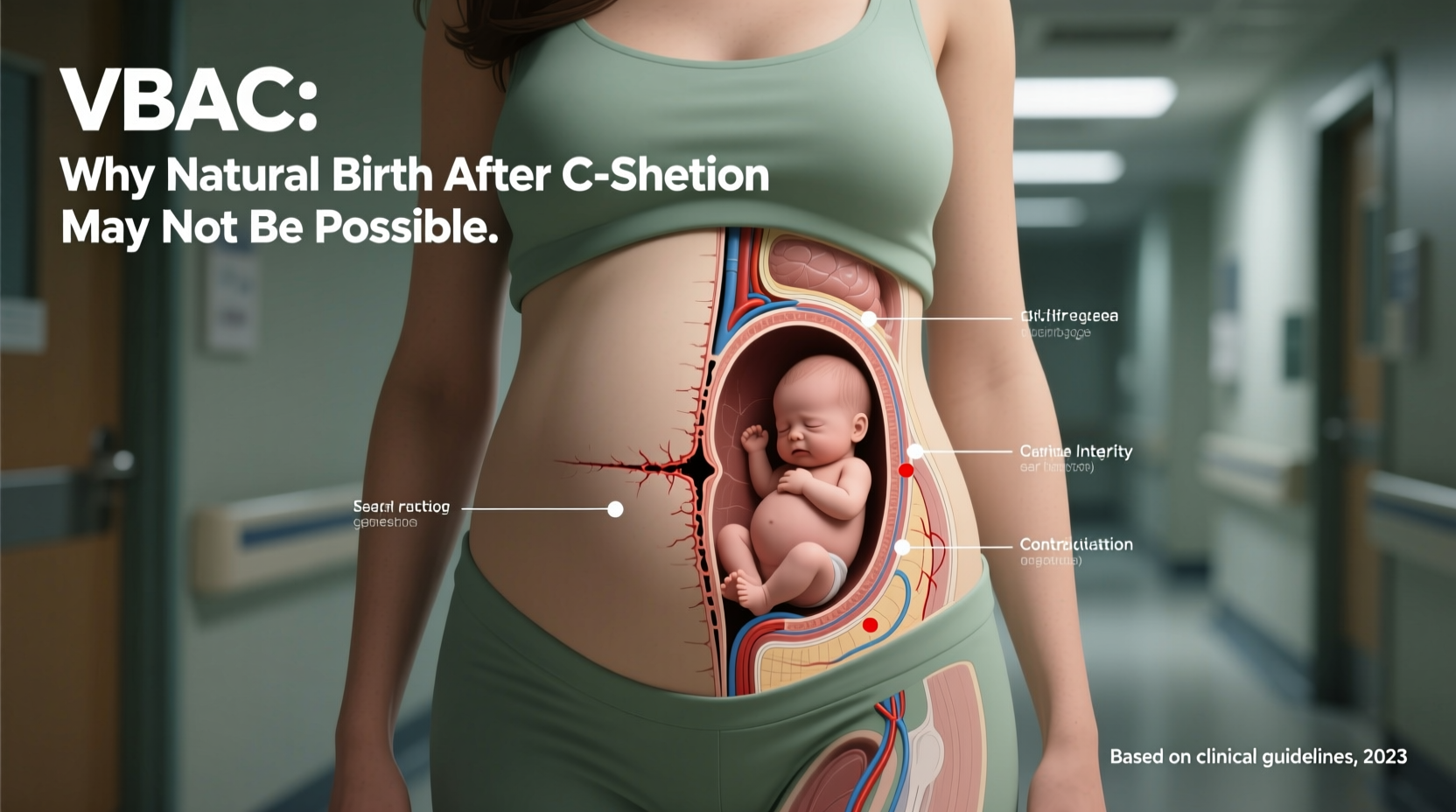

For many women who have delivered via cesarean section, the desire to experience a vaginal birth in a subsequent pregnancy—known as a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC)—is both emotionally and physically compelling. The benefits of avoiding another major surgery, faster recovery times, and a more natural birthing process are strong motivators. However, despite growing support for VBAC in certain cases, it is not always a safe or viable option. Medical history, uterine anatomy, institutional policies, and individual health conditions can all contribute to making a VBAC impossible or too risky to attempt.

This article explores the key reasons why a VBAC may not be possible, offering clarity on clinical guidelines, anatomical limitations, and real-world considerations that influence birth planning after a C-section.

Understanding VBAC: What It Is and Why It Matters

VBAC refers to the delivery of a baby vaginally after a previous cesarean birth. In the past, the standard medical advice was “once a cesarean, always a cesarean.” Today, research supports VBAC as a safe and reasonable option for many women, with success rates between 60% and 80% in carefully selected candidates.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorses VBAC as a safe choice for most women with one prior low-transverse cesarean incision. Yet, even with this endorsement, not every woman qualifies. Understanding the barriers—both medical and logistical—is essential for informed decision-making.

Medical and Anatomical Reasons a VBAC May Not Be Possible

Certain physical and medical factors make attempting a VBAC unsafe. These are often non-negotiable from a clinical standpoint due to the risk of uterine rupture—a rare but life-threatening complication.

1. Type of Previous C-Section Incision

The location and type of uterine incision from a prior cesarean play a decisive role. A low transverse incision—made horizontally across the lower part of the uterus—is associated with the lowest risk of rupture during labor. This makes VBAC a potential option.

In contrast, a classical (vertical) incision, typically made in the upper segment of the uterus, significantly increases the risk of uterine rupture during labor contractions. Women with this type of scar are generally advised against VBAC and directed toward a repeat cesarean.

