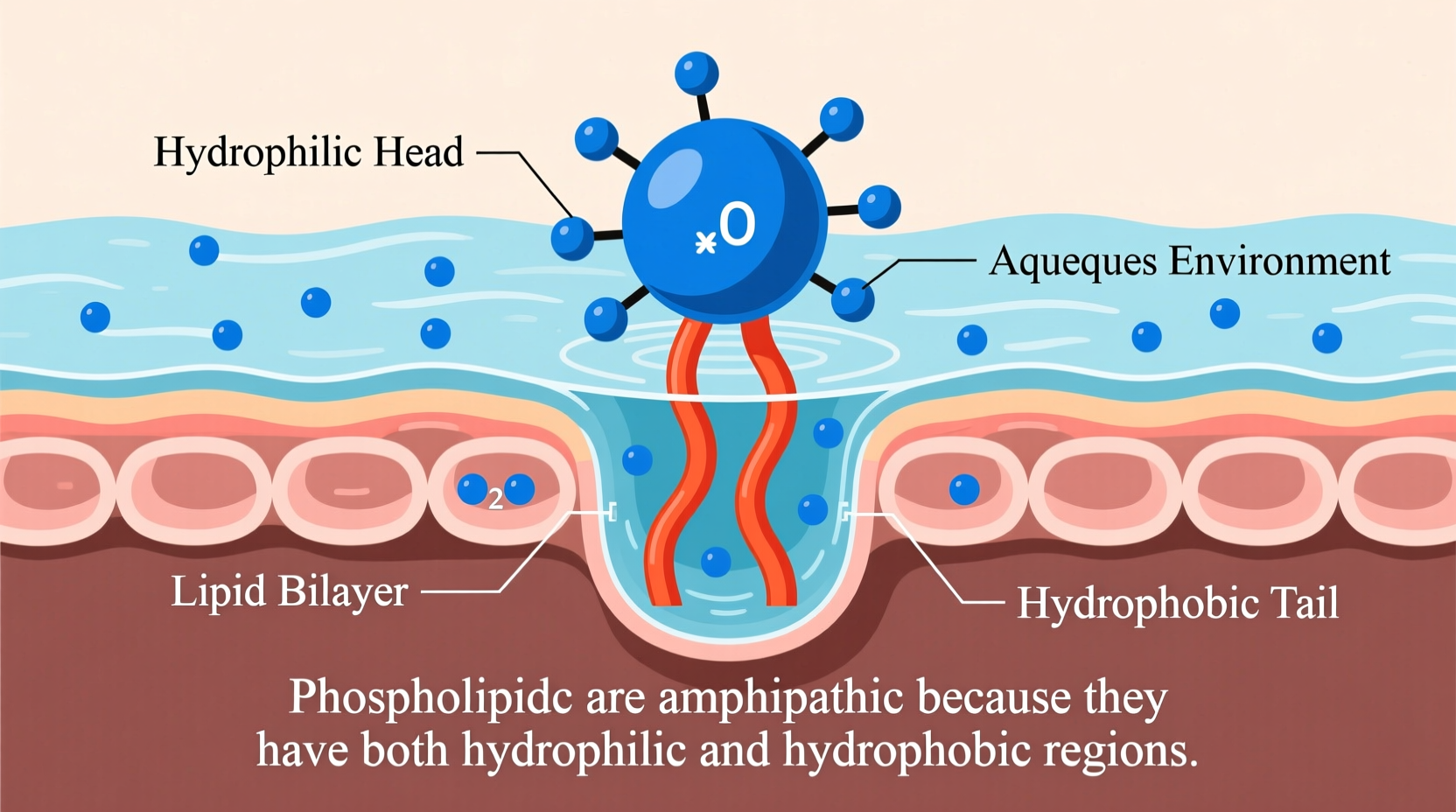

Phospholipids are fundamental building blocks of cellular membranes, playing a crucial role in maintaining the integrity and functionality of cells. One of their most defining characteristics is that they are amphipathic—meaning they possess both hydrophilic (water-loving) and hydrophobic (water-fearing) regions. This dual nature allows them to spontaneously form bilayers in aqueous environments, creating the foundation of all biological membranes. Understanding why phospholipids are amphipathic requires examining their molecular structure, chemical behavior, and functional implications in living systems.

What Does Amphipathic Mean?

The term \"amphipathic\" comes from the Greek words *amphi*, meaning \"both,\" and *pathos*, meaning \"feeling\" or \"suffering.\" In chemistry and biology, an amphipathic molecule has two distinct regions: one that interacts favorably with water (hydrophilic), and another that does not (hydrophobic). These molecules are essential in biological systems because they enable the formation of organized structures like micelles and lipid bilayers, which serve as barriers between different environments within and around cells.

Amphipathic molecules align themselves strategically in water-based solutions. The hydrophilic portion faces the water, while the hydrophobic part turns inward, away from it. This self-organizing behavior reduces thermodynamic instability and increases system efficiency—a principle known as the hydrophobic effect.

Molecular Structure of Phospholipids

A phospholipid consists of three main components:

- A glycerol backbone

- Two fatty acid chains (tails)

- A phosphate group attached to a polar head group

The glycerol molecule serves as the structural anchor. Attached to it are two long hydrocarbon chains derived from fatty acids. These tails are nonpolar and repel water—they are hydrophobic. On the opposite end of glycerol is the phosphate group, which is negatively charged and often linked to additional polar molecules such as choline, serine, or ethanolamine. This entire head region is highly polar and readily forms hydrogen bonds with water, making it strongly hydrophilic.

