Clouds drifting just above the treetops or shrouding mountain ridges can create dramatic, almost surreal scenes. But what causes clouds to appear so unusually low? While it might seem like a simple shift in altitude, the reasons behind low cloud formations are deeply rooted in atmospheric physics, moisture levels, temperature gradients, and geographic influences. Understanding why clouds hang low isn’t just fascinating—it’s essential for pilots, hikers, meteorologists, and anyone who spends time observing the sky.

The Science Behind Cloud Formation and Altitude

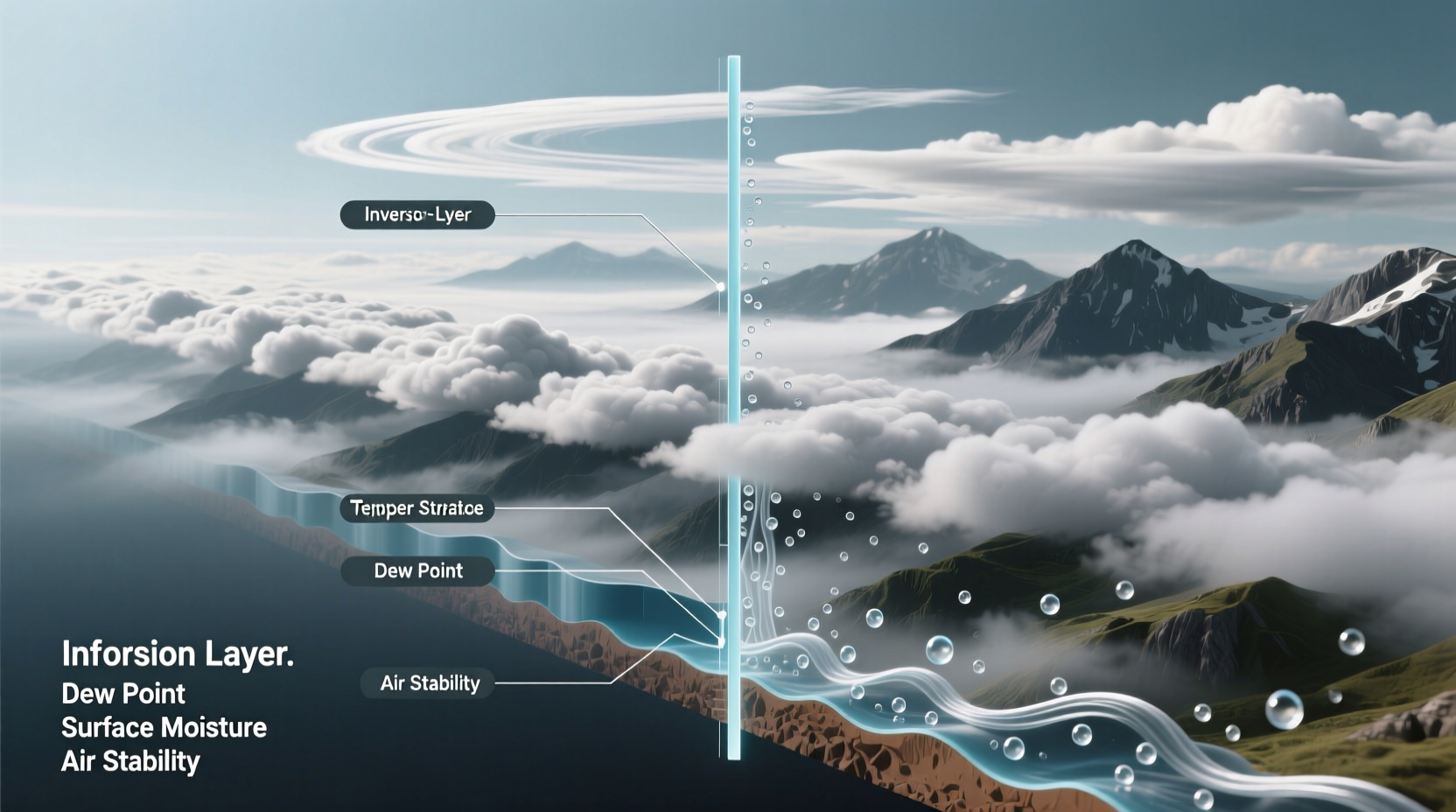

Clouds form when warm, moist air rises and cools to its dew point—the temperature at which water vapor condenses into tiny droplets around microscopic particles in the atmosphere. The altitude at which this happens determines how high or low a cloud appears. Several key variables govern this process: humidity, temperature lapse rate, air pressure, and lifting mechanisms such as frontal systems or terrain-induced uplift.

In stable atmospheric conditions, air cools predictably with altitude—about 6.5°C per kilometer (the environmental lapse rate). However, when a layer of warm air sits above cooler surface air (a temperature inversion), vertical mixing is suppressed. This traps moisture near the ground, leading to fog or stratus clouds that hover just above the surface.

Key Factors That Lower Cloud Base Height

Several interrelated factors contribute to clouds forming closer to the Earth’s surface. These include humidity levels, surface temperature, wind patterns, and topography.

- High Humidity: When relative humidity near the surface approaches 100%, even slight cooling can trigger condensation at low altitudes.

