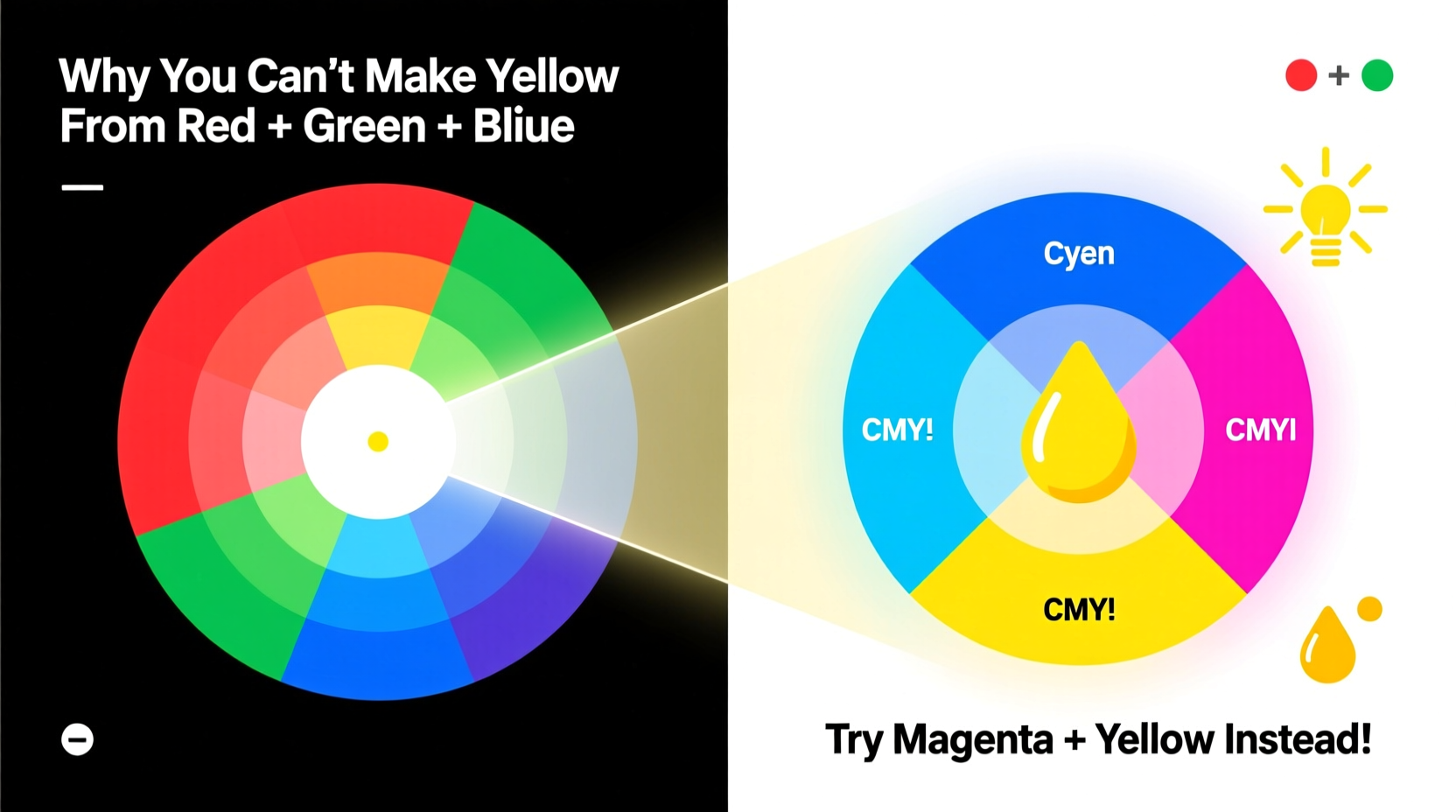

Color mixing is foundational in art, design, photography, and digital media—but it’s also one of the most misunderstood topics. Many people assume that combining red, green, and blue (RGB) will produce yellow because they’ve seen RGB used in screens. The reality, however, is more nuanced. You cannot create yellow by physically mixing red, green, and blue pigments. In fact, doing so typically results in a dull brown or muddy gray. To understand why—and how to actually produce vibrant yellow—you need to distinguish between additive and subtractive color systems.

The Science Behind Color Mixing Systems

There are two primary models of color mixing: additive and subtractive. They operate under fundamentally different principles, and confusing them leads to common misconceptions—especially about yellow.

Additive color mixing applies to light. When red, green, and blue lights overlap, they combine to form white. This system powers your smartphone, computer monitor, and television. In this context, yellow is created by combining red and green light—no blue required. That’s why on-screen yellow appears bright and luminous; it's literally glowing light.

Subtractive color mixing, on the other hand, applies to physical materials like paint, ink, or dye. These substances absorb (subtract) certain wavelengths of light and reflect others. When you mix paints, each added pigment absorbs more light, resulting in darker tones. In this model, combining red, green, and blue pigments doesn’t yield yellow—it yields a dark, desaturated mess.