2. Multiple Prior Cesareans

While some women with two previous C-sections may still be eligible for VBAC under strict protocols, most healthcare providers and hospitals do not support trial of labor after multiple cesareans (TOLAC). Each additional cesarean increases the risk of placental complications (like placenta accreta) and uterine weakness, making VBAC less safe.

3. Uterine Rupture History

If a woman has previously experienced a uterine rupture—whether during a VBAC attempt or in a prior pregnancy—the risk of recurrence is too high. Repeat vaginal delivery is contraindicated in such cases.

4. Other Uterine Surgeries

Women who have had other major uterine procedures, such as a myomectomy (fibroid removal) that entered the uterine cavity, may have compromised uterine integrity. These scars can weaken the wall and increase rupture risk, ruling out VBAC.

Hospital Policies and Access to Care

Even if a woman is medically eligible for VBAC, access to care can be a significant barrier. Not all hospitals or birthing centers support VBAC attempts due to staffing, facility, or liability concerns.

ACOG recommends that VBAC should only be attempted in facilities equipped to perform an emergency cesarean within 30 minutes. Many community hospitals lack 24/7 anesthesia or surgical teams, which disqualifies them from offering VBAC programs.

As a result, some women must travel long distances to find a hospital that supports VBAC—even if their doctor is supportive. In rural areas, this lack of access effectively eliminates the option regardless of personal preference or medical suitability.

“VBAC is a patient-centered option, but it requires institutional readiness. Without immediate surgical backup, we cannot offer it safely.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Maternal-Fetal Medicine Specialist

Personal and Pregnancy-Related Risk Factors

Beyond surgical history and hospital policy, current pregnancy conditions and maternal health also influence VBAC eligibility.

1. Fetal Position and Size

A baby in a breech (feet-first) or transverse (sideways) position cannot be delivered vaginally in most cases. Additionally, suspected fetal macrosomia (a very large baby, especially over 4,500 grams or 9 lbs 15 oz in diabetic mothers) increases the risk of shoulder dystocia and failed labor progression, leading providers to discourage VBAC.

2. Placental Complications

Conditions like placenta previa (where the placenta covers the cervix) or placenta accreta (abnormal attachment to the uterine wall) make vaginal delivery dangerous or impossible. These risks are heightened in women with prior cesareans, particularly multiple ones.

3. Maternal Health Conditions

Chronic conditions such as severe heart disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or a history of stroke may limit safe labor options. In these cases, minimizing labor stress through planned cesarean may be the safest route.

4. Short Interpregnancy Interval

Getting pregnant less than 18 months after a C-section doesn’t allow the uterine scar adequate time to heal. Studies show this increases the risk of uterine rupture during labor, reducing VBAC safety.

| Risk Factor | Impact on VBAC Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Classical C-section incision | Not eligible – high rupture risk |

| Two or more prior C-sections | Likely not eligible – varies by provider/hospital |

| Placenta previa | Not eligible – blocks vaginal delivery |

| Breech fetal position | Not eligible without version attempt |

| Interpregnancy interval < 18 months | May be discouraged due to healing concerns |

Real-World Example: When VBAC Isn’t an Option

Samantha, 34, had her first child via emergency cesarean at 38 weeks due to fetal distress. She strongly desired a VBAC with her second pregnancy and researched extensively. Her OB-GYN reviewed her records and confirmed she had a low-transverse incision—good news for VBAC eligibility.

However, at 34 weeks, an ultrasound revealed her baby was in a frank breech position. External cephalic version (ECV) was attempted but unsuccessful. Given the persistent breech presentation and hospital policy against VBAC in non-head-down positions, Samantha was advised to schedule a repeat cesarean. Despite her disappointment, she understood the risks and prioritized safety for both herself and her baby.

Her case illustrates how even favorable surgical history can be overridden by current pregnancy dynamics.

Step-by-Step: Evaluating Your VBAC Eligibility

If you're considering VBAC, follow this sequence to assess feasibility:

- Obtain your surgical records – Confirm the type of uterine incision from your prior C-section.

- Consult a VBAC-supportive provider – Choose an OB-GYN or midwife experienced in managing VBAC births.

- Review current pregnancy factors – Discuss fetal position, estimated size, placental location, and your overall health.

- Check hospital capabilities – Ensure your chosen facility allows VBAC and has emergency resources available.

- Develop a flexible birth plan – Prepare for the possibility of a repeat cesarean, even if VBAC is your goal.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I try VBAC after two C-sections?

It depends. Some providers and institutions permit VBAC after two low-transverse cesareans if there are no other complicating factors. However, most recommend elective repeat cesarean due to increased risks. Always consult a maternal-fetal medicine specialist for personalized advice.

What happens if I go into labor unexpectedly and am not eligible for VBAC?

If you’re not a candidate for VBAC and go into spontaneous labor, your care team will closely monitor you. If labor progresses normally and there are no signs of distress or rupture, some providers may allow a cautious trial of labor. However, if risks emerge—or if your history absolutely contraindicates VBAC—you will likely undergo an urgent cesarean.

Does insurance cover VBAC?

Most insurance plans cover VBAC since it’s recognized as a medically valid option. However, if you choose a birth center or provider that doesn’t accept your insurance, out-of-pocket costs may apply. Verify coverage with your provider and insurer early in pregnancy.

Conclusion: Making an Informed Decision

While VBAC offers a meaningful path to natural birth after a cesarean, it is not universally possible. Medical history, fetal conditions, and healthcare infrastructure all shape what options are safe and available. The goal is not to achieve a specific type of birth, but to ensure the health and safety of both mother and baby.

By understanding the reasons why VBAC may not be feasible, you empower yourself to engage in honest conversations with your care provider, advocate for appropriate care, and prepare emotionally and practically for your birth experience—whatever form it takes.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?