Taro root is a staple tuber in tropical and subtropical cuisines around the world, prized for its earthy sweetness, creamy texture when cooked, and remarkable versatility. While often compared to the common potato due to its starchy nature and culinary applications, taro is botanically distinct, nutritionally unique, and offers a more complex flavor profile. Understanding the differences between taro root and potato is essential for home cooks looking to expand their ingredient knowledge, improve dietary diversity, or authentically prepare dishes from Polynesian, Caribbean, West African, or Southeast Asian traditions. This guide provides a detailed comparison of taro and potato, covering their origins, physical traits, taste, nutritional benefits, cooking methods, and practical kitchen uses.

Definition & Overview

Taro root (Colocasia esculenta) is an edible corm—a swollen underground stem—that has been cultivated for over 7,000 years, primarily in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, Africa, and parts of South America. It belongs to the Araceae family, which includes ornamental plants like elephant ears, though only the corms and young leaves (when properly prepared) are safe for consumption. Raw taro contains calcium oxalate crystals, which can cause irritation if ingested, so it must always be cooked before eating.

In contrast, the potato (Solanum tuberosum) is a true tuber—developing from modified roots—and originated in the Andes Mountains of South America. Domesticated over 7,000–10,000 years ago, it became a global staple after European exploration. Unlike taro, most potatoes are safe to eat once cooked, though green-skinned or sprouted specimens may contain solanine, a toxic alkaloid.

Both are energy-dense starch sources, but taro stands out for its higher fiber content, lower glycemic index, and richer mineral profile. It plays a central role in traditional dishes such as Hawaiian poi, Filipino *nilagang gabi*, Jamaican *dasheen*, and Chinese taro dumplings. Potatoes dominate Western cuisine through fries, mashed preparations, roasting, and boiling.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Taro Root | Potato |

|---|---|---|

| Botanical Type | Corm (swollen stem) | Tuber (modified root) |

| Flavor Profile | Earthy, nutty, mildly sweet with a hint of vanilla | Neutral, starchy, slightly sweet or buttery depending on variety |

| Texture (Cooked) | Dense, creamy, slightly fibrous; becomes sticky when mashed | Soft, fluffy (russet), waxy (red/yellow), or creamy (Yukon Gold) |

