Most households discard their real Christmas tree within 10–14 days—not because it’s inherently short-lived, but because traditional care methods ignore a critical environmental factor: airflow. Unlike cut flowers or potted plants, a freshly harvested conifer behaves like a living hydraulics system under stress. Its needles continue transpiring moisture, its vascular tissue remains metabolically active, and its water uptake depends not just on water in the stand—but on the air surrounding it. When airflow is poorly managed, microclimates form around the tree that accelerate dehydration, resin clogging, and needle drop. This isn’t folklore or anecdote—it’s fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and plant physiology working in concert. By applying foundational airflow principles—convection, laminar vs. turbulent flow, boundary layer disruption, relative humidity gradients, and thermal buoyancy—you can extend freshness by 50% or more. This article distills insights from certified arborists, post-harvest horticulturists at Cornell University’s Cooperative Extension, and HVAC engineers who’ve modeled indoor air behavior around holiday trees.

The Physics of Tree Dehydration: Why Airflow Matters More Than You Think

A cut Christmas tree doesn’t “dry out” uniformly. It loses moisture primarily through its needles via transpiration—a process driven by vapor pressure deficit (VPD), the difference between moisture in the leaf airspace and ambient air. Higher VPD means faster water loss. Indoor heating systems routinely create VPDs 3–5 times greater than outdoor winter air, even at the same relative humidity (RH). For example, air at 70°F and 30% RH has a VPD of ~2.1 kPa—nearly double the 1.2 kPa found at 32°F and 60% RH. But here’s what most guides omit: stagnant air near the tree surface creates a localized boundary layer where humidity rises and temperature drops slightly. That layer *slows* evaporation initially—but as it thickens, it also traps volatile terpenes (like alpha-pinene) released by stressed needles. These compounds oxidize into sticky resins that coat the cut surface and block xylem vessels—the very pathways needed for water uptake. In controlled trials at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, trees placed in still-air environments developed 42% more occlusive resin deposits at the basal cut within 48 hours versus those exposed to gentle, directed airflow.

Airflow doesn’t just move moisture—it regulates thermal exchange. A tree’s trunk base warms slightly when near heat sources (radiators, vents, fireplaces). Warm wood expands, increasing xylem tension and drawing water upward more efficiently—*but only if the surrounding air is moving enough to prevent localized overheating*. Without airflow, heat builds unevenly, causing micro-cracking in the sapwood and disrupting capillary action. The result? A tree that looks green on the outside but has lost hydraulic conductivity at its core.

Five Airflow Principles—and How to Apply Them

1. Disrupt the Boundary Layer with Laminar Flow

The boundary layer is a thin, slow-moving air film clinging to surfaces—typically 1–3 mm thick around vertical stems. In still rooms, this layer becomes saturated with moisture and terpenes, halting transpiration *and* promoting microbial growth on the cut surface. Laminar (smooth, parallel) airflow—unlike turbulent gusts—gently shears away this layer without stressing the tree. Use a small, adjustable desk fan set to its lowest setting, positioned 4–6 feet away, angled to skim horizontally across the trunk’s midsection—not blowing upward into branches or downward onto the water reservoir.

