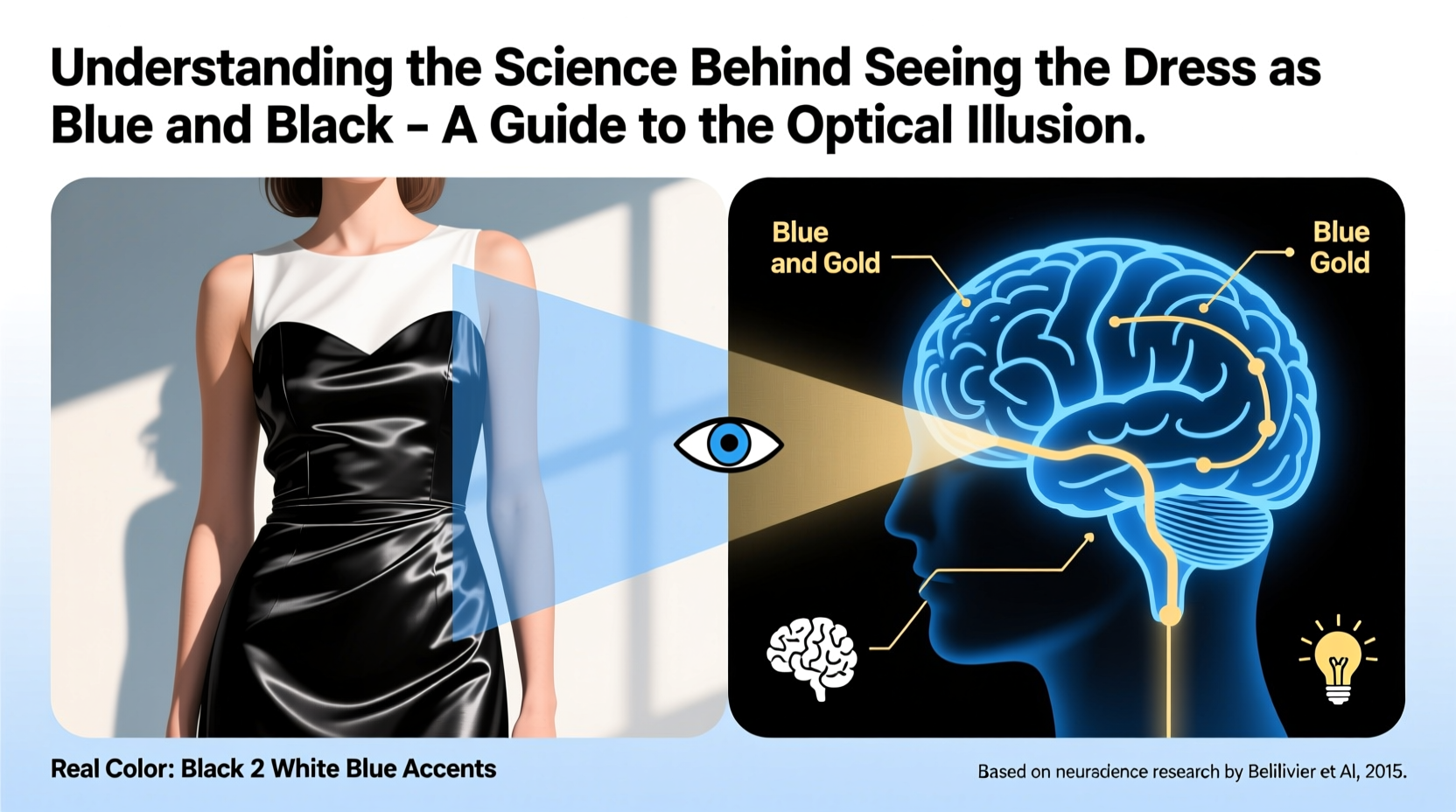

In 2015, a single photograph of a dress sparked a global debate: was it blue and black or white and gold? What began as a casual conversation between friends quickly exploded into one of the most viral moments in internet history. Scientists, psychologists, and curious individuals around the world weighed in, not just to settle the color dispute, but to explore the deeper mechanisms of human perception. The phenomenon revealed something profound—our eyes don’t simply record reality; they interpret it based on context, lighting, and individual brain processing. This article unpacks the neuroscience and psychology behind the illusion, explaining why reasonable people can look at the same image and see entirely different colors.

The Viral Moment That Changed Internet Culture

The dress photo, originally posted by Cecilia Bleasdale in a private Facebook group, showed a simple lace gown under ambiguous lighting. When her mother insisted it was white and gold while Cecilia saw blue and black, confusion turned into curiosity. Within hours, the post went public and spread across social media platforms. Major news outlets picked up the story, with celebrities and scientists offering their takes. Polls showed a near-even split in perception—roughly half the population saw white and gold, the other half blue and black.

This wasn’t just a quirky disagreement. It highlighted a fundamental truth about visual processing: perception is not objective. Two people can view identical stimuli and experience completely different realities. The dress became a cultural touchstone, illustrating how subjective experience shapes our understanding of the world—even when it comes to something as seemingly straightforward as color.

