Celery is one of the most ubiquitous vegetables in Western cuisine, often relegated to the role of background filler in mirepoix or crudité platters. Yet beneath its crisp, pale-green exterior lies a sophisticated anatomical structure that directly influences its texture, flavor release, storage longevity, and culinary performance. Understanding the physical composition of a celery stalk is not merely botanical curiosity—it’s a practical necessity for precise knife work, efficient flavor extraction, and maximizing both taste and nutrition in cooking. From the fibrous vascular bundles to the water-rich parenchyma cells, each component plays a distinct role in how celery behaves when chopped, cooked, or eaten raw. This detailed exploration breaks down the celery stalk at a structural level, revealing why it responds the way it does in soups, stir-fries, salads, and stocks—and how chefs and home cooks alike can use this knowledge to elevate their results.

Definition & Overview

Celery (Apium graveolens var. dulce) is a marshland plant species cultivated as a vegetable, prized primarily for its long, ribbed petioles—commonly referred to as \"stalks.\" Though often mistaken for a stem, the edible portion of celery is technically the petiole, or leaf stalk, which supports the compound leaves of the plant. Commercially grown celery is selected for elongated, tightly packed petioles that grow upward from a central crown, forming what we recognize as a \"bunch\" or \"head\" of celery.

Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, celery has been used since antiquity—not only as food but also as medicine and ceremonial ornament. Modern culinary celery is a descendant of wild celery (smaller, more aromatic, and bitter), selectively bred over centuries for milder flavor, higher water content, and crunchier texture. It belongs to the Apiaceae family, which includes carrots, parsley, fennel, and dill, many of which share aromatic compounds like phthalides and terpenes.

The standard grocery-store celery—bright green, rigid, and juicy—is just one form. Heirloom varieties include golden (blanched) celery, red-streaked types, and leaf celery, each with unique structural and flavor profiles. However, the common green Pascal-type celery remains the benchmark for structural analysis due to its widespread use and standardized morphology.

Key Characteristics of a Celery Stalk

The physical attributes of a celery stalk are not uniform—they vary by region of the stalk, maturity, and growing conditions. Below is a breakdown of its defining characteristics:

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Texture | Crisp and crunchy when fresh; becomes stringy or limp when dehydrated. The crunch comes from turgor pressure in parenchyma cells and structural support from collenchyma tissue. |

| Flavor Profile | Mildly bitter, earthy, with herbal top notes. Contains volatile compounds like limonene and sedanenolide that contribute to its distinctive aroma. Less mature stalks are sweeter and less fibrous. |

| Aroma | Green, slightly peppery, with citrus undertones. Releases more fragrance when cut or crushed due to cell rupture and oxidation of essential oils. |

| Color | Variants range from pale green (blanched) to deep emerald. Color intensity correlates with chlorophyll content and exposure to sunlight. |

| Water Content | Approximately 95%, making it highly perishable but excellent for hydration and dilution in liquid-based dishes. |

| Culinary Function | Aromatic base (e.g., mirepoix), textural contrast (salads, crudités), thickening agent (when pureed), and natural flavor enhancer (umami via glutamates). |

| Shelf Life | 7–14 days refrigerated in high-humidity drawer. Degrades rapidly if exposed to air or warmth due to moisture loss and enzymatic browning. |

Anatomical Breakdown: The Layers of a Celery Stalk

To truly understand how celery behaves in cooking, one must examine its internal architecture. A cross-section reveals several distinct tissues, each serving a biological function that translates into culinary behavior.

1. Epidermis (Outer Skin)

The outermost layer is a thin, waxy epidermis that protects against water loss and pathogens. In culinary terms, this layer contributes to the initial resistance when biting into raw celery. While edible, it can be tough in older stalks and is sometimes peeled in fine dining applications—particularly in consommés or delicate purées where smoothness is paramount.

2. Collenchyma Tissue (Stringy Fibers)

Beneath the skin lie longitudinal strands of collenchyma cells—living, elongated cells with unevenly thickened walls that provide flexible structural support. These are the infamous \"strings\" that catch between teeth when eating celery raw. They run parallel to the length of the stalk and become more pronounced with age and poor growing conditions (e.g., drought stress).

These fibers are composed largely of cellulose and pectin, which partially break down during prolonged cooking. In braises or stocks, they soften and disintegrate, releasing gelatinous pectins that subtly thicken liquids. However, in quick sautés or raw applications, they remain intact and may benefit from removal—especially in tender dishes like cream soups or mousses.

