight synthetic fiber has ballistic applications in commercial armor.

- Aramid Fabric (Kevlar® or Twaron®): Available in surplus or industrial supply stores, multiple layers are required for any meaningful resistance.

- Hard Armor Plates (optional): Ceramic or steel plates rated NIJ Level III or IV provide rifle protection but are heavy and expensive.

- Fabric Backing Material: Nylon or polyester cloth to bind layers and prevent fraying.

- Adhesive (Epoxy Resin or Spray Glue): Used to laminate sheets together and reduce delamination upon impact.

- Sewing Machine (heavy-duty): For stitching perimeter seams if not laminating entirely.

- Measuring Tape, Scissors, Gloves: Safety and precision tools.

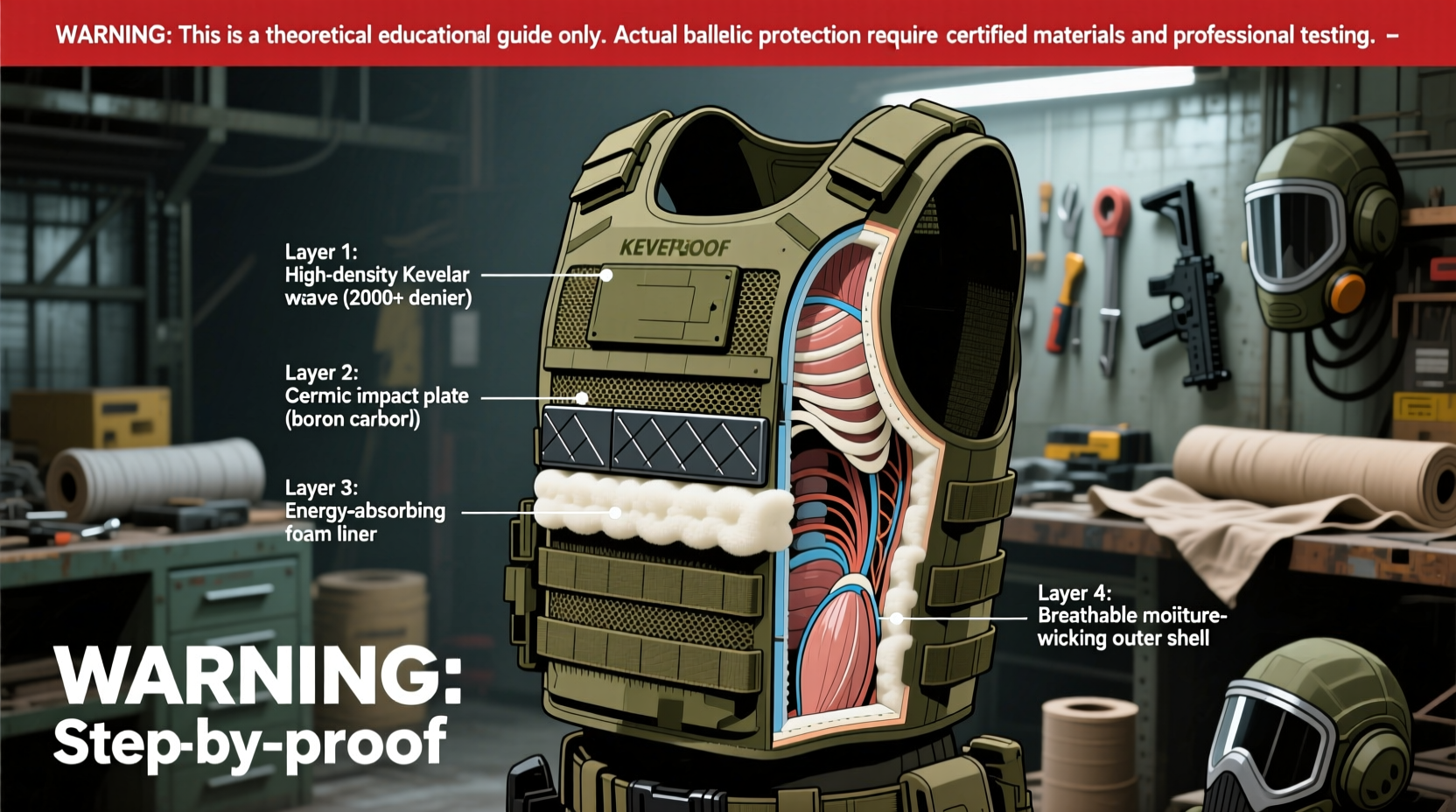

Step-by-Step Assembly Process

Below is a structured approach to assembling a layered soft armor panel. Remember: this does not guarantee protection and should never be relied upon in life-threatening situations.