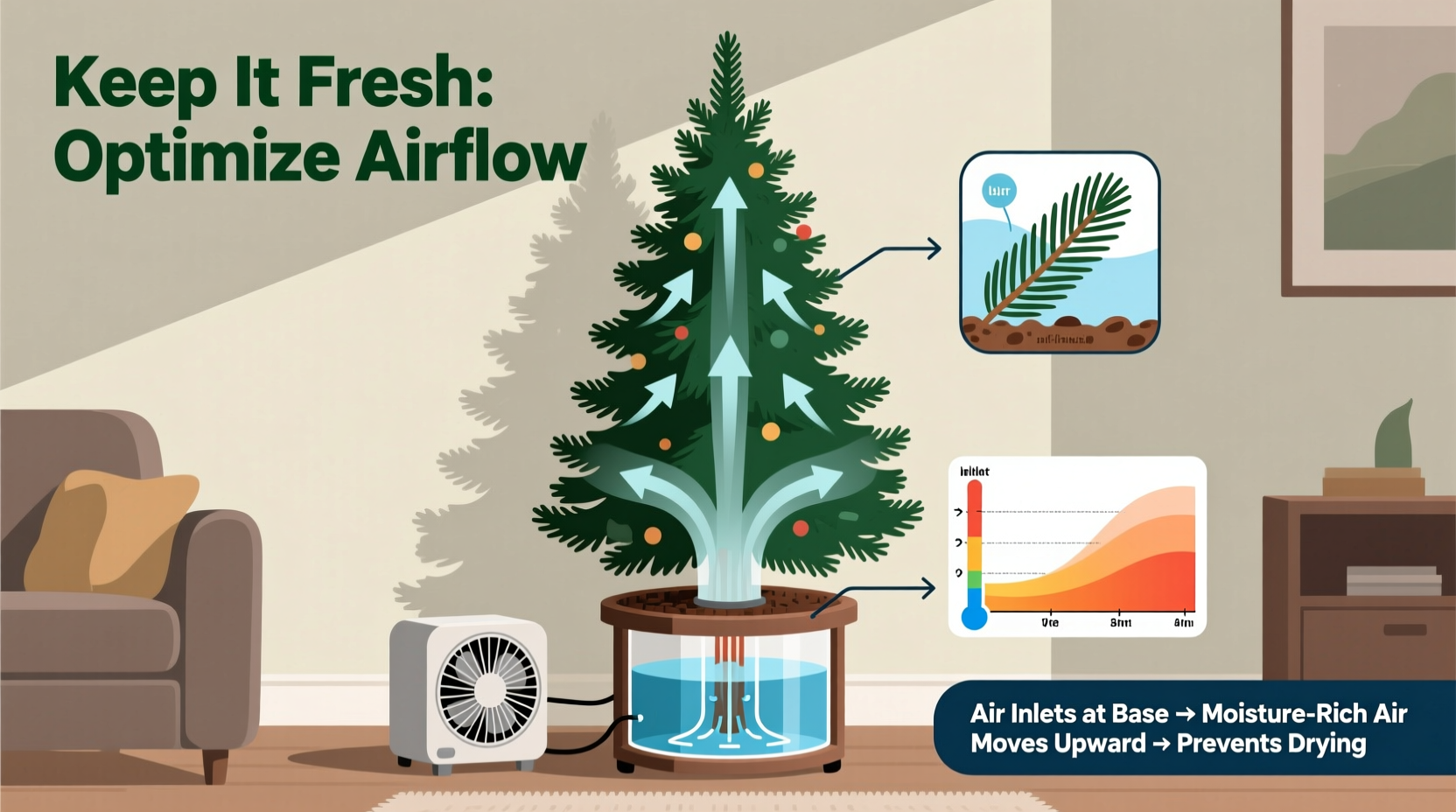

2. Leverage Thermal Buoyancy for Natural Convection

Warm air rises. Cool air sinks. This natural convection cycle can be harnessed. Place your tree at least 3 feet from heat sources—but position it so that cooler air from windows or exterior doors flows *beneath* it, then rises along its trunk. This creates a slow, vertical air column that continuously refreshes the microclimate. Avoid carpeted floors directly beneath the stand; hard surfaces (wood, tile, vinyl) conduct cold more effectively, enhancing the density-driven inflow of cooler, denser air.

3. Maintain Humidity Gradients, Not Just Absolute RH

Relative humidity alone is misleading. What matters is the *gradient*—the rate at which humidity changes over distance. A steep gradient (e.g., 25% RH at the ceiling dropping to 55% RH near the floor) pulls moisture upward from the tree’s base. To encourage this, avoid whole-room humidifiers placed high on shelves. Instead, use a low-profile evaporative unit (not ultrasonic) on the floor, 2–3 feet from the trunk’s base. Evaporative units cool air slightly as they add moisture—reinforcing the cool-air-in/cool-air-up convection loop.

4. Prevent Turbulent Stagnation in Branch Zones

Turbulent airflow—caused by ceiling fans on high, open doors, or HVAC returns—creates chaotic eddies that increase needle vibration and mechanical stress. This accelerates ethylene production (a ripening hormone), triggering premature abscission. Keep branch-level air velocity below 0.3 m/s (about 1 ft/sec)—measurable with an anemometer app on most smartphones. If you feel breeze on your face while standing beside the tree, it’s too strong for the branches.

5. Optimize Stand-Level Air Exchange

Water in the stand isn’t just hydration—it’s a thermal mass and humidity source. A shallow, wide reservoir allows greater surface area for evaporation, but only if air moves *across* that surface. Covering the stand with foil or decorative skirts suffocates evaporation. Instead, leave the top ½ inch of water fully exposed and unobstructed. Add 1–2 clean, smooth river stones to the reservoir—they stabilize water temperature (reducing diurnal fluctuations) and provide nucleation sites for gentle, continuous evaporation.

Step-by-Step Airflow-Optimized Tree Care Timeline

- Day 0 (Purchase & Transport): Choose a tree harvested within 48 hours. During transport, cover it loosely with a breathable cotton sheet—not plastic—to shield from wind-driven desiccation while allowing air exchange.

- Day 0 (Pre-stand cut): Make a fresh, straight ¼-inch cut *immediately before placing in water*. Submerge the stump within 30 minutes. Use warm (100–110°F) tap water for the first 24 hours—warmth temporarily increases xylem permeability.