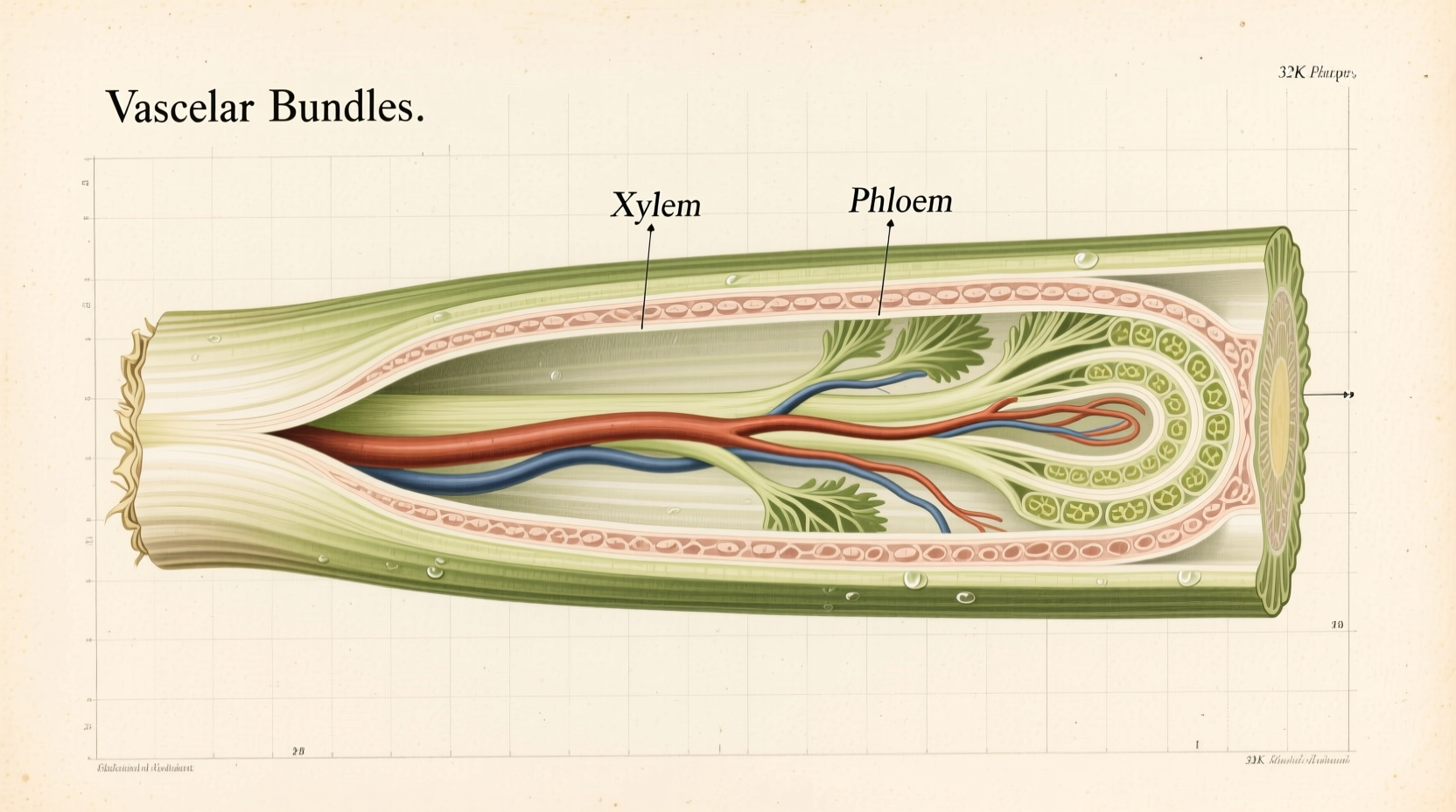

3. Vascular Bundles (Conducting Tissues)

Embedded within the collenchyma are vascular bundles containing xylem and phloem. The xylem transports water and minerals from roots to leaves; the phloem carries sugars produced by photosynthesis. These bundles appear as tiny dots or lines when viewed under magnification and are responsible for celery’s ability to “drink” colored water in science experiments.

Culinarily, these channels concentrate flavor compounds and nutrients. When celery is simmered, these vessels leach minerals, organic acids, and aromatic molecules into the broth. This is why even small amounts of celery contribute significantly to the depth of flavor in stocks and sauces.

