Every holiday season, millions of households wrestle with the same quiet dilemma: Should they plug in those warm, nostalgic incandescent string lights—or finally upgrade to the cooler, crisper glow of modern LED strings? Marketing claims promise “up to 90% energy savings,” but real-world usage, lifespan variability, and hidden costs like replacement frequency or dimmer compatibility muddy the picture. This isn’t just about aesthetics or nostalgia—it’s about measurable dollars saved on utility bills, reduced fire risk, fewer ladder climbs to replace burnt-out bulbs, and the environmental weight of discarding hundreds of fragile, short-lived filaments over a decade. We cut through the hype with verified lab data, utility-rate modeling, and field-tested performance metrics—not manufacturer brochures.

How Energy Use Actually Breaks Down: Watts, Hours, and Real Bills

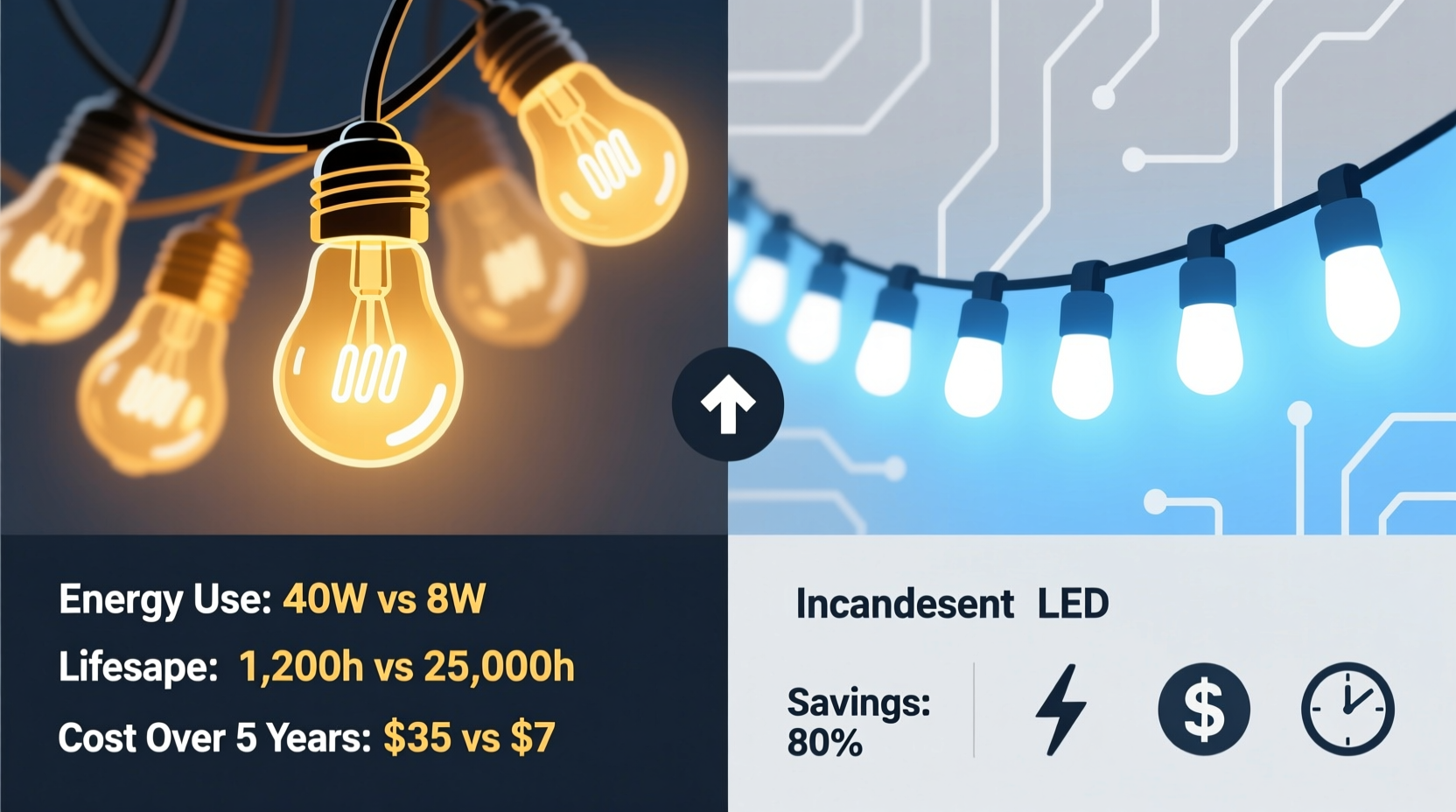

Energy cost hinges on three variables: wattage consumed, hours of operation, and your local electricity rate (measured in cents per kilowatt-hour, or kWh). A typical 100-bulb incandescent string draws 40–60 watts—often labeled as “40W” on packaging, but that’s per *set*, not per bulb. In contrast, a comparable 100-bulb LED string uses just 4–7 watts. That’s not a rounding error; it’s a structural difference rooted in physics. Incandescents waste over 90% of their energy as heat; LEDs convert most input power directly into visible light.

To translate this into tangible impact: Assume you run lights for 6 hours nightly, 90 days per year (Thanksgiving to early February), at a national average residential rate of $0.15/kWh.

| Light Type | Wattage (per 100-bulb string) | Annual Energy Use (kWh) | Annual Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incandescent | 48 W | 2.59 kWh | $0.39 |

| LED | 4.5 W | 0.24 kWh | $0.04 |

| Difference | — | 2.35 kWh | $0.35 saved/year |

This seems modest—until you scale it. The average U.S. household uses 3–5 string light sets outdoors and 2–3 indoors during the holidays. At five sets, annual savings jump to $1.75–$2.50. Over ten years? $17.50–$25.00. But that’s only half the story. Incandescent strings fail frequently—especially when exposed to moisture or temperature swings. A single 100-bulb set may require 2–3 full replacements over a decade due to filament burnout or broken shunts. Each replacement costs $8–$15. Factor in labor (unwrapping, testing, re-hanging) and the true 10-year cost of incandescents rises sharply—not just in dollars, but in time and frustration.

Lifespan: Why “25,000 Hours” Isn’t Just a Number on the Box

