The term \"Caucasian\" is widely used in official forms, medical records, and everyday conversation to describe people of European descent. Yet few pause to consider why individuals from Europe, North Africa, or West Asia are labeled after a region nestled between the Black and Caspian Seas—the Caucasus. The label carries historical weight, scientific flaws, and sociopolitical implications that stretch far beyond geography. Understanding its origins reveals how outdated 18th-century racial theories still influence modern identity categories.

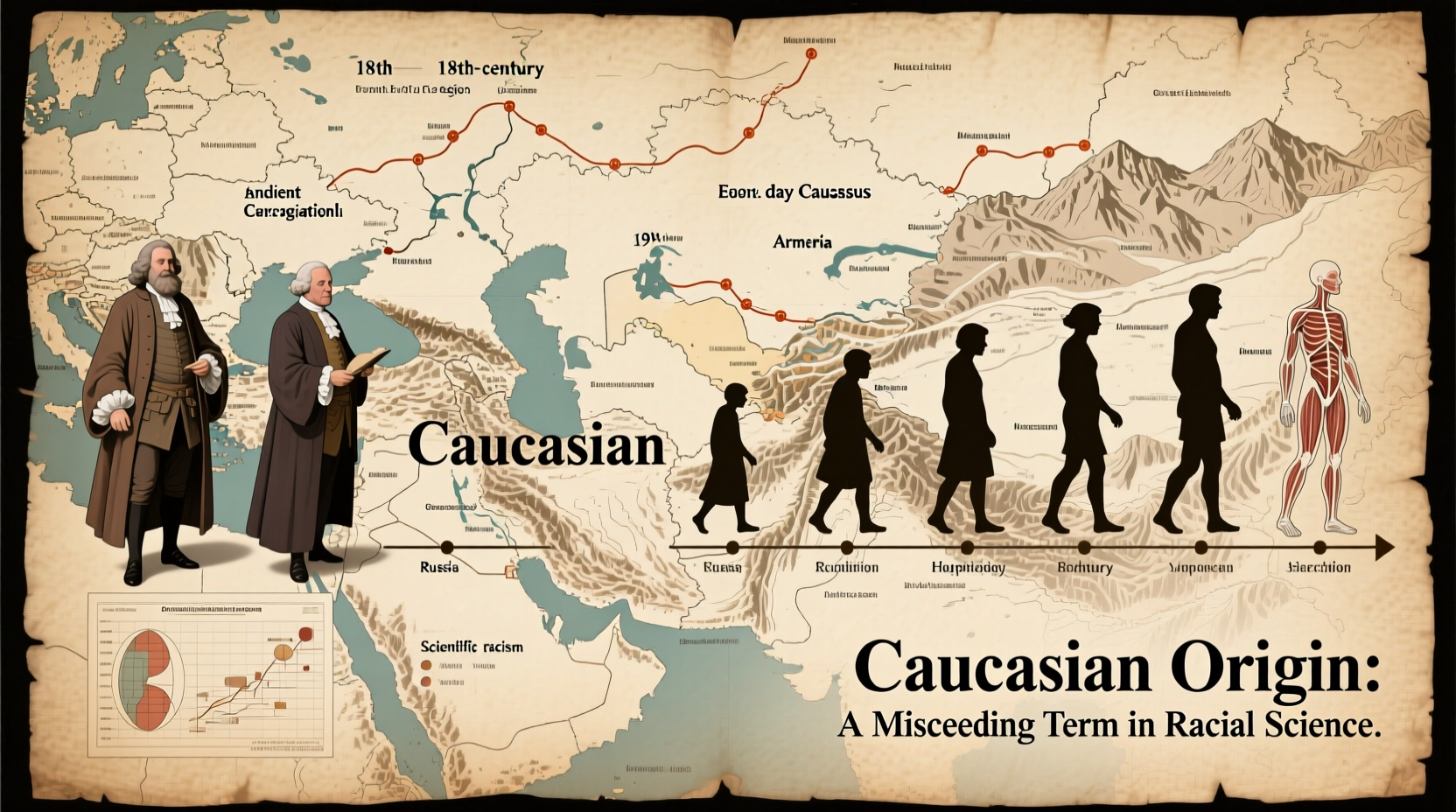

The Birth of a Racial Category

The term \"Caucasian\" as a racial classification originated not from anthropology as we know it today, but from the speculative scholarship of German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the late 1700s. In his 1795 work De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa, Blumenbach proposed five racial divisions: Caucasian, Mongolian, Ethiopian, American, and Malay. He placed the \"Caucasian\" race at the top, associating it with beauty, intelligence, and cultural superiority.

Blumenbach chose the name “Caucasian” not because he believed all white people came from the Caucasus region, but because he based his ideal skull measurements on a single female skull from Georgia—a country in the South Caucasus. He claimed this skull represented the most “primitive” and “beautiful” form of humankind, from which all other races had supposedly degenerated.