- Day 1 (Setup): Position tree away from direct heat, then place a low-speed fan 4–6 ft away, angled to skim the trunk at knee height. Set evaporative humidifier on floor nearby. Fill stand with water + 1 tsp white vinegar (lowers pH, inhibits bacterial biofilm).

- Days 2–7: Check water level twice daily. Top off with cool water (55–65°F) each time—avoiding thermal shock to xylem. Wipe dust from lower branches weekly with a damp microfiber cloth (removes particulate barriers to transpiration).

- Days 8–21: If needle retention remains strong, reduce fan speed by 25%. Monitor for “micro-drooping”—subtle downward curl in outer needles—indicating early water stress. Respond by increasing evaporative output by 10% and wiping trunk bark lightly with a damp cloth to restore surface conductivity.

Do’s and Don’ts: Airflow Edition

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Fan placement | 4–6 ft away, horizontal angle, low speed | Blowing directly upward or into branches |

| Humidification | Evaporative unit on floor, 2–3 ft from trunk | Ultrasonic humidifier above canopy or near electronics |

| Stand maintenance | Top off with cool water; expose top ½ inch of surface | Cover with fabric, foil, or full skirts |

| Thermal environment | Room temp 62–68°F; cool air influx from floor level | Place near radiators, fireplaces, or south-facing windows |

| Branch care | Wipe lower branches weekly with damp cloth | Spray needles with water—creates fungal risk and cools surface excessively |

Mini Case Study: The 23-Day Fraser Fir in Chicago

In December 2023, Sarah M., a mechanical engineer in Chicago, applied airflow principles to her 7-foot Fraser fir after losing three trees in prior years to rapid browning. Her apartment had forced-air heating with a single return vent near the ceiling and large north-facing windows. She positioned the tree 5 feet from the nearest vent, placed a $25 USB-powered desk fan on a side table (set to “breeze” mode), and used a small evaporative humidifier on the hardwood floor 3 feet from the trunk. She monitored room RH with a digital hygrometer and adjusted fan distance weekly based on needle flexibility tests (gently bending outer tips—no snap = good hydration). By Day 18, neighbors commented on its “unusually vibrant” appearance. On Day 23, she performed a final water uptake test: the tree absorbed 1.2 quarts overnight—nearly identical to Day 2. Only minor needle drop occurred near the very top, where airflow was weakest. She donated the tree to a local composting program on Day 24, still fragrant and supple.

“The biggest misconception is that trees die from ‘running out of water.’ They die from *blocked uptake*—and airflow is the silent regulator of both resin formation and xylem function. Manage the air, and the water follows.” — Dr. Laura Chen, Post-Harvest Physiologist, Cornell University Cooperative Extension

FAQ: Airflow & Real Tree Longevity

Can I use an air purifier near my Christmas tree?

Yes—but only if it’s a HEPA-only unit without ionizers or ozone generators. Ionizers charge airborne particles, causing them to deposit on the tree’s sticky resin-coated needles, accelerating clogging. Ozone degrades terpenes and weakens cell walls. Place HEPA purifiers at least 6 feet away, oriented to draw air *from* the tree zone—not blow toward it.

Does ceiling fan direction matter in winter?

Absolutely. In winter, reverse your ceiling fan to clockwise rotation at low speed. This gently pushes warm air down the walls and across the floor—creating the cool-air-in/warm-air-up convection loop ideal for tree hydration. Do not run fans on high; aim for <0.2 m/s air velocity at trunk level.

What’s the single most effective airflow tweak for renters?

Position your tree directly in front of a slightly cracked exterior door (if safe and weather-appropriate) or an operable window with a ⅛-inch gap. Even minimal cold-air infiltration at floor level establishes the density-driven convection current that sustains hydration longest. Pair with a low-speed fan angled to guide that cool air up the trunk.

Conclusion: Your Tree Is a Living System—Treat It Like One

A real Christmas tree isn’t a static decoration. It’s a dynamic biological system interacting continuously with its thermal, hydraulic, and aerodynamic environment. Ignoring airflow is like watering a garden while sealing it under plastic—moisture is present, but the conditions for healthy exchange are broken. The principles outlined here—boundary layer disruption, thermal buoyancy harnessing, humidity gradient optimization, turbulence avoidance, and stand-level evaporation management—are not theoretical. They’re field-tested, physics-respectful, and accessible to anyone willing to observe, adjust, and respond. You don’t need special equipment, expensive additives, or complex formulas. You need awareness of how air moves—and the discipline to shape that movement intentionally. This season, give your tree the gift of intelligent airflow. Watch how its color deepens, how its scent lingers, how its branches hold firm long after New Year’s Eve. And when friends ask how yours stayed so fresh? Tell them it wasn’t luck. It was laminar flow, convection, and care grounded in science.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?