When reviewing a complete blood count (CBC) report, one value that often raises concern is MCH — Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin. If your lab results show low MCH levels, it’s natural to wonder what this means for your health. MCH measures the average amount of hemoglobin inside your red blood cells. Hemoglobin is essential for carrying oxygen from your lungs to tissues throughout the body. When MCH falls below the normal range — typically less than 27 picograms (pg) per cell — it can signal an underlying condition, most commonly a form of anemia.

Understanding low MCH isn’t just about recognizing a number on a chart; it’s about identifying potential root causes, addressing nutritional gaps, and preventing long-term complications such as fatigue, weakness, and impaired cognitive function. This article breaks down what low MCH truly indicates, explores its most frequent causes, and provides practical steps for diagnosis and correction.

What Is MCH and Why Does It Matter?

MCH stands for Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin. It reflects the average mass of hemoglobin in a single red blood cell. The calculation is derived by dividing the total hemoglobin by the red blood cell count:

MCH (pg) = Hemoglobin (g/dL) × 10 / Red Blood Cell Count (millions/µL)

The normal reference range for MCH is generally between 27 and 33 picograms per cell. Values below 27 pg are classified as low. While MCH alone doesn't diagnose a condition, it serves as a critical clue when interpreted alongside other CBC parameters like MCV (Mean Corpuscular Volume), MCHC (Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration), and RDW (Red Cell Distribution Width).

Low MCH often correlates with microcytic anemia — a condition where red blood cells are smaller than normal and contain less hemoglobin. This reduces the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity, leading to systemic symptoms.