“Blumenbach’s choice was arbitrary—he could have picked any skull. But by anchoring whiteness to the Caucasus, he gave pseudoscientific legitimacy to racial hierarchies.” — Dr. Lila Abu-Lughod, Anthropologist, Columbia University

A Misleading Geographical Label

The irony is palpable: the people indigenous to the actual Caucasus region—such as Georgians, Armenians, Chechens, and Azeris—are ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse. Many do not identify as “white” in the American racial context, nor have they historically been grouped with Northern Europeans. Yet the term \"Caucasian\" became shorthand for “white” or “of European descent,” especially in the United States.

This misapplication gained traction through U.S. immigration law and census categorization. In the early 20th century, courts used the term to determine who could be naturalized as citizens under laws restricting non-white immigrants. For example, in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), the Supreme Court ruled that while Thind, an Indian Sikh, might be “Caucasian” in anthropological terms, he was not “white” in the common understanding of the word—thereby denying him citizenship.

Scientific Flaws and Modern Rejection

Modern genetics has dismantled the idea that humanity can be neatly divided into discrete biological races. DNA studies show more genetic variation within so-called racial groups than between them. The concept of a unified “Caucasian” race encompassing everyone from Irish farmers to Iranian scholars lacks genetic coherence.

Despite this, the term persists in medical literature, legal forms, and demographic surveys. Some argue it remains useful for tracking health disparities or social inequities tied to perceived race. However, critics warn that using obsolete classifications risks reinforcing false biological notions of race.

In response, many institutions are shifting toward more precise descriptors such as “European ancestry,” “Middle Eastern,” or “North African,” which reflect geographic and ethnic specificity without invoking discredited racial typologies.

Timeline of the Term’s Evolution

- 1795: Blumenbach introduces “Caucasian” as a racial category based on skull morphology.

- 1800s: The term spreads across Europe and North America, often equated with “white” and linked to ideas of superiority.

- Early 1900s: U.S. courts use “Caucasian” to determine citizenship eligibility, creating legal contradictions.

- Mid-20th Century: UNESCO declares race a social myth; scientists reject hierarchical racial models.

- 21st Century: “Caucasian” remains in bureaucratic use despite growing criticism from scholars and activists.

Why Does This Matter Today?

The continued use of “Caucasian” isn’t just a linguistic quirk—it shapes how we see ourselves and others. In healthcare, for instance, assuming biological similarity among all “Caucasians” can lead to misdiagnosis or inadequate treatment. A Finnish person and a Lebanese person may both be labeled Caucasian, yet their genetic predispositions differ significantly.

Moreover, the term obscures real histories of migration, colonization, and identity. It flattens complex backgrounds into a single, often inaccurate box. As societies become more diverse and data collection more sophisticated, there is increasing pressure to replace vague labels with meaningful, self-identified categories.

Mini Case Study: The Census Conundrum

In 2020, a second-generation Armenian-American woman filled out her U.S. Census form. Under race, she hesitated at the option “White/Caucasian.” While technically eligible, she felt the label erased her ethnic identity and connection to a distinct cultural lineage. She selected “White” but wrote in “Armenian” to assert visibility. Her experience reflects a broader tension: official categories often fail to capture lived identity, forcing people into boxes that don’t fit.

Checklist: Evaluating the Use of 'Caucasian'

- ✅ Ask: Is this term being used for precision or convenience?

- ✅ Consider replacing “Caucasian” with more specific terms like “European,” “Euro-American,” or “Middle Eastern.”

- ✅ Recognize that race is socially constructed, not biologically fixed.

- ✅ In research or policy, prioritize self-identification over imposed categories.

- ✅ Challenge assumptions that link appearance, geography, and genetic destiny.

Do’s and Don’ts of Using Racial Terminology

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Use self-identified labels when possible | Assume all light-skinned people share the same heritage |

| Specify regions (e.g., Southern European, Ashkenazi Jewish) | Use \"Caucasian\" interchangeably with \"white\" without context |

| Educate others on the term’s problematic origins | Treat race as a proxy for genetic uniformity |

| Update institutional language to reflect current science | Perpetuate outdated racial hierarchies through casual usage |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is \"Caucasian\" scientifically accurate?

No. Modern genetics rejects the idea of biologically distinct races. The term “Caucasian” stems from 18th-century craniometry, a pseudoscience that classified humans by skull shape. Today, it has no valid biological basis.

If it's outdated, why is \"Caucasian\" still used?

The term endures due to institutional inertia. It appears in legal documents, medical records, and government forms. While some organizations are phasing it out, change is slow. Social recognition and bureaucratic convenience keep it alive despite scholarly criticism.

Can someone from the Caucasus region be non-Caucasian?

Yes—and this highlights the confusion. People from the Caucasus Mountains speak dozens of languages, practice various religions, and have diverse physical traits. The label “Caucasian” as a race does not accurately represent them. Many prefer national or ethnic identifiers like Georgian, Circassian, or Dagestani.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond Outdated Labels

The term “Caucasian” is a relic of Enlightenment-era attempts to categorize humanity through flawed science and Eurocentric bias. While it persists in everyday language, awareness is growing about its inaccuracies and implications. As society advances toward equity and inclusion, precision in language becomes essential. Replacing vague, historically loaded terms with nuanced, respectful alternatives allows for a more honest understanding of human diversity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?