Water rockets are more than just backyard fun—they’re a dynamic fusion of physics, engineering, and experimentation. While launching a soda bottle skyward is simple, achieving peak performance requires understanding one crucial variable: the air-to-water ratio. Getting this balance right can mean the difference between a 30-foot launch and a 200-foot flight. This article breaks down the science behind optimizing that ratio using fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and practical testing.

The Physics Behind Water Rocket Propulsion

Water rockets operate on Newton’s Third Law: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. When pressurized air forces water out through a nozzle, the expelled mass generates thrust, propelling the rocket upward. Unlike solid-fuel rockets, water rockets rely on stored potential energy in compressed air, which converts to kinetic energy as water is ejected.

The efficiency of this conversion depends heavily on two factors: the mass of the propellant (water) and the pressure of the gas (air). Too much water means excessive mass without enough pressurized gas to expel it rapidly. Too little water reduces thrust duration. The sweet spot lies in balancing these elements to maximize impulse—the product of thrust and time.

“Optimal performance isn’t about max pressure or max water—it’s about synergy between mass ejection and gas expansion.” — Dr. Alan Hirsch, Aerospace Education Specialist, National Rocketry Association

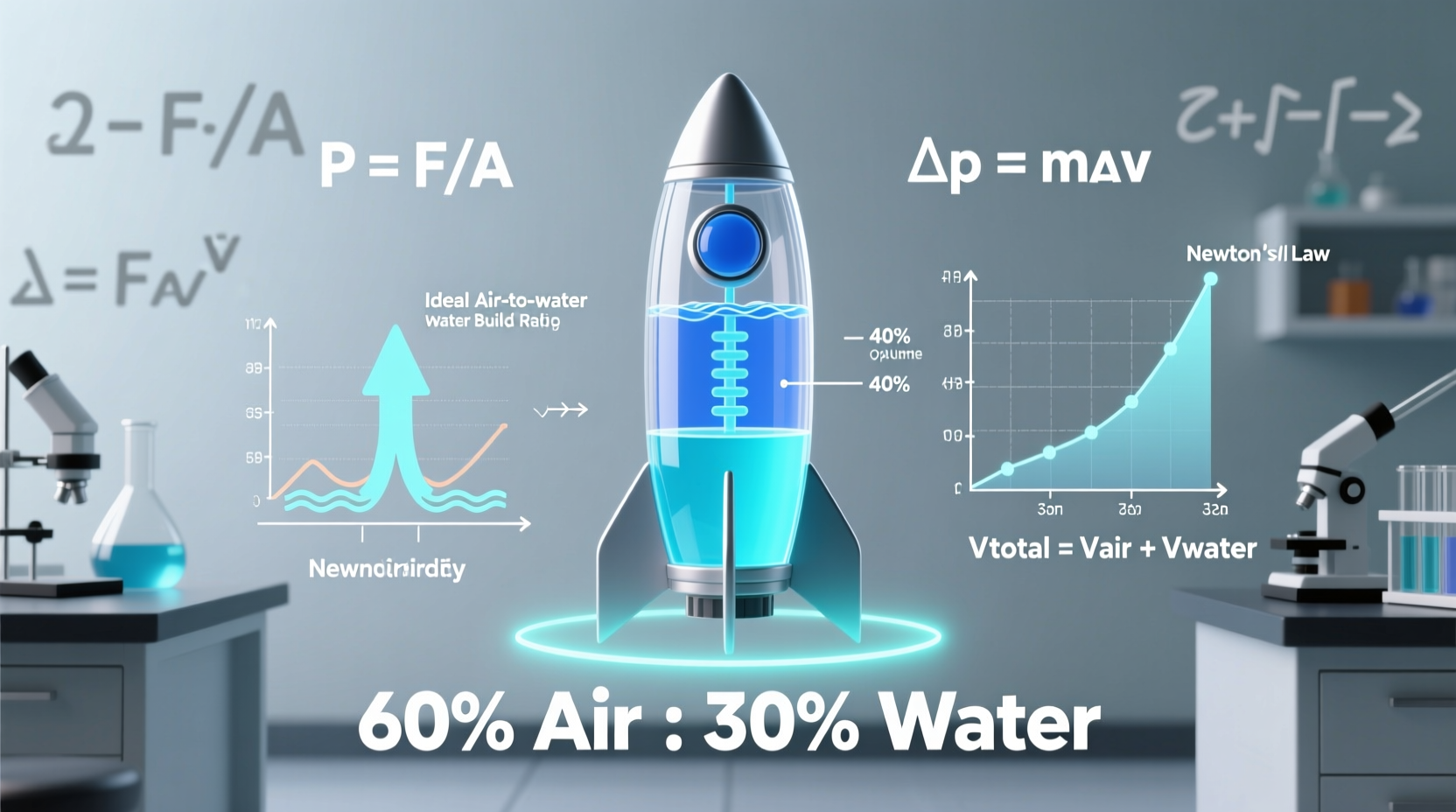

Understanding the Ideal Air-to-Water Ratio

The air-to-water ratio refers to the volume proportion of compressed air and liquid water inside the rocket chamber before launch. It’s typically expressed as a percentage of the total bottle volume occupied by water, with the remainder being air.

