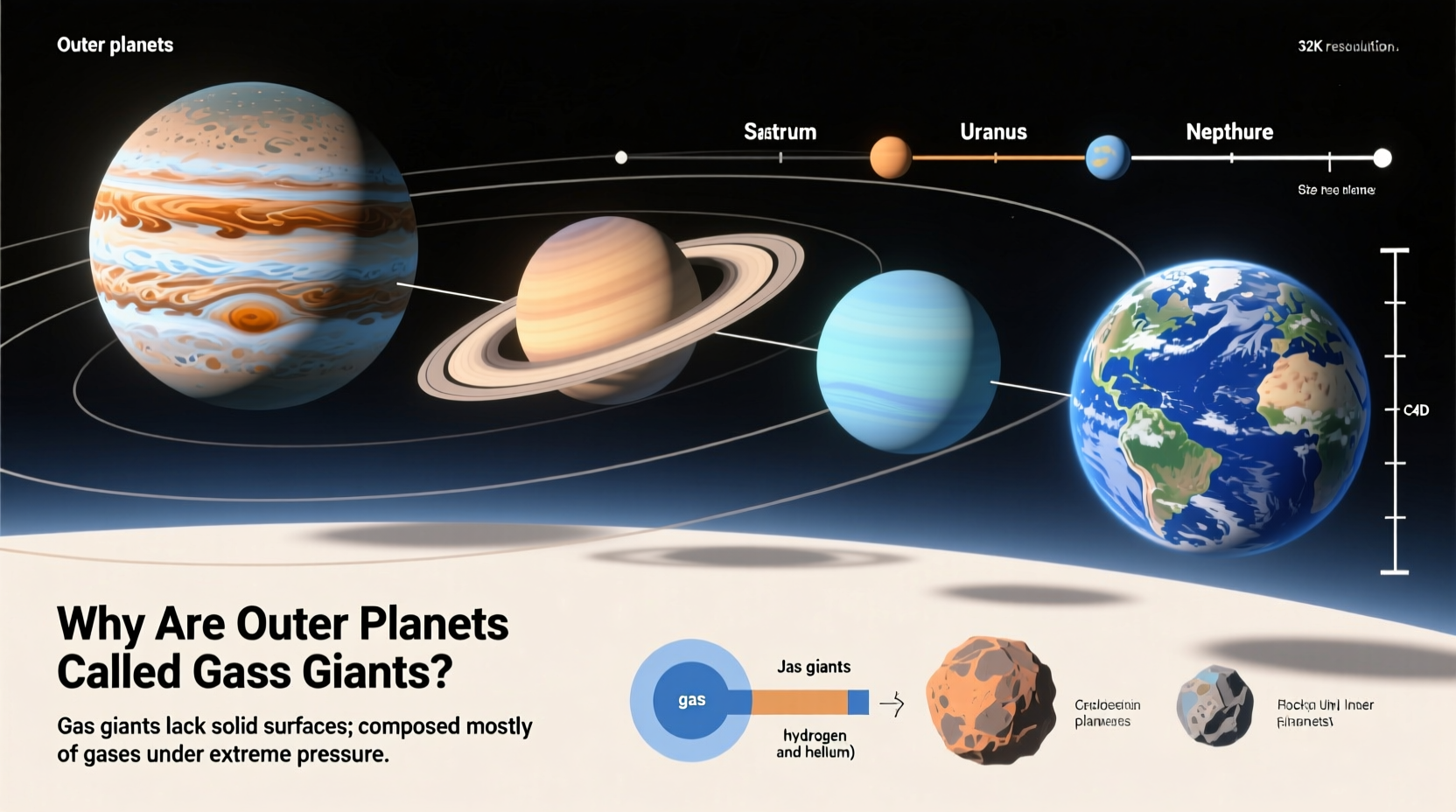

The solar system’s four outer planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—are commonly known as the “gas giants.” But what exactly makes them “giant,” and why are they composed mostly of gas? The term isn’t just poetic; it reflects fundamental differences in planetary structure, formation, and behavior compared to the rocky inner planets like Earth and Mars. Understanding why these distant worlds earned this label reveals not only how our solar system evolved but also how astronomers classify planets beyond our own cosmic neighborhood.

The Origin of the Term \"Gas Giants\"

The phrase “gas giant” was first coined in the mid-20th century as astronomers developed better models of planetary composition. Unlike Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—all primarily made of silicate rock and metal—the outer planets were found to lack solid surfaces and instead consist largely of light elements such as hydrogen and helium. These elements exist in gaseous, liquid, and even metallic states under extreme pressure, but none form a traditional crust or mantle like terrestrial planets.

Jupiter and Saturn are the archetypal gas giants, with over 90% of their mass composed of hydrogen and helium. Uranus and Neptune, while sometimes grouped under the same umbrella, differ significantly in composition and are now more accurately referred to as “ice giants.” Still, all four share the common trait of being massive, low-density bodies dominated by volatile substances rather than rock and metal.

What Makes a Planet a Gas Giant?

To qualify as a gas giant, a planet must meet several key criteria:

- Massive Size: Gas giants dwarf the terrestrial planets. Jupiter alone is over 300 times more massive than Earth.

- Lack of Solid Surface: There's no well-defined surface; instead, the atmosphere gradually thickens into fluid layers under immense pressure.

- Hydrogen and Helium Dominance: These two lightest elements make up most of the planet’s bulk, similar to the Sun’s composition.