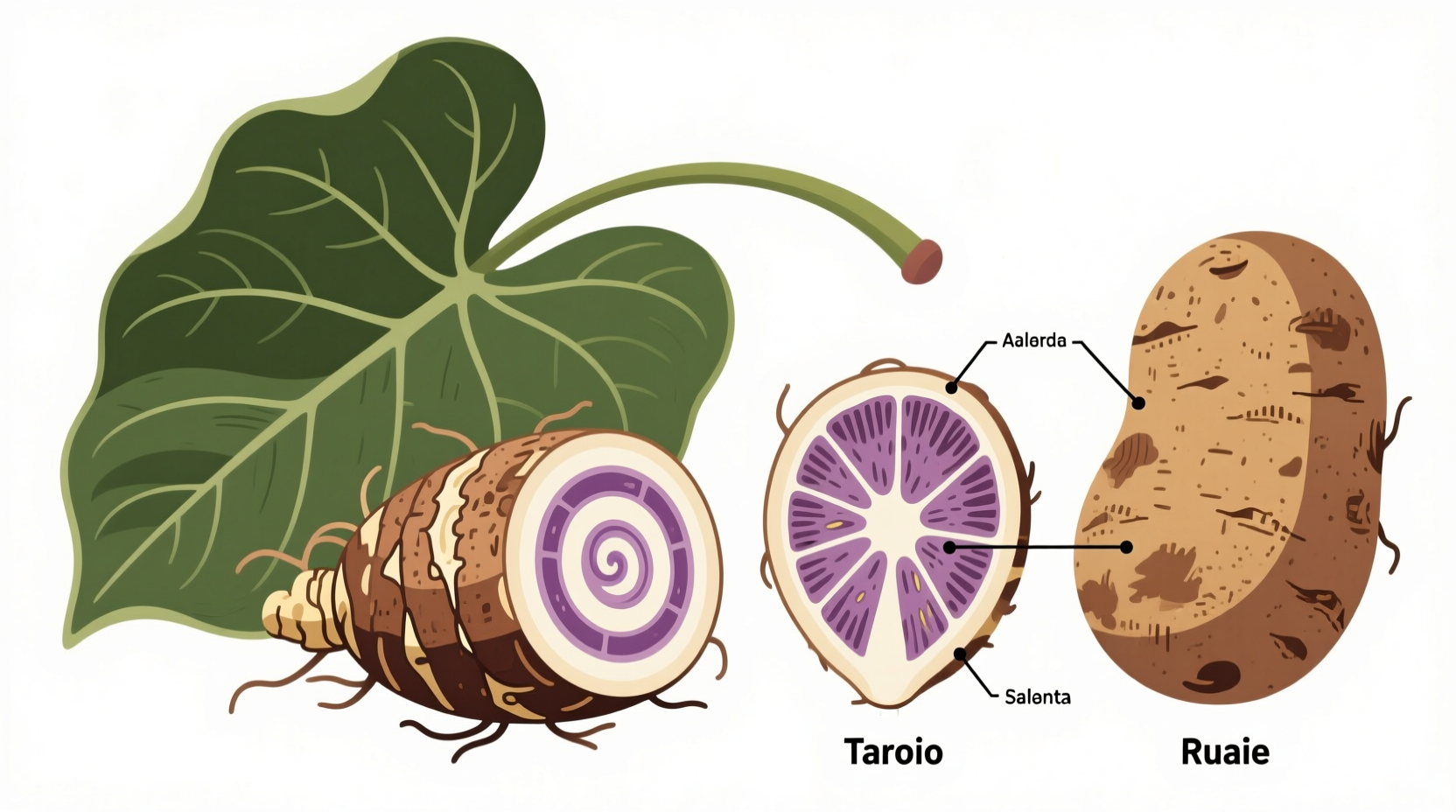

| Color (Flesh) | White to pale lavender with small purple specks; some varieties deep purple | White, yellow, or occasionally purple-red |

| Peel Appearance | Brown, hairy skin resembling coconut fiber; tough and fibrous | Thin brown, red, or golden skin; smoother texture |

| Shelf Life (Uncooked) | 1–2 weeks at cool room temperature; sensitive to cold and moisture | 2–4 weeks in a cool, dark, dry place |

| Toxicity (Raw) | Contains calcium oxalate raphides—must be cooked thoroughly | Contains solanine in green/sprouted areas—should be avoided raw |

Practical Usage: How to Use Taro Root in Cooking

Taro root requires careful handling due to its irritating compounds. Always wear gloves when peeling raw taro to avoid skin itching or dermatitis caused by calcium oxalate. Once peeled, immediately submerge in cold water to prevent oxidation and reduce residue.

Cooking neutralizes taro’s irritants and enhances its natural sweetness. Common preparation methods include:

- Boiling: Peel and cut into chunks, then boil for 20–30 minutes until fork-tender. Ideal for mashing into poi or adding to soups and stews.

- Steaming: Preserves more nutrients than boiling. Use steamed taro in dim sum fillings or as a side dish.

- Frying: Sliced thinly and deep-fried, taro makes crisp chips or puffs up into lacy \"taro nests\" used in Asian plating.

- Baking/Roasting: Roast cubed taro with oil and spices for a hearty side. It caramelizes slightly, enhancing its nutty notes.

- Grinding: Cooked taro can be pureed and used as a thickener or base for desserts like taro bubble tea, mochi, or puddings.

Tip: To minimize mess and stickiness when working with cooked taro, lightly oil your knife and cutting board. For smooth mash, pass it through a food mill rather than using a blender, which can make it gluey.

In professional kitchens, taro is valued for its ability to mimic other ingredients while contributing visual appeal—especially purple-fleshed varieties that lend a naturally vibrant hue to pastries, buns, and ice creams without artificial coloring.

Variants & Types of Taro Root

Over 200 varieties of taro exist globally, differing in size, color, texture, and regional adaptation. The most commonly available types include:

- Dasheen: Large corms with white flesh and purple speckles; firm texture ideal for boiling, mashing, or frying. Predominant in Caribbean and West African cooking.

- Eddoe (or Chin-chin): Smaller, elongated corms with pinkish tips and drier flesh. Often used in stir-fries and braises, especially in Chinese and Japanese cuisine.

- Colocasia esculenta var. aquatilis: Grown in flooded fields (like rice paddies); yields tender, high-moisture corms preferred for poi in Hawaii.

- Purple Taro (e.g., Okinawan Sweet Taro): Bright lavender flesh with a sweeter, milder flavor. Popular in modern fusion desserts and health-conscious recipes.

Each type responds differently to heat. Dasheen holds shape well during long cooking, making it suitable for curries. Eddoe absorbs flavors readily, ideal for seasoned dishes. Purple taro breaks down easily when boiled, perfect for smooth purees.

Potatoes also come in numerous cultivars, broadly categorized by texture:

- Starchy (e.g., Russet): High in amylose, best for baking, frying, and mashing.

- Waxy (e.g., Red Bliss, Fingerling): High moisture, low starch; retain shape in salads and soups.

- All-Purpose (e.g., Yukon Gold): Balanced starch and moisture; versatile across techniques.