4. Parenchyma Cells (The \"Flesh\")

Filling the interior are large, water-filled parenchyma cells. These make up the bulk of the stalk's volume and are responsible for its juiciness and mild sweetness. Rich in water-soluble nutrients—including vitamin K, potassium, and apigenin (a flavonoid with antioxidant properties)—these cells rupture easily when chewed or chopped, releasing liquid and volatile aromatics.

In cooking, the collapse of parenchyma cells affects texture: rapid heating causes steam buildup and potential splintering, while slow sweating allows gradual moisture release without breaking structure. This explains why celery added to a hot pan too quickly may sputter and lose integrity, whereas gently sweated celery retains shape and integrates smoothly into sauces.

5. Medullary Cavity (Central Hollow)

In mature stalks, especially the outer ribs, a central medullary cavity develops—a hollow core formed as inner cells degenerate. This reduces weight and increases flexibility in the growing plant. For cooks, this cavity can trap dirt and microbes, necessitating thorough washing. It also creates a natural conduit for flavor infusion: stuffing or marinating celery stalks allows seasonings to penetrate deeply.

Pro Tip: To clean stalks effectively, slice them in half lengthwise and use a small brush or your finger to scrub out the medullary cavity. Alternatively, soak in cold water with a splash of vinegar for 5–10 minutes to loosen debris.

Practical Usage: How Structure Influences Cooking Technique

Knowledge of celery’s anatomy directly informs better kitchen practice. The way you cut, cook, and combine celery should align with its structural strengths and weaknesses.

Knife Skills: Aligning Cuts with Fiber Direction

Because collenchyma fibers run longitudinally, slicing celery crosswise (perpendicular to the stalk) shortens the fibers, improving tenderness. For salads or garnishes, bias cuts (diagonal slices) increase surface area and visual appeal while maintaining bite-sized manageability.

In contrast, julienning or cutting long strips preserves fiber length, which can result in unpleasant stringiness unless the celery is cooked until very soft. If preparing raw celery sticks for dipping, consider scoring the inner curve lightly with a paring knife before bending—the stalk will snap cleanly along the scored line, removing tough fibers from the break point.

Sweating vs. Sautéing: Managing Moisture Release

When building flavor bases (like mirepoix, sofrito, or holy trinity), celery is typically diced and sweated slowly in fat over low heat. This technique allows parenchyma cells to release moisture gradually, concentrating flavors without browning. Rapid frying causes explosive water release, leading to spattering and uneven cooking.

For dishes requiring color and caramelization (e.g., roasted vegetable medleys), toss celery pieces in oil and roast at high heat (400°F/200°C). The dry environment promotes evaporation, concentrating sugars and enhancing nutty complexity.

Stocks and Broths: Maximizing Flavor Extraction

In bone broths and vegetable stocks, whole or halved stalks are preferred. The intact structure prevents over-extraction of bitter compounds while allowing steady diffusion of aromatic molecules. Remove after 45–60 minutes to avoid cloudiness and excessive bitterness.

For maximum yield, crush or bruise stalks before adding to stock. This ruptures cell walls and accelerates flavor release. Save trimmings (leaf bases, outer skins, root ends) in a freezer bag for homemade stock—rich in phthalides and mineral content.

Purees and Cream Soups: Achieving Smooth Texture

For silky-textured soups, remove strings before blending. One method: use a vegetable peeler to strip the outer layer from each stalk, starting at the base and pulling toward the tip. Alternatively, blanch stalks for 2 minutes, then shock in ice water—the heat loosens the epidermis, making peeling easier.

“Understanding plant anatomy transforms cooking from guesswork to precision. With celery, knowing where the fibers run and how cells hold water lets you control texture and flavor with intention.”

— Chef Elena Torres, Culinary Science Instructor, San Francisco School of Food Arts

Variants & Types of Celery

While Pascal celery dominates supermarkets, other forms offer different structural and flavor profiles:

- Pascal (Green) Celery: Tall, thick ribs with strong vertical fibers. High water content; best for raw eating, juicing, and mirepoix.

- Golden (Blanched) Celery: Grown covered to exclude light, resulting in pale yellow stalks. Milder, less fibrous, and more tender. Ideal for delicate soups and garnishes.

- Red Celery (e.g., ‘Red Venture’): Anthocyanin pigments give a crimson blush. Structural integrity similar to green types, but slightly sweeter and less bitter. Excellent for colorful salads.

- Leaf Celery (Smallage): Thin stalks with minimal parenchyma tissue but intense aroma. Used primarily for seasoning in Asian and Caribbean cuisines. Requires no peeling due to lack of prominent strings.