While many beginners fill bottles halfway, research and empirical data show that the ideal fill level is usually between **one-third and two-fifths** of the total capacity. For a standard 2-liter bottle, this translates to approximately **650–800 mL of water**, leaving 1.2–1.35 L for pressurized air at 60–90 psi.

This range maximizes both thrust duration and acceleration. Water provides high-density reaction mass, while sufficient air volume ensures prolonged pressure during expulsion. Once all water is ejected, thrust stops abruptly—even if air remains—because air alone has too little mass to generate meaningful thrust.

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Your Optimal Ratio

Finding your rocket’s peak performance isn’t guesswork—it’s a repeatable process grounded in controlled experimentation. Follow this timeline to determine the best air-to-water configuration for your setup.

- Standardize Equipment: Use the same pump, launch pad, bottle type (e.g., 2L PET), and nozzle size throughout testing.

- Select Test Points: Choose five water volumes: 500 mL, 700 mL, 800 mL, 900 mL, and 1100 mL.

- Pressurize Consistently: Pump each trial to exactly 80 psi using a calibrated gauge.

- Launch Vertically: Ensure launches are as vertical as possible to minimize drag variations.

- Measure Altitude: Use an inclinometer, altimeter app, or video analysis to estimate apogee.

- Repeat Each Trial: Conduct three launches per volume and average results.

- Analyze Data: Plot altitude vs. water volume to identify the performance peak.

This method isolates the effect of water volume while controlling other variables. Most teams find their optimum near 700–800 mL, but slight shifts occur based on nozzle diameter, rocket weight, and aerodynamic design.

Performance Comparison by Fill Level

The table below summarizes typical results from standardized tests using a 2L bottle, 80 psi, and a 22 mm nozzle.

| Water Volume (mL) | % Fill | Air Volume (L) | Average Apogee (ft) | Thrust Duration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 25% | 1.5 | 120 | 0.35 |

| 700 | 35% | 1.3 | 185 | 0.52 |

| 800 | 40% | 1.2 | 195 | 0.58 |

| 900 | 45% | 1.1 | 170 | 0.63 |

| 1100 | 55% | 0.9 | 110 | 0.71 |

Note how performance peaks at 800 mL despite longer thrust duration at higher fills. Excess water increases initial mass, reducing acceleration and increasing drag losses early in flight.

Real-World Case Study: The Pine Ridge Middle School Rocket Challenge

In 2023, Pine Ridge Middle School competed in a regional STEM rocketry contest. Their first prototype used a 50/50 water-air split and reached only 130 feet. After studying propulsion theory, students hypothesized that excess water was limiting acceleration.

They conducted a series of seven test launches varying water volume from 600 to 950 mL. Using smartphone barometric altimeters and ground-based angle tracking, they found peak performance at 780 mL—just under 40% fill. With refined fins and a streamlined nose cone, their final launch soared to 192 feet, earning them second place.

“We thought more water meant more power,” said team lead Mia Tran. “But once we saw the data, it made sense—balance matters more than quantity.”

Advanced Considerations: Temperature, Nozzle Size, and Bottle Strength

While the air-to-water ratio is foundational, secondary factors influence optimal performance:

- Nozzle Diameter: Larger nozzles increase mass flow rate but shorten thrust duration. Smaller nozzles extend burn time but may limit peak thrust. A 21–22 mm nozzle (standard bottle neck) often works best for 2L designs.

- Ambient Temperature: Warmer air expands more, increasing pressure slightly. However, temperature effects are minor below 100 psi.

- Bottle Integrity: Never exceed 100 psi with standard PET bottles. Overpressurization risks catastrophic failure. Always use safety goggles and remote release mechanisms.

Checklist for Maximum Water Rocket Performance

Before each launch day, verify the following:

- ✅ Use a pressure-rated PET bottle (no cracks or deformities)

- ✅ Fill with 35–40% water by volume (e.g., 700–800 mL in 2L bottle)

- ✅ Pressurize to 75–90 psi using a reliable gauge

- ✅ Confirm secure nozzle seal and upright launch alignment

- ✅ Deploy from a stable, flat launch platform

- ✅ Measure results consistently across trials

- ✅ Record environmental conditions (wind, temp, humidity)

Frequently Asked Questions

Does salt water improve thrust?

No. Salt water is denser, but the marginal increase in reaction mass is offset by increased corrosion risk and minimal performance gain. Stick to fresh water.

Can I use compressed nitrogen instead of air?

Theoretically, yes—but practically, no. Nitrogen behaves similarly to air at these pressures and offers negligible benefit. Compressed air from a bicycle pump or compressor is safe, accessible, and effective.

Why does my rocket tumble after launch?

Tumbling indicates poor stability, not water ratio issues. Ensure your center of pressure is behind the center of mass. Add lightweight fins near the base or shift weight forward with a small nose weight.

Conclusion: Launch Smarter, Not Harder

Maximizing water rocket performance isn’t about brute force—it’s about precision. The ideal air-to-water ratio leverages physics to convert stored pressure into sustained, efficient thrust. Through careful calculation, controlled testing, and attention to detail, you can transform a simple plastic bottle into a high-flying marvel of amateur engineering.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?