How the Human Visual System Processes Color

To understand the dress illusion, it’s essential to grasp how the brain interprets color. The human eye contains photoreceptors called cones that detect red, green, and blue light. However, raw signals from these receptors are only the beginning. The brain must then make sense of this data in context—especially under varying lighting conditions.

A key process involved is color constancy. This allows us to perceive an object’s color as stable even when illumination changes. For example, a red apple looks red whether viewed in sunlight, shade, or indoor lighting. The brain automatically adjusts for the ambient light, subtracting its influence to estimate the “true” color of objects.

In the case of the dress, the photograph lacked clear cues about the light source. Was it lit by cool daylight or warm indoor lighting? Depending on how the brain interpreted the lighting, viewers adjusted their perception accordingly:

- If the brain assumed the dress was in shadow (cooler light), it would compensate by removing blue tones, making the dress appear warmer—white and gold.

- If the brain assumed bright overhead lighting (warmer light), it would subtract yellow tones, leading to a perception of blue and black.

This unconscious correction is what caused the dramatic divergence in perception.

Neurological and Psychological Factors at Play

Research conducted after the viral event revealed that individual differences in circadian rhythm and visual exposure may influence how people perceive the dress. A study published in Current Biology found that people who typically wake up early (morning types) were more likely to see the dress as white and gold, possibly because their brains are accustomed to brighter, cooler morning light and thus assume the scene is illuminated by daylight.

Conversely, those who stay up late (evening types) tended to interpret the lighting as artificial and warm, leading them to perceive the dress as blue and black. This suggests that lifetime exposure to certain lighting conditions trains the brain to make specific assumptions about illumination.

“Perception is a kind of unconscious inference. The brain uses prior experience to guess what’s out there.” — Dr. Beau Lotto, Neuroscientist and Vision Researcher

Another factor is cognitive expectation. The brain constantly predicts what it will see based on past experiences. If someone has frequently seen brides in white dresses, their brain might be primed to interpret ambiguous gowns as white—even when evidence contradicts this.

Step-by-Step: How Your Brain Decides What Color You See

The process of interpreting the dress happens rapidly and unconsciously. Here’s a breakdown of the sequence:

- Light enters the eye: Photons from the screen hit the retina, activating cone cells sensitive to different wavelengths.

- Signal transmission: Neural signals travel from the retina to the visual cortex via the optic nerve.

- Context analysis: The brain evaluates surrounding pixels and attempts to determine the light source’s color temperature.

- Color correction: Based on assumptions about lighting, the brain adjusts perceived hues using color constancy mechanisms.

- Object recognition: The corrected colors are matched to known objects—in this case, a dress—leading to a final perceptual judgment.

Crucially, steps three and four rely on assumptions. When contextual clues are missing or conflicting, different brains make different guesses—resulting in divergent perceptions.

Do’s and Don’ts When Interpreting Visual Illusions

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Consider the role of lighting and contrast in shaping perception | Assume your perception is objectively correct |

| Test illusions in different environments (e.g., bright vs. dim rooms) | Dismiss others’ experiences as “wrong” or “imagined” |

| Use illusions to explore how your brain fills in sensory gaps | Overgeneralize findings to all visual tasks without evidence |

| Consult scientific studies for validated explanations | Rely solely on intuition to explain complex perceptual phenomena |

Real Example: A Classroom Experiment

In a university psychology course, Professor Linda Reyes used the dress illusion as a teaching tool. She projected the image onto a screen and asked students to vote anonymously on the colors they saw. Out of 47 students, 26 reported white and gold, 19 saw blue and black, and 2 were uncertain. After discussing color constancy and neural processing, she altered the classroom lighting—first turning off overhead fluorescents, then using warm-toned lamps.

Remarkably, several students reported shifts in perception. One student who initially saw white and gold said, “Now it looks distinctly blue. I didn’t think my brain could change like that.” The exercise demonstrated not only the power of context but also the malleability of perception—a lesson far more impactful than any textbook explanation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was the dress actually blue and black?

Yes. The physical dress, manufactured by Roman Originals, is officially blue and black. Photographs taken under controlled lighting confirm this. However, the viral image’s ambiguity allowed for alternative interpretations due to perceptual processing, not camera error.

Can you train yourself to see both versions?

Some people can switch between perceptions by focusing on different parts of the image or changing their viewing environment. Staring at a gray area before looking at the dress can also reset color adaptation, temporarily allowing a shift in perception. However, most people have a dominant interpretation that remains stable over time.

Are there other illusions like this?

Yes. Similar effects include the “Yanni or Laurel” audio illusion and Rubin’s vase, where figure-ground perception flips between two interpretations. These all demonstrate how the brain resolves ambiguity using context and expectation.

Conclusion: Embracing the Subjectivity of Perception

The dress illusion was never really about fashion—it was a window into the mind. It reminded millions that perception is constructed, not recorded. Two people can witness the same event and walk away with different truths, not because one is wrong, but because the brain is designed to interpret, not mirror, reality.

Understanding this has broader implications: in communication, design, and even conflict resolution, recognizing perceptual differences fosters empathy and clarity. The next time you encounter a disagreement over something “obvious,” consider whether it’s a difference in facts—or in how each person sees the world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?