Factoring is a foundational skill in algebra that unlocks the ability to simplify expressions, solve equations, and understand polynomial behavior. Among the most useful factoring patterns is the difference of squares. Recognizing and applying this pattern efficiently can save time and reduce errors in both academic and real-world problem-solving scenarios. This guide breaks down the concept into manageable steps, illustrates it with practical examples, and equips you with strategies to master it confidently.

Understanding the Difference of Squares Pattern

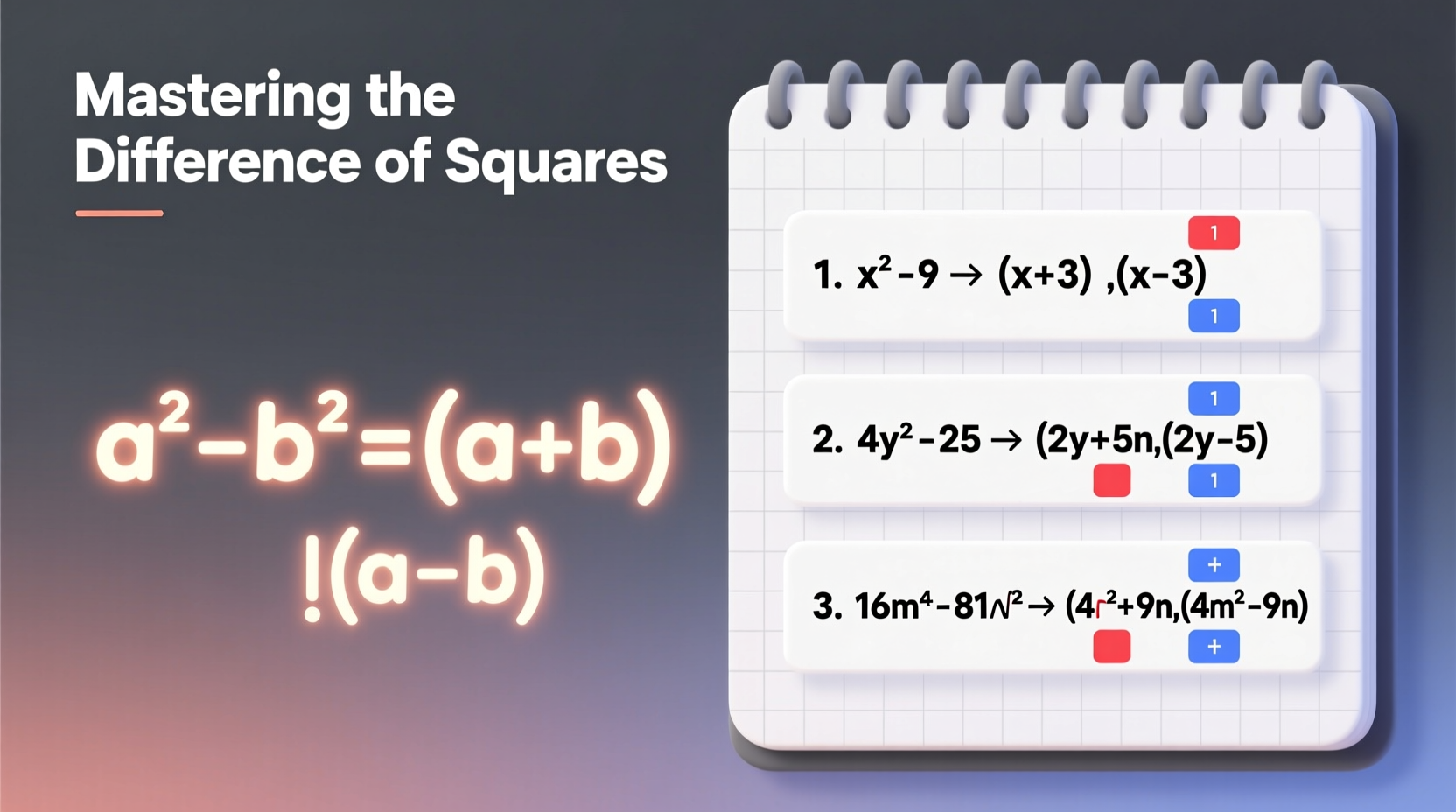

The difference of squares refers to a binomial expression in the form \\( a^2 - b^2 \\). What makes this special is that it can always be factored into the product of two binomials: \\( (a + b)(a - b) \\). This identity holds true for any real numbers, variables, or algebraic expressions substituted for \\( a \\) and \\( b \\), as long as both terms are perfect squares and separated by subtraction.

For example:

- \\( x^2 - 9 = (x + 3)(x - 3) \\)

- \\( 4y^2 - 25 = (2y + 5)(2y - 5) \\)

- \\( 16a^4 - b^6 = (4a^2 + b^3)(4a^2 - b^3) \\)

The key lies in identifying whether each term is a perfect square and whether the operation between them is subtraction. Addition, such as \\( x^2 + 4 \\), does not fit this pattern and cannot be factored using the difference of squares over the real numbers.

Step-by-Step Guide to Factoring the Difference of Squares

Follow this systematic process to factor any expression that fits the difference of squares pattern.

- Check the structure: Confirm the expression has exactly two terms and is in the form \\( \\text{Term}_1 - \\text{Term}_2 \\).

- Verify both terms are perfect squares: Each term must be the square of some number, variable, or expression. For instance, \\( 9x^2 \\) is \\( (3x)^2 \\), and \\( 16y^4 \\) is \\( (4y^2)^2 \\).