- Cool Surface Temperatures: Cold ground or water surfaces cool the air above them, reducing its capacity to hold moisture and promoting low cloud development.

- Temperature Inversions: Normally, air gets colder with height. During an inversion, warmer air aloft caps cooler, moist air below, preventing dispersion and encouraging persistent low clouds.

- Maritime Influence: Coastal regions frequently experience advection fog and low stratus as warm air moves over cold ocean currents, cooling from below.

- Orographic Lift: Mountains force air upward, cooling it rapidly. If sufficient moisture exists, clouds form on windward slopes, sometimes descending into valleys.

“Low clouds aren’t anomalies—they’re direct responses to local energy and moisture balances.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Atmospheric Scientist, NOAA

Types of Low Clouds and Their Typical Heights

Not all low clouds are created equal. The World Meteorological Organization classifies clouds based on appearance and altitude. Clouds categorized as “low-level” generally form below 2,000 meters (6,500 feet), but some types regularly appear much lower—sometimes only tens of meters above ground.

| Cloud Type | Average Base Height | Conditions for Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Stratus | 100–2,000 m | Stable air, high humidity, overcast days |

| Fog (surface cloud) | 0–100 m | Radiation cooling, advection over cold surfaces |

| Stratocumulus | 500–2,000 m | Weak convection under inversions |

| Nimbostratus | 500–3,000 m | Warm fronts, steady precipitation |

| Orographic Clouds | Varies by elevation | Moist air forced up slopes |

Among these, fog and stratus are most commonly perceived as “low-hanging.” Fog, technically a ground-level cloud, reduces visibility and creates the illusion of clouds resting on hills or cityscapes.

Real-World Example: San Francisco’s Marine Layer

No discussion of low clouds would be complete without mentioning San Francisco’s iconic summer fog. Each year, millions witness thick banks of low cloud rolling through the Golden Gate Bridge. This phenomenon results from a consistent pattern: hot inland temperatures draw in cool, moist Pacific air. As this marine layer moves ashore, it encounters cooler sea surface temperatures and is capped by a strong temperature inversion several hundred meters up.

The result? A dense stratus deck forming between 300 and 600 meters, often sinking below hilltops and enveloping neighborhoods. Locals know to carry jackets even in July because the cloud base remains stubbornly low during mornings and evenings, only burning off—if at all—by mid-afternoon.

This example illustrates how geography, seasonal heating, and oceanic conditions combine to produce persistently low clouds in one location while neighboring areas remain sunny.

How Weather Systems Influence Cloud Height

Large-scale weather patterns play a decisive role in determining cloud base heights. Two primary systems dominate: warm fronts and high-pressure zones.

During a warm front, warm air glides over a wedge of cooler air near the surface. This gradual ascent leads to widespread, layered clouds that begin high but descend as the front approaches. Pilots often report lowering ceilings—a term for decreasing cloud base height—hours before precipitation begins.

Conversely, high-pressure systems typically bring sinking air, which warms and suppresses cloud formation. Yet under certain conditions—especially in winter—high pressure can lead to prolonged inversions. With no wind to mix the layers, moisture accumulates near the surface, forming shallow stratus or fog that lingers for days.

Step-by-Step: Predicting Low Cloud Events

Understanding when and where low clouds will form allows better planning for outdoor events, aviation, or photography. Follow this sequence to anticipate low-hanging clouds:

- Check surface dew point spread: If air temperature and dew point are within 2–3°C, saturation is likely.

- Look for temperature inversions: Review upper-air soundings or forecast models showing warmer air above cooler surface layers.

- Assess wind direction: Onshore flow in coastal areas increases risk of marine layer development.

- Evaluate terrain: Valleys and basins trap cold air and moisture, especially on clear, calm nights.

- Monitor satellite and radar: Look for smooth, featureless gray areas indicating stratus rather than convective clouds.

Common Misconceptions About Low Clouds

Many assume low clouds indicate stormy weather ahead. While nimbostratus clouds do precede rain, not all low clouds bring precipitation. Stratus may produce drizzle, but more often they simply reduce visibility and sunlight without wetting the ground.

Another myth is that low clouds are always cold. In tropical regions, warm, humid air can generate low cumulus clouds at sea level despite high temperatures. The critical factor isn’t air temperature alone, but the relationship between temperature and moisture content.

FAQ

Can low clouds affect air travel?

Yes. Low cloud ceilings can delay flights, especially at smaller airports without advanced instrument landing systems. Airlines may reroute or hold departures until visibility improves.

Is fog considered a type of cloud?

Absolutely. Fog is defined as a cloud in contact with the ground. It forms through the same physical processes as other clouds but occurs at surface level.

Do low clouds last longer than high ones?

Often, yes. Because they form in stable, moist layers protected from strong winds and solar heating, low clouds like stratus can persist for hours or even days, especially under inversions.

Conclusion: Observing the Sky with New Insight

The next time you see clouds skimming rooftops or wrapping around hills, remember—you’re witnessing precise atmospheric conditions aligning in real time. Low clouds are not random; they are visible indicators of humidity, temperature structure, and airflow dynamics. By learning to read these signs, you gain more than scientific knowledge—you develop a deeper connection with the environment.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?