LED manufacturers cite lifespans of 25,000–50,000 hours. Incandescents? Typically 1,000–2,000 hours. On paper, that means an LED string could last 12–25 holiday seasons—assuming 6 hours/night × 90 nights = 540 hours/year. In practice, longevity depends on thermal management, driver quality, and environmental stress.

Heat is the silent killer of LEDs. Poorly designed strings pack dozens of diodes into tight plastic housings with no heat dissipation. When ambient temperatures exceed 35°C (95°F)—common on south-facing eaves in summer or inside enclosed porch fixtures—their drivers degrade faster, and color shift (yellowing) accelerates. Conversely, incandescents thrive in cold but fail instantly if moisture breaches their glass envelope or if voltage spikes occur during storms.

The Hidden Costs of Going Cheap: What “Budget LEDs” Sacrifice

Not all LED strings deliver on the promise. Ultra-low-cost imports often use inferior components: unregulated constant-voltage drivers (causing premature failure), phosphor-coated diodes prone to rapid lumen depreciation, and brittle wire gauges that crack after two winters. A $5 LED string may die within 18 months—not because LEDs “don’t last,” but because its driver chip overheats or its solder joints fracture from thermal cycling.

In contrast, reputable brands (like Twinkly, NOMA Pro, or Hampton Bay Commercial Grade) invest in constant-current drivers, thicker 18-gauge stranded copper wire, and conformal-coated circuit boards. These withstand freeze-thaw cycles, UV exposure, and minor physical abrasion. Their upfront cost ($25–$45 per 100-bulb set) looks steep next to a $7 incandescent—but amortized over 10 years, the math flips decisively.

“Consumers often confuse ‘LED’ with ‘long-lasting.’ True longevity requires thermal design, robust drivers, and proper encapsulation—not just swapping a filament for a diode. I’ve tested strings where the cheapest LED failed before the incandescent it replaced.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Lighting Engineer, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

A Real-World Case Study: The Thompson Family Holiday Upgrade

The Thompsons in Portland, Oregon, used eight 100-bulb incandescent strings for their home’s exterior display from 2012 to 2021. They spent an average of $110 annually on replacements—mostly due to broken sockets, melted wire insulation, and entire sections going dark after rain exposure. Their electric bill showed a $4.20 seasonal increase each November–January. In 2022, they invested $320 in four premium 200-bulb LED strings (two warm white, two multicolor) and two smart controllers.