- Measure and Cut Panels: Cut Kevlar or UHMWPE fabric into 12” x 12” squares (or torso-sized). Aim for at least 20–30 layers depending on thickness per sheet.

- Layer Strategically: Alternate fiber orientations (0°/90°) across layers to distribute impact energy more effectively.

- Laminate Layers: Apply thin, even coats of epoxy resin between every 5 layers. Press flat under weight for 24 hours to cure. This mimics cross-lamination techniques used in real armor.

- Add Outer Shell: Sandwich the laminated core between two pieces of durable nylon fabric. Sew around the edges with heavy thread to prevent edge unraveling.

- Test for Integrity (Non-Ballistic): Perform a puncture test using a sharpened blunt rod under pressure. If fibers tear easily, the vest lacks cohesion.

- Mount in Carrier: Insert the panel into a tactical backpack, binder, or custom carrier positioned over the chest. Ensure full front coverage without gaps.

This process may yield a barrier capable of slowing low-energy impacts, but it will not reliably stop handgun rounds like a .45 ACP or 9mm at close range unless built with industrial-grade materials and precision.

Realistic Limitations and Risks of DIY Body Armor

A mini case study illustrates the dangers of overestimating homemade protection:

In 2021, a man in Ohio constructed a vest from layered Kevlar scraps and plastic sheets after purchasing surplus fabric online. During a confrontation, he was shot once with a 9mm round. The vest absorbed partial impact but failed to stop penetration, resulting in severe internal injury. Forensic analysis revealed uneven layering, poor adhesion, and insufficient density—common flaws in DIY builds.

The takeaway: real-world performance depends on consistency, quality control, and certification testing not replicable in garages or basements.

Do’s and Don’ts of DIY Personal Protection

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Use certified armor from licensed vendors | Trust untested homemade vests in dangerous situations |

| Research NIJ standards before buying or building | Assume all Kevlar is equally effective |

| Store materials dry and away from UV light | Expose fabrics to moisture or heat long-term |

| Inspect for wear, tears, or delamination monthly | Reuse damaged or expired panels |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I legally make a bulletproof vest at home?

In the United States, yes—individuals can legally construct body armor for personal use, provided they are not felons. However, wearing body armor during a crime significantly increases penalties. Laws vary internationally; always check local regulations.

Will a stack of books or wood stop a bullet?

Possibly, but unpredictably. Some tests show phone books or plywood slowing bullets, but penetration paths are erratic and secondary fragmentation can cause injury. These materials are not viable substitutes for engineered armor.

How long does Kevlar last in a DIY setup?

Commercial Kevlar vests degrade after 5 years or exposure to water, sunlight, and folding. DIY versions degrade faster due to lack of protective coatings and environmental sealing. Inspect frequently and replace every 2–3 years if stored improperly.

Final Checklist Before Attempting Any Build

- ☐ Verify local laws regarding possession and use of body armor

- ☐ Source genuine aramid or UHMWPE fabric (not imitation)

- ☐ Confirm material specifications (gram per square meter, weave type)

- ☐ Work in a ventilated area when using resins or adhesives

- ☐ Understand that no DIY solution equals certified protection

- ☐ Prioritize avoidance, de-escalation, and legal self-defense strategies over reliance on gear

Conclusion: Knowledge Over False Security

While the idea of crafting your own bulletproof vest may seem empowering, true personal protection lies in preparation, awareness, and access to tested equipment. DIY projects can deepen understanding of material science and ballistic principles, but they should never replace professional-grade safety gear. If you're concerned about personal risk, invest in NIJ-certified armor from reputable suppliers, pair it with situational training, and consult security professionals.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?