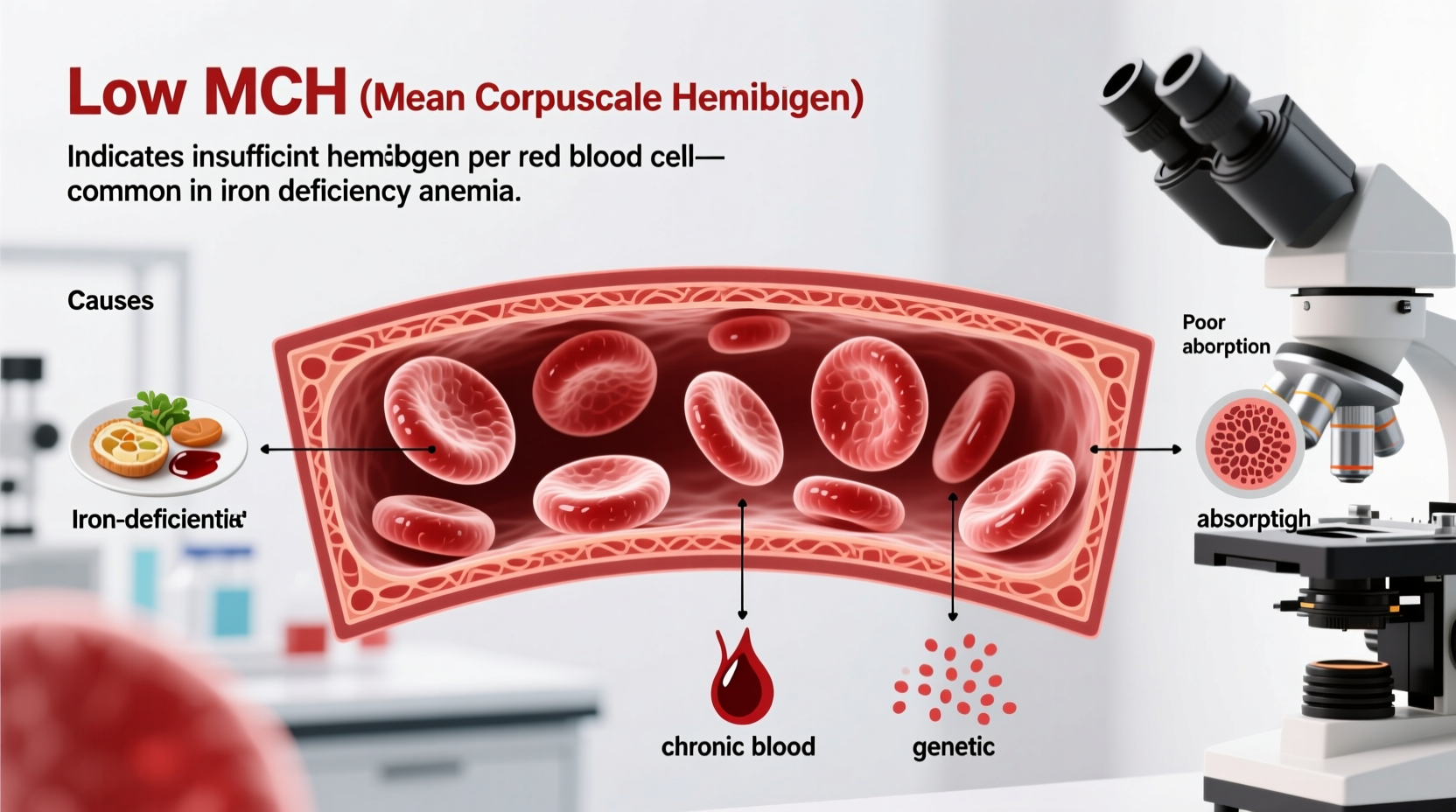

Common Causes of Low MCH Levels

Low MCH is not a diagnosis in itself but a sign pointing toward specific health issues. The most prevalent causes include:

Iron Deficiency Anemia

This is the leading cause of low MCH worldwide. Iron is essential for hemoglobin production. When iron stores are depleted — due to poor dietary intake, chronic blood loss (such as heavy menstrual periods or gastrointestinal bleeding), or malabsorption — the body cannot produce sufficient hemoglobin. As a result, red blood cells become small and pale, reflected in low MCH and MCV values.

Thalassemia

A genetic blood disorder, thalassemia affects hemoglobin synthesis. Unlike iron deficiency, thalassemia often presents with disproportionately low MCV relative to MCH. It's more common in people of Mediterranean, African, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian descent. In mild cases, individuals may be asymptomatic, but severe forms require medical management.

Chronic Disease Anemia

Long-term inflammatory conditions — such as rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, or cancer — can disrupt iron metabolism and red blood cell production. This type of anemia usually shows normocytic or mildly microcytic cells, but MCH may still fall below normal.

Poor Nutrition

Diet lacking in iron, vitamin B6, copper, or protein can impair hemoglobin synthesis. Vegetarians and vegans, especially those not supplementing or consuming fortified foods, are at higher risk if plant-based iron (non-heme) isn’t paired with vitamin C to enhance absorption.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Conditions like celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or gastric bypass surgery can interfere with nutrient absorption, particularly iron and B vitamins, leading to chronically low MCH over time.

“Low MCH is a red flag that should prompt further investigation into iron status and possible hidden blood loss, especially in adults.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Hematology Specialist

Recognizing Symptoms of Low MCH

Many people with mildly low MCH may not experience immediate symptoms. However, as hemoglobin levels continue to drop, signs of tissue hypoxia emerge. Common symptoms include:

- Fatigue and weakness

- Pale skin (especially in lips, gums, and inner eyelids)

- Shortness of breath during mild exertion

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Cold hands and feet

- Difficulty concentrating

- Irritability

- Frequent headaches

In children, prolonged low MCH can affect growth and cognitive development. In older adults, it may exacerbate cardiovascular strain and increase fall risk due to reduced stamina.

Diagnostic Process: What Happens Next?

If your CBC reveals low MCH, your healthcare provider will likely order follow-up tests to determine the cause. These may include:

- Serum Ferritin – Measures iron stores; low levels confirm iron deficiency.