Fatty Acid Tails: Hydrophobic Properties

The two fatty acid chains vary in length and saturation. Saturated tails are straight and pack tightly, contributing to membrane rigidity. Unsaturated tails contain kinks due to double bonds, increasing fluidity. Regardless of type, these hydrocarbon chains resist interaction with water due to their lack of charge and inability to form hydrogen bonds. When exposed to water, this causes energetic instability, prompting the molecule to minimize contact between the tails and the aqueous environment.

Phosphate Head Group: Hydrophilic Properties

The phosphate group carries a negative charge, and depending on the attached group (e.g., choline), the overall head may carry a net neutral or slight positive/negative charge. Because it is polar and charged, it readily dissolves in water and participates in electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding. This makes the head group fully compatible with aqueous surroundings such as cytoplasm and extracellular fluid.

Why Are Phospholipids Amphipathic? A Functional Explanation

It is precisely this combination—the polar head and nonpolar tails—that makes phospholipids amphipathic. Their structure forces them to organize in specific ways when placed in water. Instead of dispersing randomly, they form stable arrangements that shield the hydrophobic tails from water while exposing the hydrophilic heads to it.

In bulk solution, phospholipids can form spherical structures called micelles (typically with single-tailed lipids) or, more commonly in biology, double-layered sheets known as lipid bilayers. In a bilayer, two layers of phospholipids align tail-to-tail, creating a central hydrophobic core flanked by two hydrophilic surfaces. This arrangement is the basis of all cell membranes, including the plasma membrane and organelle membranes.

“Phospholipid amphipathicity isn’t just a chemical curiosity—it’s the physical principle that enables life as we know it.” — Dr. Rebecca Lin, Molecular Biophysicist

Biological Significance of Amphipathic Phospholipids

The amphipathic nature of phospholipids underpins numerous biological functions:

- Membrane Formation: Spontaneous assembly into bilayers creates selectively permeable barriers that define cellular boundaries.

- Compartmentalization: Organelles like mitochondria, lysosomes, and the nucleus are enclosed by phospholipid membranes, allowing specialized internal environments.

- Fluid Mosaic Model Support: The bilayer acts as a fluid matrix in which proteins, cholesterol, and glycolipids move laterally, enabling dynamic cellular processes.

- Signal Transduction: Some phospholipids participate in intracellular signaling pathways; for example, phosphatidylinositol derivatives act as secondary messengers.

- Vesicle Transport: Membranes bud off to form vesicles during endocytosis and exocytosis, relying on the flexibility and self-sealing properties of phospholipid bilayers.

Real-World Example: Cell Membrane Repair

Consider a scenario where a cell experiences minor mechanical damage to its membrane. Due to the amphipathic nature of phospholipids, nearby lipids quickly reorganize to seal the breach. The hydrophobic cores avoid water exposure, driving spontaneous fusion of edges. No external energy input is required—this repair mechanism relies entirely on the inherent physicochemical properties of phospholipids. This automatic response prevents leakage of cellular contents and maintains homeostasis.

Step-by-Step: How Phospholipids Form a Bilayer in Water

- Contact with Water: Individual phospholipids are introduced into an aqueous environment.

- Initial Orientation: Molecules orient so that hydrophilic heads face water and hydrophobic tails cluster together.

- Aggregation: Lipids aggregate into small clusters to minimize tail-water contact.

- Bilayer Nucleation: Two layers begin forming, tails facing inward, heads outward.

- Expansion and Sealing: The sheet grows laterally and curves to form a closed vesicle, eliminating exposed edges.

- Stabilization: Van der Waals forces between tails and hydrogen bonding at the surface stabilize the structure.

Comparison Table: Key Features of Phospholipid Regions

| Region | Chemical Nature | Solubility in Water | Role in Membrane |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Head | Polar/charged (phosphate + organic group) | Highly soluble | Interacts with aqueous environments; provides stability |

| Hydrophobic Tails | Nonpolar hydrocarbons | Insoluble | Forms interior barrier; controls permeability |

Common Misconceptions About Amphipathic Molecules

Some learners assume that being amphipathic means a molecule splits evenly between water and oil. However, the key is not balance but duality—having separate regions with opposing affinities. Another misconception is that only phospholipids exhibit this property. In fact, other biomolecules like bile salts, detergents, and certain proteins (e.g., apolipoproteins) are also amphipathic and rely on similar principles for function.

FAQ

Can a molecule be partially amphipathic?

No. Amphipathicity is a structural feature requiring clearly defined hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains. A molecule either has both regions or it doesn't. Partial polarity doesn't qualify as amphipathic unless there's segregation of properties across distinct areas.

Are all lipids amphipathic?

No. Triglycerides, for instance, are entirely hydrophobic and store energy in fat droplets. Cholesterol is mostly hydrophobic with a small polar OH group, giving it weak amphipathic character. Only phospholipids, sphingolipids, and some glycolipids are classically amphipathic in the context of membrane formation.

Do synthetic amphipathic molecules behave like phospholipids?

Yes. Many lab-made surfactants mimic phospholipid behavior by forming micelles or bilayers. This principle is exploited in nanotechnology and pharmaceutical design, especially in creating lipid nanoparticles for mRNA vaccines.

Conclusion: Embracing the Duality of Life’s Building Blocks

The amphipathic nature of phospholipids is not merely a textbook definition—it is a cornerstone of cellular life. From the first protocells in evolutionary history to the complex signaling networks in human neurons, the ability of these molecules to self-assemble into functional barriers has enabled biological complexity. By understanding how structure dictates function at the molecular level, we gain deeper insight into the elegance of biological systems.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?