- Take the square root of each term: Identify \\( a \\) and \\( b \\) such that \\( a^2 = \\text{first term} \\) and \\( b^2 = \\text{second term} \\).

- Apply the formula: Write the factored form as \\( (a + b)(a - b) \\).

- Simplify if necessary: Distribute coefficients or further factor nested differences if applicable.

Example 1: Basic Case

Factor \\( x^2 - 64 \\).

- Structure: Two terms, subtracted — good.

- Perfect squares: \\( x^2 = (x)^2 \\), \\( 64 = (8)^2 \\).

- Square roots: \\( a = x \\), \\( b = 8 \\).

- Apply: \\( (x + 8)(x - 8) \\).

Answer: \\( x^2 - 64 = (x + 8)(x - 8) \\).

Example 2: With Coefficients

Factor \\( 25y^2 - 49 \\).

- Structure: Subtraction of two terms — valid.

- Perfect squares: \\( 25y^2 = (5y)^2 \\), \\( 49 = (7)^2 \\).

- Square roots: \\( a = 5y \\), \\( b = 7 \\).

- Apply: \\( (5y + 7)(5y - 7) \\).

Answer: \\( 25y^2 - 49 = (5y + 7)(5y - 7) \\).

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced students make mistakes when rushing through factoring. The following table outlines frequent errors and corrections.

| Mistake | Why It's Wrong | Correct Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Trying to factor \\( x^2 + 16 \\) as difference of squares | Addition is not subtraction; no real factors exist via this method | Recognize that sum of squares doesn’t factor over reals |

| Writing \\( 9x^2 - 4 \\) as \\( (9x + 4)(9x - 4) \\) | Incorrectly took square roots; should be \\( (3x)^2 \\) and \\( (2)^2 \\) | Use \\( (3x + 2)(3x - 2) \\) |

| Forgetting to factor out a GCF first | Expression like \\( 4x^2 - 36 \\) needs GCF 4 factored first | Write as \\( 4(x^2 - 9) = 4(x + 3)(x - 3) \\) |

Advanced Applications and Nested Differences

Some expressions involve multiple layers of differences of squares. These require recursive factoring.

Example 3: Factoring a Fourth-Degree Polynomial

Factor \\( x^4 - 81 \\).

- Recognize \\( x^4 = (x^2)^2 \\), \\( 81 = (9)^2 \\).

- First factor: \\( (x^2 + 9)(x^2 - 9) \\).

- Notice \\( x^2 - 9 \\) is also a difference of squares: \\( (x + 3)(x - 3) \\).

- \\( x^2 + 9 \\) cannot be factored further over the reals.

Final answer: \\( x^4 - 81 = (x^2 + 9)(x + 3)(x - 3) \\).

Mini Case Study: Solving a Real Equation

A student is asked to solve \\( 4x^2 = 100 \\). Instead of dividing both sides immediately, they rewrite it as:

\\( 4x^2 - 100 = 0 \\)

They factor out the GCF: \\( 4(x^2 - 25) = 0 \\)

Then apply difference of squares: \\( 4(x + 5)(x - 5) = 0 \\)

Using the zero-product property: \\( x = -5 \\) or \\( x = 5 \\)

This method reinforces conceptual understanding over rote memorization and reduces calculation errors.

“Students who master factoring patterns like the difference of squares develop stronger algebraic intuition, which pays off in calculus and beyond.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Mathematics Education Researcher

Checklist: Mastering the Difference of Squares

Use this checklist whenever you encounter a binomial to determine if it’s a difference of squares and how to proceed:

- ☐ Is the expression a binomial (exactly two terms)?

- ☐ Is there a minus sign between the terms?

- ☐ Are both terms perfect squares? (Think: Can I take the square root evenly?)

- ☐ Have I factored out the GCF already, if one exists?

- ☐ Did I apply \\( a^2 - b^2 = (a + b)(a - b) \\) correctly?

- ☐ Can either factor be broken down further (e.g., another difference of squares)?

- ☐ Does multiplying the factors return the original expression? (Always verify!)

Frequently Asked Questions

Can the difference of squares be used with fractions or decimals?

Yes. As long as both terms are perfect squares, the pattern applies. For example, \\( \\frac{1}{4}x^2 - \\frac{9}{16} = \\left(\\frac{1}{2}x + \\frac{3}{4}\\right)\\left(\\frac{1}{2}x - \\frac{3}{4}\\right) \\). Just ensure you’re taking the square root of both the numerator and denominator correctly.

What if the variables have even exponents but aren't squared directly?

As long as the exponent is divisible by 2, the term is a perfect square. For instance, \\( x^6 = (x^3)^2 \\), so \\( x^6 - y^8 = (x^3 + y^4)(x^3 - y^4) \\). Focus on whether the entire term can be expressed as something squared.

Is there a sum of squares formula?

Over the real numbers, no. Expressions like \\( a^2 + b^2 \\) do not factor using real binomials. However, in complex numbers, \\( a^2 + b^2 = (a + bi)(a - bi) \\), where \\( i = \\sqrt{-1} \\). But for standard algebra, treat sum of squares as non-factorable via this method.

Conclusion: Build Confidence Through Practice

Factoring the difference of squares is more than a mechanical trick—it's a gateway to deeper algebraic fluency. Once you internalize the pattern, you’ll begin spotting it instinctively in quadratic equations, rational expressions, and even geometry problems involving area. The key is consistent practice with varied examples, from simple binomials to multi-layered polynomials.

Start with basic problems, use the checklist to build discipline, and gradually tackle more complex cases. Over time, this skill will become second nature, freeing mental space for higher-level thinking in advanced math courses.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?