- Formation Beyond the Frost Line: They formed in the colder outer regions of the protoplanetary disk, where volatile compounds could condense into ice and attract large amounts of gas.

This formation process allowed gas giants to grow rapidly by accreting gas from the surrounding disk before the young Sun’s radiation blew it away. Their gravitational influence also shaped the architecture of the entire solar system, deflecting comets, capturing moons, and clearing debris from their orbits.

Composition Breakdown: What Are Gas Giants Really Made Of?

Despite the name, gas giants aren't entirely gaseous. As depth increases, so does pressure and temperature, transforming gases into exotic physical states:

- Upper Atmosphere: Visible cloud layers composed of ammonia, ammonium hydrosulfide, and water vapor (in Jupiter and Saturn).

- Metallic Hydrogen Layer: Deep within Jupiter and Saturn, pressures exceed millions of atmospheres, forcing hydrogen into a liquid metallic state capable of conducting electricity—this generates powerful magnetic fields.

- Core Region: Likely a dense mix of rock, metal, and ice, possibly 10–20 times Earth’s mass, though not directly observed.

Uranus and Neptune, while still large, contain higher proportions of “ices” like water, methane, and ammonia—molecules that were frozen in the cold outer solar system. This distinction has led scientists to classify them separately as ice giants, though they’re often included in broader discussions of gas giants due to shared structural traits.

| Planet | Primary Composition | Mass (Earth = 1) | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jupiter | Hydrogen (~75%), Helium (~24%) | 318 | Gas Giant |

| Saturn | Hydrogen (~75%), Helium (~24%) | 95 | Gas Giant |

| Uranus | Water, Methane, Ammonia Ices + H/He envelope | 14 | Ice Giant |

| Neptune | Water, Methane, Ammonia Ices + H/He envelope | 17 | Ice Giant |

“We call them gas giants because they're mostly hydrogen and helium—the same stuff that powers stars—but they never got massive enough to ignite.” — Dr. Linda Essam, Planetary Scientist at Caltech

Why Aren’t All Large Planets Gas Giants?

A common misconception is that any large planet must be a gas giant. However, size alone doesn’t determine classification. For example, super-Earths—exoplanets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune—may be rocky or oceanic without significant gaseous envelopes. The key differentiator is composition and formation history.

In our solar system, the division between inner and outer planets aligns with the “frost line”—a boundary beyond which volatile compounds like water, methane, and ammonia can condense into solid ice grains. Inside this line, only metals and silicates could condense, leading to small, rocky planets. Outside it, icy cores could grow massive enough to gravitationally capture vast amounts of hydrogen and helium from the solar nebula.

This explains why gas giants formed far from the Sun. If they had formed closer, solar radiation would have stripped away their gaseous envelopes before they could accumulate sufficient mass.

Real-World Observation: Voyager and Juno Missions

One of the most compelling validations of the gas giant model came from NASA’s Voyager missions in the late 1970s. As Voyager 1 and 2 flew past Jupiter and Saturn, they revealed turbulent atmospheres, complex storm systems like the Great Red Spot, and extensive moon systems—all sustained by the planets’ enormous gravity and internal heat.

More recently, the Juno spacecraft has provided unprecedented data about Jupiter’s interior. By measuring gravitational fluctuations, Juno helped confirm that Jupiter likely has a diffuse core—partially dissolved and mixed into the surrounding metallic hydrogen layer—challenging earlier assumptions of a compact, solid center.

These missions underscore that gas giants are dynamic, evolving systems. Their deep interiors remain poorly understood, but each new discovery refines our grasp of how such planets function and why they dominate so many planetary systems across the galaxy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are gas giants dangerous to approach?

Yes, extremely. The intense radiation belts around Jupiter, crushing atmospheric pressure, and violent storms make close exploration highly challenging. Spacecraft require heavy shielding and precise trajectories to survive even flybys.

Can you land on a gas giant?

No. There is no solid surface to land on. Any probe descending into a gas giant would eventually be crushed by increasing pressure and heat long before reaching any theoretical core.

Do gas giants have moons?

Yes, and many are among the most fascinating objects in the solar system. Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus may harbor subsurface oceans and conditions suitable for life, making them prime targets for future exploration.

How to Understand Gas Giants: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Start with Solar System Layout: Recognize that the four outer planets are much farther from the Sun than Earth.

- Compare Sizes: Note that Jupiter and Saturn are vastly larger than Earth, both in diameter and mass.

- Examine Composition Data: Look at spectroscopic analyses showing dominant hydrogen and helium signatures.

- Study Atmospheric Features: Observe cloud bands, storms, and auroras driven by internal heat and rapid rotation.

- Review Mission Findings: Explore results from probes like Galileo, Cassini, and Juno for deeper insights into structure and behavior.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Giants of Our Solar System

The term “gas giant” captures something essential about Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—their dominance through sheer scale and their elemental simplicity compared to rocky worlds. Yet these planets are far from simple. They host swirling storms that last centuries, generate powerful magnetic fields, and shepherd dozens of moons in complex orbital dances. They represent a class of planet that is actually more common in the universe than Earth-like worlds.

Understanding why they’re called gas giants opens a window into planetary formation, atmospheric science, and the diversity of worlds beyond our own. As we discover thousands of exoplanets, many of which are gas giants orbiting close to their stars (so-called “hot Jupiters”), the lessons learned from our own solar system become even more valuable.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?