It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you hang a 100-light string across the porch, plug it in, and the first 20 bulbs glow warmly—but by light #75, they’re noticeably duller. By the end? Barely visible. You check for loose bulbs, swap out fuses, even test outlets—yet the dimming persists. This isn’t faulty wiring or cheap bulbs. It’s physics in action: voltage drop. A fundamental electrical principle that quietly governs how every incandescent, LED, and mini-light string performs—especially over distance. Understanding it doesn’t require an engineering degree. It does require knowing how electricity behaves in real-world circuits, why manufacturers design strings the way they do, and what you can (and can’t) safely do to restore full brightness.

What Voltage Drop Really Is—and Why It Happens

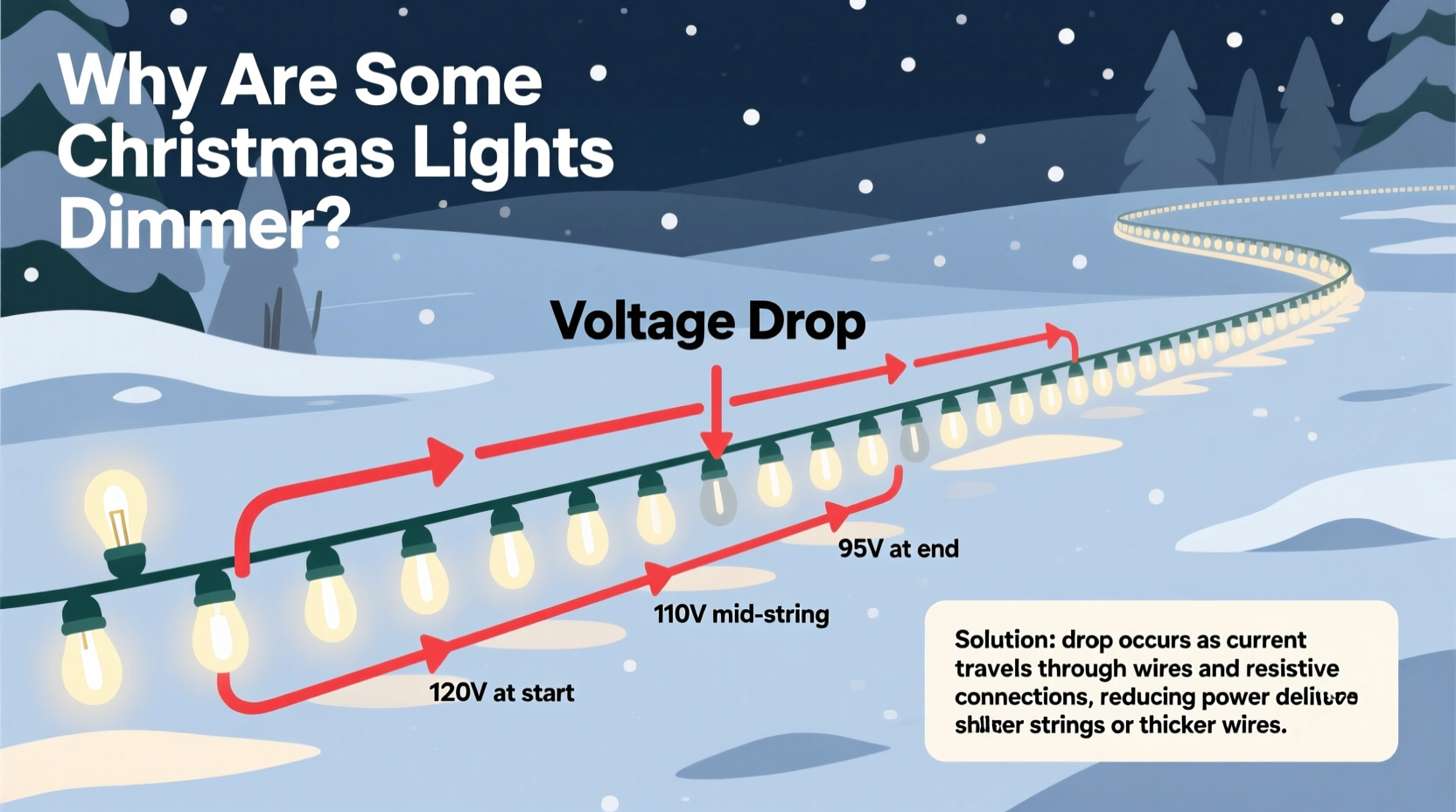

Voltage drop is the gradual reduction in electrical potential energy as current flows through resistance. In simple terms: electricity “loses pressure” moving along a wire—just like water loses pressure traveling through a long, narrow hose. Every conductor—copper wire, bulb filament, solder joint—has inherent resistance. When current passes through, energy converts to heat, lowering the voltage available downstream.

In Christmas light strings, this effect compounds with each bulb. Traditional incandescent mini-lights are wired in series: one continuous loop where current must pass through every bulb to complete the circuit. If the string has 50 bulbs rated for 2.5 volts each, the full string is designed for 125 volts (50 × 2.5 V). But because wires have resistance—and longer strings use thinner, cheaper wire—the voltage reaching bulb #45 isn’t 125 V minus losses up to that point; it’s significantly less. That lower voltage means less power delivered (P = V²/R), resulting in reduced light output and warmer (but dimmer) filaments.

LED strings behave differently—but aren’t immune. Most consumer-grade LED lights use a hybrid approach: groups of 3–5 LEDs wired in series, then those groups wired in parallel. This reduces overall sensitivity to single-point failure but doesn’t eliminate voltage drop across the main feed wires. Poor-quality copper-clad aluminum (CCA) wire—a common cost-cutting measure—has nearly 60% higher resistance than pure copper. Over a 100-foot run, that difference alone can cause a 3–4 volt drop before the first LED group even receives power.

The Four Main Culprits Behind Uneven Brightness

