Completing a science project can be one of the most rewarding academic experiences for students. It fosters curiosity, develops critical thinking, and strengthens problem-solving skills. However, without proper planning and execution, even the most promising ideas can fall short. Success lies not in complexity, but in clarity, consistency, and methodical effort. This guide walks through every phase—from initial brainstorming to final presentation—with practical strategies to ensure your project stands out.

1. Choose a Focused and Testable Question

The foundation of any strong science project is a clear, specific question that can be investigated through experimentation. Avoid broad topics like “How does pollution affect the environment?” Instead, narrow it down: “How does nitrogen runoff affect algae growth in freshwater samples?” A well-defined question sets the stage for a manageable and meaningful investigation.

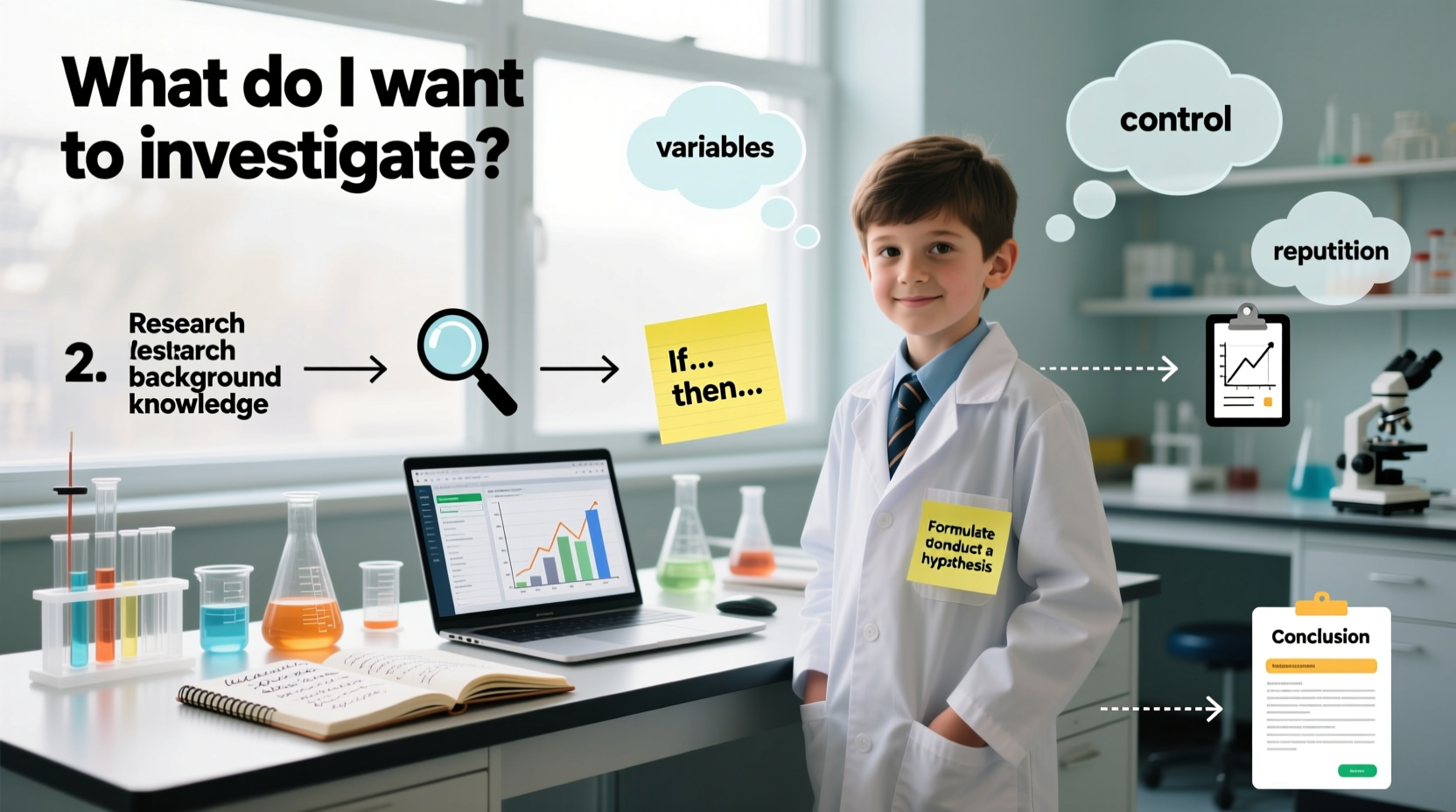

Begin by exploring areas of personal interest—biology, chemistry, physics, environmental science, or engineering. Then, conduct preliminary research to understand what’s already known. Use reputable sources such as scientific journals, educational websites, and textbooks. This helps you identify gaps or variations worth exploring.