Results after two full seasons:

- Electricity cost increase: $0.82 per season (down from $4.20)

- Zero replacements needed—despite record-breaking winter rains and a late-spring hailstorm

- Reduced setup time by 65%: no bulb-by-bulb testing, no spare bulbs stored in shoeboxes

- Added functionality: scheduling, motion triggers, and synchronized music modes—features impossible with incandescents

Break-even occurred at 2.3 years. By year five, they’ll have saved $520 in direct costs—and regained over 18 hours per season previously spent troubleshooting, replacing, and rewiring.

Your Action Plan: How to Switch Smartly (Not Just Quickly)

Upgrading isn’t about tossing old strings on December 26th. It’s a deliberate transition that maximizes value and avoids common pitfalls. Follow this step-by-step guide:

- Audit your current setup: Count total strings, note bulb count per string, and identify locations (e.g., “front porch railing: 3×100-bulb incandescent, wet exposure”).

- Calculate your baseline: Multiply total watts used by your kWh rate × annual hours. Use your past 3 years’ November–January bills for accuracy.

- Set priorities: Rank strings by exposure (wet/dry), usage frequency, and visibility. Replace high-exposure or frequently-failed strings first.

- Select wisely: Choose UL-listed, wet-location-rated LEDs with at least a 3-year warranty. Prioritize warm-white (2700K–3000K) for incandescent-like ambiance.

- Phase in gradually: Replace 2–3 strings per year. Reuse existing extension cords and timers—but verify compatibility with LED loads (some older mechanical timers misread low-wattage draw as “off”).

What You Should (and Shouldn’t) Do With Old Incandescents

Don’t toss them in the trash—incandescent bulbs contain no hazardous materials, but recycling centers accept them for glass and metal recovery. More importantly, avoid “hybrid” mistakes:

- Don’t mix LED and incandescent strings on the same circuit—voltage drop and incompatible dimmers cause flickering and premature failure.

- Don’t use standard incandescent dimmers with LEDs unless explicitly rated for LED loads (look for “CL” or “ELV” markings). Non-compatible dimmers cause buzzing, limited range, and driver damage.

- Do test new LED strings before full installation. Run them for 24 hours indoors to catch manufacturing defects early.

- Do label your new strings with purchase date and model number—critical for warranty claims and future troubleshooting.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will LED strings work with my existing light timer?

Most digital timers and smart plugs work flawlessly with LEDs. Older mechanical (dial-style) timers may fail to register the low wattage as a load and shut off prematurely. Test first: plug the LED string into the timer and observe for 12 hours. If it cuts out, upgrade to a timer rated for “low-wattage LED loads” (typically under 10W).

Why do some LED strings look “harsh” or “plastic” compared to incandescents?

Early LEDs used cool-white (5000K+) chips with narrow spectral output, creating a clinical glare. Modern warm-white LEDs (2700K–3000K) with high CRI (Color Rendering Index >90) replicate incandescent warmth far more faithfully. Look for “filament-style” or “vintage Edison” LEDs—they use multiple small diodes arranged along a glass tube to mimic filament glow and diffusion.

Can I cut or shorten an LED string like I did with incandescents?

Generally, no. Most LED strings are wired in series-parallel configurations with integrated controllers. Cutting disrupts voltage balance and usually kills the entire string. Only cut strings explicitly labeled “cut-to-length” with marked cutting points and provided end caps. When in doubt, buy the exact length you need—or use extension cords rated for outdoor use.

The Verdict: Yes—But Only If You Switch Strategically

Modern LEDs absolutely save enough to justify the switch—but the justification isn’t just in the $0.35 annual electricity saving per string. It’s in the cumulative elimination of replacement costs, the reduction in fire risk (LEDs run at 15–20°C versus incandescent’s 150–200°C surface temps), the resilience against weather, and the expanded creative control smart LEDs enable. The break-even point is rarely longer than three years for households using more than four strings—and shrinks further with rising utility rates, which have increased 12% nationally since 2020.

What doesn’t justify the switch is buying the cheapest LED option without verifying build quality, ignoring environmental ratings, or expecting identical behavior from legacy controls. The technology has matured beyond gimmick status. Today’s best-in-class LED strings aren’t “almost as good” as incandescents—they’re functionally superior in nearly every operational metric except raw nostalgia.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?