“People often confuse how screens generate color with how pigments work. Yellow on a screen isn’t painted—it’s lit.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Color Scientist at MIT Media Lab

Why Red + Green + Blue Paint Doesn’t Make Yellow

When artists attempt to mix red, green, and blue paint expecting yellow, they’re applying logic from digital displays to physical media—a critical error. Pigments don’t emit light; they reflect it selectively. Each pigment removes specific wavelengths from ambient light. The more pigments you add, the more light gets absorbed.

Red paint absorbs cyan light (a mix of green and blue), reflecting red. Green paint absorbs magenta (red and blue), reflecting green. Blue absorbs yellow (red and green), reflecting blue. When all three are mixed, their combined absorption covers nearly the entire visible spectrum, leaving little to reflect. The result? A near-black or murky brown.

This explains why mixing all three primary colors in painting usually produces a neutral tone suitable for shading—not a vibrant secondary color like yellow.

What Actually Works: How to Create True Yellow

To produce clean, vivid yellow in physical media, start with the correct primaries: cyan, magenta, and yellow (CMY)—the foundation of printing and professional color theory.

In the CMY system:

- Cyan + Magenta = Blue

- Magenta + Yellow = Red

- Yellow + Cyan = Green

But where does yellow come from? It’s not made by mixing—it’s used as a base. Pure yellow pigment reflects red and green light while absorbing blue. That’s why yellow is a primary in subtractive mixing: it cannot be created by blending other pigments without loss of saturation.

If you're working with traditional artist paints labeled as \"red, yellow, blue\" (RYB), recognize that this is a simplified educational model. Modern understanding favors CMY for accuracy. Even within RYB, yellow is still a starting point, not an outcome.

Alternative Ways to Achieve Bright Yellow Tones

While you can't mix yellow from scratch, you can enhance or modify it effectively:

- Use high-quality cadmium or arylide yellow pigments – These offer superior opacity and brightness.

- Lighten with white, never with other hues – Adding red or green will shift the tone toward orange or olive.

- Adjust temperature with minimal touches – A hint of red warms yellow into golden tones; a trace of blue cools it toward chartreuse (though too much turns it green).

| Mixing Goal | Recommended Method | Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Bright Yellow | Use pure yellow pigment | Mixing from red/green/blue |

| Golden Yellow | Yellow + tiny amount of red | Adding brown or black |

| Lemon Yellow | Yellow + white or touch of green | Using blue or excess white |

| Olive Green | Yellow + blue | Adding red or black prematurely |

Mini Case Study: A Painter’s Mistake and Recovery

Sophie, a beginner watercolorist, wanted to create a sunflower painting. She didn’t have yellow paint and thought she could mix it from her red, green, and blue tubes. After several attempts, she ended up with a series of muddy, lifeless centers. Frustrated, she consulted a local art instructor.

The instructor explained the difference between light-based and pigment-based color. She showed Sophie how to purchase a dedicated yellow pigment and demonstrated proper mixing techniques. Within minutes, Sophie achieved radiant petals using lemon yellow and cadmium yellow. Her next piece glowed with authenticity—all because she stopped trying to recreate yellow and started using it as a foundation.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Mix Colors Without Losing Saturation

Follow this practical sequence to maintain vibrancy and avoid muddiness:

- Start with clean brushes and palette – Residue from previous mixes contaminates new blends.

- Select accurate primary pigments – Use cyan (not turquoise), magenta (not pink), and true yellow.

- Mix only two primaries at a time – Three-way mixes quickly become dull.

- Test on scrap paper first – Especially important when adjusting ratios.

- Label your custom mixes – Helps replicate successful combinations later.

- Clean tools immediately after use – Prevents dried paint from affecting future projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I make yellow if I mix red and green paint?

No. While red and green *light* combine to make yellow in digital displays, red and green *pigments* create a brownish or olive tone due to overlapping light absorption. The result lacks the luminosity of true yellow.

Why do TVs use red, green, and blue to make yellow?

Screens use additive color mixing, where colored lights emit rather than reflect. Red and green light together stimulate both red and green receptors in your eyes, which your brain interprets as yellow. No physical blending occurs—just overlapping beams of light.

Is yellow really a primary color?

Yes—in subtractive color systems like printing and painting, yellow is a primary because it cannot be created by mixing other pigments without significant loss of quality. While some educational models teach red, yellow, blue as primaries, modern color science recognizes cyan, magenta, and yellow as more accurate.

Checklist: Smart Practices for Effective Color Mixing

- ☑ Understand whether you're working with light (additive) or pigment (subtractive)

- ☑ Keep yellow as a starting point, not a target

- ☑ Invest in high-saturation yellow pigments

- ☑ Limit mixes to two colors unless intentionally graying a tone

- ☑ Avoid using black to darken yellows—use complementary violet instead

- ☑ Store paints properly to prevent oxidation and fading

Conclusion: Embrace the Right Tools for the Job

Trying to make yellow from red, green, and blue pigments is like trying to bake bread without flour—it might seem logical at first, but the fundamentals don’t support it. The key to mastering color isn’t memorizing formulas, but understanding systems. Once you grasp that yellow belongs to the starting lineup—not the final blend—you unlock greater control over your palette.

Whether you're designing, painting, or teaching, let go of outdated assumptions. Choose the right primaries, respect the physics of light and pigment, and work with—not against—the nature of color. Your artwork will gain clarity, brilliance, and authenticity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?