- Celeriac (Celery Root): Same species, but grown for its swollen hypocotyl (stem base). Dense, knobby structure; stores longer than stalks. Must be peeled deeply to remove coarse outer layers.

| Type | Fiber Density | Best Use | Storage Life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pascal (Green) | High | Raw applications, stocks | 10–14 days |

| Golden (Blanched) | Medium | Cream soups, fine dining | 7–10 days |

| Red | Medium-High | Salads, roasting | 10–12 days |

| Leaf Celery | Low | Seasoning, stir-fries | 5–7 days |

| Celeriac | N/A (root-like) | Roasting, mashing, shredding | 3–4 weeks (cool, dark) |

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Celery is frequently confused with related plants, but structural differences affect substitution viability.

- Fennel Bulb: Though bulbous and layered, fennel lacks longitudinal fibers. Its anise-like flavor dominates; texture is crisper and more watery. Not interchangeable in mirepoix unless flavor profile allows.

- Bunching Onion / Scallion: Hollow, cylindrical stalks with concentric layers. No collenchyma strings. Milder, onion-forward taste. Can replace celery in salads but not as a neutral aromatic base.

- Rhubarb: Often mistaken visually, but rhubarb is a true stem with dense vascular bundles and high oxalic acid. Edible only when cooked with sugar; structurally tougher and more fibrous than celery.

- Cardoon: A thistle relative with thick, woolly stalks. Requires extensive trimming and blanching. Fibers are coarser and more numerous than celery. Flavor is artichoke-like, not herbal.

Practical Tips & FAQs

How do I remove celery strings effectively?

Use a vegetable peeler or paring knife to pull off the outer layer from base to tip. Start at the cut end and grip the protruding fiber bundle—pull downward firmly. Repeat on all sides if needed. Blanching first makes peeling easier.

Can I eat celery leaves?

Absolutely. Leaves are more flavorful than stalks, with higher concentrations of essential oils and nutrients. Chop finely and use as herb in dressings, stuffings, or pesto. They wilt quickly, so store separately in a damp paper towel.

Why does celery become limp in the fridge?

Loss of turgor pressure due to dehydration. Cell walls collapse when water diffuses out. Revive by soaking in ice water for 20–30 minutes. Prevent by storing in a sealed container with a damp cloth or in water.

Is there a difference between inner and outer stalks?

Yes. Inner stalks (closer to the heart) are younger, more tender, and less fibrous—ideal for raw consumption. Outer stalks are larger, woodier, and better suited for cooking. Reserve outer ribs for stocks and stews.

Can celery be frozen?

Yes, but texture changes dramatically. Freezing ruptures parenchyma cells, causing mushiness upon thawing. Best for cooked applications like soups and sauces. Blanch first to preserve color and deactivate enzymes.

What are the health implications of celery’s structure?

The insoluble fiber (from collenchyma) supports digestive health. The high water content aids hydration. Apigenin, concentrated in parenchyma cells, has been studied for anti-inflammatory properties. However, some individuals may experience allergic reactions to proteins in celery, particularly when raw.

Storage Checklist:

✔ Store upright in a container with 1–2 inches of water (like flowers)

✔ Cover loosely with a plastic bag to retain humidity

✔ Change water every 2–3 days

✔ Use inner stalks first; outer ones last

✔ Freeze only for cooking use

Summary & Key Takeaways

The celery stalk is far more than a crunchy snack or soup add-in—it is a biologically engineered structure optimized for support, transport, and survival, all of which translate into tangible culinary outcomes. Recognizing its five main components—epidermis, collenchyma fibers, vascular bundles, parenchyma cells, and medullary cavity—empowers cooks to manipulate texture, enhance flavor extraction, and prevent common pitfalls like stringiness or sogginess.

Different celery varieties serve distinct purposes: Pascal for versatility, golden for delicacy, leaf type for potency, and celeriac for storage and heartiness. Knife work should respect fiber direction, and cooking methods must account for water content and cell integrity. Substitutions require caution, as structural analogs like fennel or rhubarb behave differently under heat and pressure.

Ultimately, mastering the use of celery begins with seeing it not as a passive ingredient, but as a dynamic, living system—one whose design has been refined by nature and agriculture to deliver both sustenance and sensory pleasure. Whether you're building a sauce, crafting a salad, or simmering a stock, a deeper understanding of celery’s structure leads to smarter, more effective cooking.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?