The tomato is now a cornerstone of global cuisine—essential in Italian sauces, Mexican salsas, Middle Eastern salads, and American summer gardens. Yet few realize that this vibrant fruit, so deeply embedded in culinary traditions worldwide, originated thousands of miles from the kitchens that celebrate it most. Understanding where the tomato first grew reveals not just a botanical history, but a story of human migration, colonial exchange, and agricultural transformation. Its journey from an obscure wild plant in South America to a dietary staple across continents reshaped food cultures and continues to influence farming and flavor today.

For home cooks, chefs, and gardeners alike, knowing the roots of the tomato offers more than trivia—it informs better selection, cultivation, and appreciation of its varieties. The flavors, colors, and textures we associate with tomatoes today are the result of centuries of adaptation and breeding, beginning in the Andean region long before Europeans encountered them. This article explores the true birthplace of the tomato, traces its path into global kitchens, and explains how its origin still influences how we grow and use it.

Definition & Overview

The tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) is a flowering plant in the nightshade family (Solanaceae), which includes potatoes, eggplants, and peppers. Botanically classified as a berry, the tomato develops from the ovary of a flower and contains seeds surrounded by juicy pulp. Despite frequent classification as a vegetable in culinary contexts—especially due to a late 19th-century U.S. Supreme Court ruling for tariff purposes—the tomato is scientifically a fruit.