While both offer variety, taro’s diversity is less standardized in Western markets, where dasheen and purple taro dominate supermarket offerings.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients: Taro vs. Potato

Despite superficial similarities, taro and potato differ significantly in structure, performance, and nutrition. Here's a focused breakdown:

| Aspect | Taro Root | Potato |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Density (per 100g, boiled) | Higher in dietary fiber (6g vs. 2.2g), vitamin E, magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc | Higher in vitamin C and potassium; moderate B6 |

| Glycemic Index (GI) | ~50 (low to medium)—slower glucose release | ~78 (high)—rapid blood sugar spike, especially russets |

| Calories | 112 kcal | 87 kcal |

| Carbohydrates | 26.5g | 20g |

| Protein | 1.5g | 2g |

| Gluten-Free Status | Yes | Yes |

| Cooking Behavior | Becomes sticky when mashed; absorbs flavors moderately | Can be fluffy or waxy; excellent binder in croquettes or pancakes |

| Common Substitutions | Can replace potato in soups, gratins, or fries—but alters texture and flavor | Potato not ideal substitute for taro in desserts or poi due to lack of viscosity and color |

\"Taro brings a depth you don’t get with potatoes—it’s earthier, almost mushroom-like, and adds a luxurious silkiness to sauces and purees.\" — Chef Mei Ling, Honolulu-based Pacific Rim cuisine specialist

Practical Tips & FAQs

Can I eat taro raw?

No. Raw taro contains needle-like calcium oxalate crystals that can cause intense mouth and throat irritation, swelling, and discomfort. Always cook taro thoroughly—boiling, steaming, or baking—for at least 20 minutes until soft.

How do I store taro root?

Keep unpeeled taro in a cool, dry, well-ventilated place away from direct sunlight. Do not refrigerate, as cold temperatures can damage the cellular structure and lead to spoilage. Use within 10–14 days. Once peeled or cooked, store in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 5 days.

Is taro healthier than potato?

In several key areas, yes. Taro has nearly three times the fiber of white potatoes, a lower glycemic index, and higher levels of magnesium and vitamin E. However, potatoes provide more vitamin C and are lower in calories. For blood sugar management and digestive health, taro is generally superior. For quick energy or lighter meals, potatoes may be preferable.

Can I substitute taro for potato in recipes?

You can, but with adjustments. Taro absorbs more oil when fried and becomes gumminess when over-blended. In mashed form, mix with cream or coconut milk to balance texture. For roasting, increase oil slightly due to taro’s denser nature. Avoid substituting in dishes requiring fluffiness (e.g., classic mashed potatoes).

Why does my mouth itch after eating taro?

This likely means the taro was undercooked. Even slight crunch indicates residual calcium oxalate. Ensure taro is fully tender before serving. Peeling thoroughly and discarding any fibrous core sections also helps.

Are taro leaves edible?

Yes, but only when cooked. Taro leaves (known as *callaloo* in the Caribbean or *palai bhaji* in India) are rich in vitamins A and C, iron, and protein. They must be boiled for at least 10–15 minutes to destroy toxins. Use in soups, stews, or wrapped around fillings (like in lau lau).

What are common dishes featuring taro?

- Poi (Hawaii): Fermented mashed taro, served as a staple side.

- Taro Balls (China/Taiwan): Chewy spheres filled with sweet or savory centers, often in hot pots or desserts.

- Taro Bubble Tea: Powdered or pureed taro blended into milk tea, known for its purple hue and mild sweetness.

- Callaloo (Trinidad & Tobago): Stewed taro leaves with coconut milk, okra, and peppers.

- Taro Chips: Thinly sliced and fried until crisp, seasoned with salt or spices.

Storage Tip: If storing cut taro, keep it submerged in water with a splash of lemon juice to prevent browning. Change water daily.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Taro root and potato, while both starchy staples, belong to different plant families, possess distinct textures and flavors, and serve unique roles in global cuisines. Taro offers a nuttier, earthier taste, denser consistency, and superior fiber content, making it ideal for slow-cooked dishes, thickening agents, and visually striking desserts. Its requirement for thorough cooking sets it apart from the more forgiving potato, which excels in quick, high-heat applications and fluffy preparations.

The decision to use taro instead of potato should consider nutritional goals, desired texture, and cultural authenticity. For those managing blood sugar, increasing fiber intake, or exploring international flavors, taro is a valuable addition to the pantry. Meanwhile, potatoes remain unmatched in accessibility, versatility, and familiarity across everyday Western meals.

Understanding these differences empowers cooks to make informed choices, experiment confidently, and appreciate the rich agricultural heritage behind each humble tuber.

Ready to try taro? Start with pre-cooked frozen taro cubes or canned versions to simplify preparation. Incorporate into soups or mash with butter and coconut milk for a gentle introduction to its unique character.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?