- Iron and TIBC (Total Iron-Binding Capacity) – Evaluates circulating iron and transport capacity.

- Transferrin Saturation – Calculates how much iron is bound to transferrin.

- Hemoglobin Electrophoresis – Used to detect thalassemia traits.

- Reticulocyte Count – Assesses bone marrow response to anemia.

- Fecal Occult Blood Test or Endoscopy – To rule out gastrointestinal bleeding in adults.

A thorough patient history — including diet, menstrual patterns, medication use, and family history — is equally important in narrowing down the cause.

Treatment and Management Strategies

Correcting low MCH depends entirely on the underlying cause. General approaches include:

Dietary Improvements

Incorporate iron-rich foods such as lean red meat, poultry, fish, lentils, spinach, tofu, and fortified cereals. Pair plant-based iron sources with vitamin C-rich foods (like oranges, bell peppers, or strawberries) to boost absorption.

Iron Supplementation

Oral iron supplements (ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate) are commonly prescribed for iron deficiency. They work best on an empty stomach but may cause constipation or nausea. Taking them with a small amount of food or splitting the dose can improve tolerance.

Treating Underlying Conditions

If thalassemia is diagnosed, regular monitoring and sometimes blood transfusions or chelation therapy are needed. For chronic disease-related anemia, managing the primary illness is key. In cases of GI blood loss, treating ulcers, polyps, or inflammatory bowel disease is essential.

Lifestyle Adjustments

Avoid excessive tea, coffee, or calcium supplements around meals, as they inhibit iron absorption. Space these items at least one hour before or after iron-rich meals.

Do’s and Don’ts When Addressing Low MCH

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Eat iron-rich foods daily | Ignore persistent fatigue or paleness |

| Take iron supplements as directed | Self-diagnose and over-supplement without testing |

| Pair iron with vitamin C for better absorption | Drink coffee or tea with iron-containing meals |

| Follow up with your doctor after treatment starts | Assume symptoms will resolve immediately — recovery takes weeks |

| Investigate causes of blood loss (e.g., heavy periods) | Disregard family history of blood disorders |

Real-Life Example: Identifying the Root Cause

Sarah, a 32-year-old teacher, visited her doctor complaining of constant tiredness and difficulty focusing at work. Her CBC showed low MCH (24 pg) and low MCV. At first, she assumed it was stress. But further testing revealed very low serum ferritin (8 ng/mL), confirming iron deficiency anemia. Upon discussion, Sarah admitted having heavy menstrual periods for years and following a mostly plant-based diet without iron supplementation. She began taking ferrous sulfate and increased her intake of lentils, pumpkin seeds, and broccoli with lemon dressing. Within three months, her MCH normalized, and her energy returned. Her case highlights how combining clinical data with lifestyle insight leads to effective treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can low MCH occur without anemia?

Yes. Early iron deficiency may show low MCH before hemoglobin drops below normal, known as \"latent iron deficiency.\" This stage is crucial for early intervention before full-blown anemia develops.

Is low MCH dangerous?

Chronically low MCH can lead to significant health issues, including weakened immunity, heart strain from compensating for low oxygen, and developmental delays in children. However, when identified and treated early, outcomes are excellent.

How long does it take to correct low MCH?

With proper treatment, MCH levels typically begin improving within 2–4 weeks. Full correction of iron stores may take 3–6 months, even after symptoms resolve. Continuous supplementation is often needed to replenish reserves.

Conclusion: Take Action Before Symptoms Worsen

Low MCH is more than a lab anomaly — it’s a window into your body’s oxygen delivery system. Whether caused by diet, blood loss, or genetics, identifying the reason behind low MCH empowers you to make informed health decisions. Don’t dismiss fatigue or paleness as “just part of life.” Request a CBC if you're at risk, especially if you have heavy periods, follow restrictive diets, or have digestive conditions. With timely testing, targeted treatment, and consistent follow-up, most causes of low MCH are fully manageable.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?