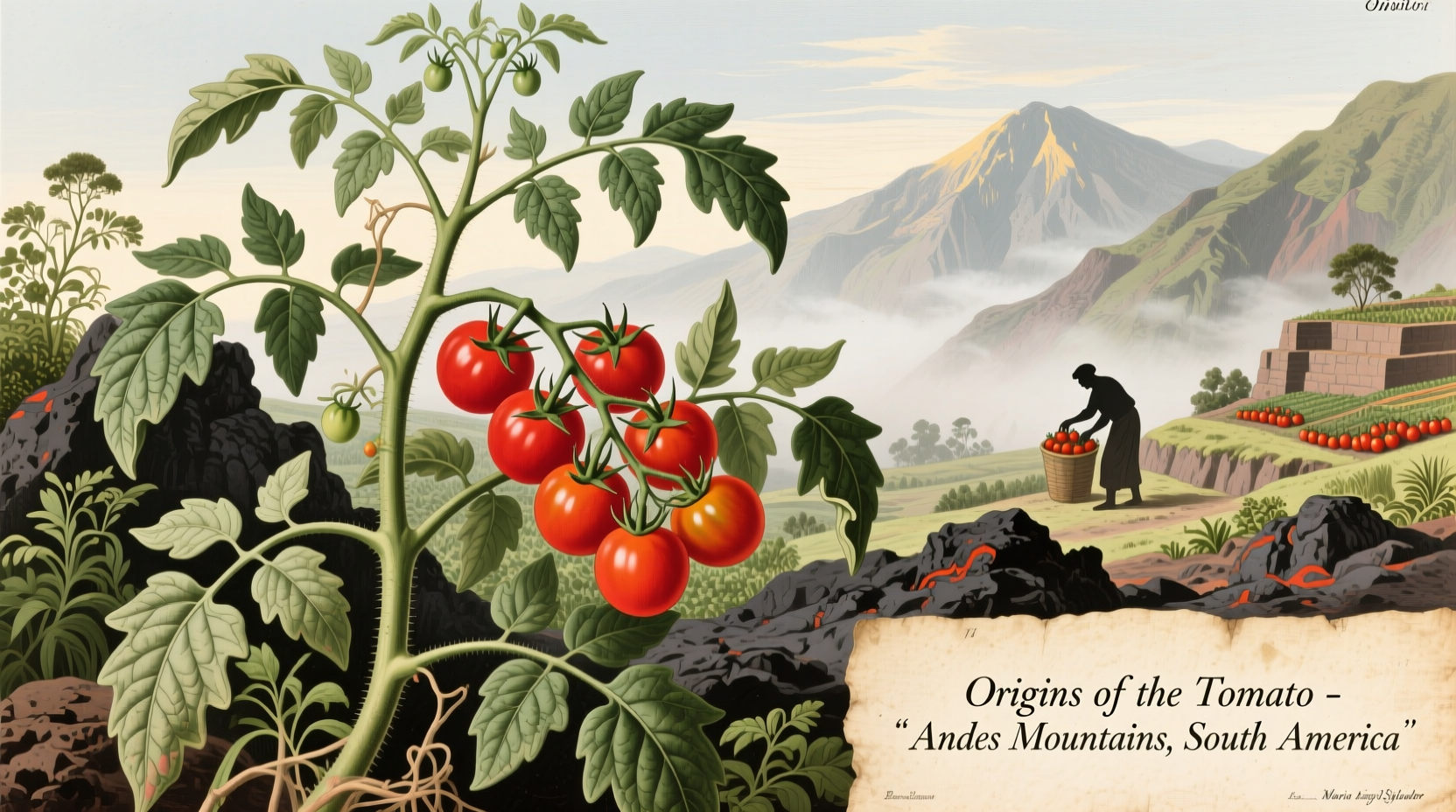

The earliest cultivated forms of the tomato emerged in western South America, specifically in the region spanning modern-day Peru, Ecuador, and northern Chile. Wild ancestors of the modern tomato, such as Solanum pimpinellifolium, still grow in these areas, producing small, pea-sized red fruits with intense flavor. These ancestral plants were gradually domesticated by indigenous peoples over thousands of years, selected for larger size, juiciness, and palatability.

By the time Spanish explorers arrived in the Americas in the early 16th century, Mesoamerican civilizations like the Aztecs had already developed advanced cultivation techniques and incorporated domesticated tomatoes—known as tomatl in Nahuatl—into their diets. The word “tomato” itself derives from this indigenous term. From there, the plant was introduced to Europe, where it faced suspicion before eventually becoming central to Mediterranean cooking.

Key Characteristics

The characteristics of the tomato vary widely by variety, but several traits define the species as a whole:

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Flavor Profile | Balanced sweetness and acidity; ranges from bright and tangy to rich and umami-laden depending on ripeness and cultivar. |

| Aroma | Grassy, green, and slightly floral when raw; deeper, roasted notes when cooked. |

| Color & Form | Most commonly red when ripe, but also yellow, orange, green, purple, black, or striped; shapes include round, oblong, pear, and plum. |

| Texture | Juicy with firm gel surrounding seeds; flesh can be meaty (in paste types) or watery (in slicers). |

| Culinary Function | Used as a base for sauces, soups, stews; eaten fresh in salads; roasted, grilled, or preserved. |

| Shelf Life | 3–7 days at room temperature when ripe; up to two weeks refrigerated (though flavor degrades). |

| Heat Sensitivity | Not spicy; contains no capsaicin. Heat during cooking enhances flavor complexity. |

Practical Usage: How to Use Tomatoes in Cooking

The versatility of the tomato stems directly from its diverse forms and stages of ripeness. Understanding how to match type to technique elevates everyday dishes.

In home kitchens, ripe red tomatoes shine in raw applications. A classic Caprese salad relies on thick slices of beefsteak tomato layered with fresh mozzarella and basil, dressed simply with olive oil and sea salt. The acidity cuts through the cheese’s richness, while the juice pools into the oil, creating a natural dressing. For salsas, Roma or plum tomatoes are preferred—they’re less watery, holding their shape and delivering concentrated flavor.

Cooking transforms tomatoes dramatically. When simmered into sauces, their natural pectin breaks down, thickening the liquid while acids mellow. San Marzano tomatoes, grown in volcanic soil near Mount Vesuvius, are prized for their low seed count, sweet taste, and dense flesh—ideal for slow-cooked Neapolitan ragùs. Canned whole peeled tomatoes, especially those packed in juice or puree without calcium chloride, offer year-round access to this quality.

Roasting intensifies sweetness and deepens color. Halved cherry tomatoes roasted at 400°F (200°C) with garlic and thyme become jammy and aromatic—perfect for spreading on toast or folding into pasta. Sun-drying removes moisture further, concentrating sugars and making them ideal for antipasti platters or rehydrating in warm olive oil for dressings.

Pro Tip: Never refrigerate unripe tomatoes. Cold temperatures halt ethylene production, preventing full ripening and diminishing flavor compounds. Store at room temperature, stem-side down, until fully colored and slightly soft to touch.

Variants & Types

Modern breeding and heirloom preservation have yielded hundreds of tomato varieties, each suited to specific uses. Recognizing the main categories helps in selecting the right type for any recipe.

- Beefsteak: Large, ribbed fruits with thick flesh and large seed cavities. Best for slicing and sandwiches. Examples: Brandywine, Cherokee Purple.

- Globe / Round Slicing: Uniformly round, medium to large. Common in supermarkets. Good all-purpose use. Example: Celebrity, Better Boy.

- Roma / Plum: Oval-shaped, fewer seeds, dense flesh. Ideal for sauces and canning. Example: San Marzano, Amish Paste.

- Cherry: Small, grape-sized, very juicy. Perfect for snacking, roasting, or salads. Example: Sungold, Black Cherry.

- Heirloom: Open-pollinated varieties passed down generations. Often irregular in shape and color. Valued for complex flavor. Example: Green Zebra, German Johnson.

- Currant: Smallest type, about the size of a blueberry. Extremely sweet and prolific. Used in gourmet garnishes. Example: Red Currant.