2. Design a Controlled Experiment

Once you have a question, design an experiment that isolates one variable—the independent variable—while keeping all others constant. For example, if testing plant growth under different light colors, the light color is your independent variable; factors like soil type, water amount, and container size must remain consistent.

Your experiment should include:

- A control group (baseline for comparison)

- An experimental group (where the variable changes)

- Repeated trials (to ensure reliability)

- Clear measurement methods (e.g., millimeters of growth, seconds to react, pH levels)

“Good science isn’t about getting the ‘right’ answer—it’s about asking the right questions and designing experiments that yield trustworthy data.” — Dr. Linda Perez, Science Education Coordinator, National STEM Initiative

Key Components of Experimental Design

| Element | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | What you change | Type of fertilizer used |

| Dependent Variable | What you measure | Height of plant after 14 days |

| Controlled Variables | Factors kept constant | Light exposure, water volume, pot size |

| Hypothesis | Predicted outcome | “Plants with organic fertilizer will grow taller than those with synthetic.” |

3. Gather Materials and Conduct the Experiment

Prepare a detailed materials list before beginning. Include quantities, specifications, and safety equipment if needed (e.g., gloves, goggles). Source materials early—some items may require time to order or prepare.

When conducting the experiment:

- Follow your procedure exactly each time.

- Record observations immediately and objectively.

- Take notes on unexpected events (e.g., temperature fluctuations, equipment issues).

- Repeat trials at least three times for reliable data.

Data collection should be organized from day one. Use tables or spreadsheets to log measurements consistently. Label entries clearly with dates, trial numbers, and conditions.

4. Analyze Data and Draw Conclusions

Raw data alone doesn’t tell the full story. Organize it using charts, graphs, or averages to reveal patterns. Bar graphs work well for comparing groups; line graphs show trends over time.

Ask: Does the data support your hypothesis? Why or why not? Be honest—even negative results are valuable. They help refine understanding and suggest new questions.

For instance, if your hypothesis predicted faster mold growth in warm environments but results showed no significant difference, consider possible explanations: Was humidity uncontrolled? Did sample sizes vary?

Mini Case Study: The Moldy Bread Experiment

Sophia, a 7th grader, wanted to know how storage conditions affect mold growth on bread. She placed identical slices in four environments: refrigerator, pantry, sealed container, and open air. Each day for ten days, she photographed the slices and recorded visible mold coverage.

Her data showed the fastest mold growth in the open-air slice, followed by the pantry. The refrigerator and sealed container had minimal growth. While her hypothesis was correct, she noticed the sealed container developed condensation—a factor she hadn’t accounted for. In her conclusion, she recommended future studies monitor moisture levels inside containers.

This attention to detail elevated her project from basic observation to thoughtful analysis.

5. Present Your Findings Effectively

A successful science project isn’t just about doing the work—it’s about communicating it clearly. Whether presenting at a school fair or submitting a report, structure your presentation logically:

- Title: Clear and descriptive (e.g., “The Impact of Caffeine Concentration on Daphnia Heart Rate”)

- Introduction: Explain the topic, question, and why it matters

- Hypothesis: State your prediction and reasoning

- Materials & Methods: Detail how you conducted the experiment

- Results: Display data with visuals (graphs, photos, tables)

- Conclusion: Summarize findings, discuss limitations, and suggest next steps

Keep text concise on display boards. Use bullet points, large fonts, and high-contrast colors. Practice explaining your project aloud in under three minutes—this builds confidence and clarity.

Project Preparation Checklist

- ☐ Finalized research question

- ☐ Completed background research

- ☐ Designed controlled experiment

- ☐ Collected and recorded data from multiple trials

- ☐ Created graphs or visual representations of results

- ☐ Written conclusion with interpretation and limitations

- ☐ Prepared display board or digital presentation

- ☐ Practiced oral explanation

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should a science project take?

Start at least 4–6 weeks before the deadline. This allows time for research, repeated trials, troubleshooting, and polishing your presentation. Complex projects may require more time, especially if growing plants or monitoring slow processes.

What if my results don’t match my hypothesis?

That’s perfectly acceptable—and common in real science. What matters is how you interpret the results. Discuss possible reasons, errors, or external factors. Demonstrating analytical thinking often impresses judges more than confirming a guess.

Can I work with a partner?

Yes, many schools allow team projects, but ensure responsibilities are balanced. Each member should contribute equally to research, experimentation, and presentation. Clearly define roles early to avoid conflicts later.

Final Thoughts

A successful science project doesn’t require advanced equipment or a groundbreaking discovery. It requires curiosity, organization, and persistence. By following a structured approach—from choosing a focused question to presenting findings with clarity—you build not only a strong project but also lifelong scientific habits.

Every great scientist started with a simple question and the courage to test it. Now it’s your turn. Begin with a single idea, stay committed through challenges, and share what you learn with confidence.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?