- Greenhouse / Hydroponic: Commercially grown year-round under controlled conditions. Often uniform but less flavorful. Common in winter markets.

Each variant reflects adaptations rooted in the original gene pool of Andean wild tomatoes. For instance, the high sugar content in cherry types echoes the intense flavor of S. pimpinellifolium, while disease resistance in modern hybrids often comes from introgression of wild relatives.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

The tomato is frequently confused with other nightshades or red fruits. Clarifying differences ensures proper usage in recipes.

| Ingredient | Key Differences from Tomato |

|---|---|

| Red Bell Pepper | Sweeter, crispier texture; no internal gel or seeds suspended in liquid. Belongs to Capsicum genus; not acidic like tomato. |

| Pomegranate | Arils are tart and crunchy; juice is astringent. Not used as a base ingredient but as a condiment or garnish. |

| Gooseberry Tomato (Cape Gooseberry / Physalis) | Encased in a papery husk; belongs to same family but different genus. Tangy-sweet, tropical profile. |

| Wolf Peach (Solanum umbelliferum) | Wild relative, toxic when green. Not edible. Sometimes mistaken for wild tomato. |

| Tomatillo | Firm, green, tart fruit used in Mexican verde sauces. Covered in husk; never turns red when ripe. |

One common misconception is that tomatillos are \"green tomatoes.\" They are not. Green tomatoes refer to unripe regular tomatoes, which can be fried or pickled but lack the citrusy tartness of tomatillos.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Where did the tomato originally grow?

The tomato was first domesticated in western South America, particularly in the Andes region encompassing parts of modern Peru, Ecuador, and Chile. Wild ancestors still grow there today.

Were tomatoes always eaten?

No. In Europe, tomatoes were initially grown as ornamental plants due to fears they were poisonous—stemming from their membership in the nightshade family. Widespread culinary adoption didn’t occur until the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly in southern Italy and Spain.

Can I grow tomatoes from store-bought fruit?

You can, but success depends on the type. Hybrid tomatoes (like most supermarket varieties) may not grow true to type. Heirloom or open-pollinated tomatoes yield more predictable results. Ferment the seeds for 3–5 days to remove germination inhibitors before drying and planting.

What’s the best way to preserve tomatoes?

Options include canning (water bath or pressure), sun-drying, freezing (blanched or puréed), or turning into sauce or paste. Olive oil preservation is traditional but requires strict pH control to prevent botulism risk.

Are greenhouse tomatoes inferior?

Often, yes—especially in flavor. Controlled environments prioritize yield and shelf life over aroma and sugar development. However, advanced hydroponic systems using supplemental lighting and nutrient tuning are closing the gap, particularly in winter months when field-grown options are unavailable.

Why do some tomatoes taste bland?

Commercial breeding has favored traits like crack-resistance, uniform color, and long shelf life over flavor. A 2012 study published in *Science* identified a genetic mutation in many modern varieties that disables a sugar-transport protein, reducing sweetness. Heirlooms and locally grown seasonal tomatoes typically offer superior taste.

Storage Checklist:

- Store ripe tomatoes at room temperature, away from direct sunlight.

- Use within 5–7 days for peak flavor.

- If overripe, cook immediately or freeze for later sauce-making.

- Never wash until ready to use—moisture accelerates spoilage.

- Keep stems intact as long as possible to reduce mold entry.

“The flavor of a truly ripe tomato, straight from the vine in August, is one of the great pleasures of the growing season. It’s not just taste—it’s memory, scent, texture, and light all combined.” — Alice Waters, chef and founder of Chez Panisse

Summary & Key Takeaways

The tomato’s journey began in the Andean highlands of South America, where wild ancestors were first gathered and later domesticated by indigenous farmers. From small red berries on sprawling vines, selective breeding produced the diverse forms we know today. Transplanted to Europe via Spanish conquest, the tomato overcame initial suspicion to become foundational in Mediterranean cuisine, then spread globally through trade and migration.

Understanding the tomato’s origin informs how we grow, select, and prepare it. Varietal diversity—from tiny currants to massive heirlooms—reflects millennia of human interaction with this plant. Flavor, texture, and suitability for specific dishes depend heavily on type and ripeness, making informed choices essential for quality cooking.

Whether you're picking cherry tomatoes from a backyard garden or choosing canned San Marzanos for Sunday sauce, recognizing the deep agricultural and cultural roots of the tomato enriches every bite. Its story is a reminder that even the most ordinary ingredients carry extraordinary histories.

Call to Action: This summer, try growing an heirloom tomato variety like Brandywine or Green Zebra. Observe how its flavor differs from supermarket types. Taste the legacy of ancient Andean fields in your own kitchen.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?