Not all dimming is equal—and not all causes are fixable without rewiring. Here’s what’s actually at work:

- Wire gauge and material: Thinner wire (higher AWG number) increases resistance. A 28 AWG string suffers far more drop than a 22 AWG version—even at identical lengths.

- String length and daisy-chaining: Each additional string plugged into another adds cumulative resistance. UL safety standards limit most sets to three sets max in series—not just for fire risk, but to keep voltage drop within acceptable limits.

- Bulb type and internal resistance: Incandescent bulbs have low resistance when cold but high resistance when hot. As current flows, earlier bulbs heat up faster, drawing more voltage initially and leaving less for downstream bulbs—creating a cascading dimming effect.

- Connection quality: Corroded sockets, bent pins, oxidized plug contacts, or cold solder joints introduce *additional* resistance points. These act like “speed bumps,” causing localized voltage loss that disproportionately affects later sections.

How to Diagnose Voltage Drop Yourself (No Multimeter Required)

You don’t need professional tools to spot voltage drop patterns. Observe these telltale signs:

- Directional dimming: Consistent decrease from plug-in end to far end—not random or clustered.

- Worsening with extension cords: Adding a 50-ft outdoor-rated cord makes dimming dramatically worse, especially if it’s 16 AWG or thinner.

- Cool-to-warm gradient: Touch bulbs gently (unplugged, of course). Earlier bulbs feel warmer after 10 minutes; later ones stay cool—indicating less current flow and lower power dissipation.

- Improved performance when shortened: Cutting off the last 20 bulbs (if the set allows safe cutting) restores brightness to the remaining section.

For precise diagnosis, a multimeter is ideal—but here’s a practical alternative: use a known-good string of identical specs as a benchmark. Plug both into the same outlet, side by side. If only one dims progressively, the issue lies in that string’s construction—not your home’s wiring.

Solutions That Work—And Ones That Don’t

Fixing voltage drop requires matching the solution to the root cause. Some popular “hacks” make things worse—or create hazards.

| Approach | Effectiveness | Risk Level | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using heavier-gauge extension cords (12 or 14 AWG) | High | Low | Reduces feed-wire resistance significantly. Best for long runs to trees or garages. |

| Daisy-chaining fewer strings (1–2 instead of 3) | High | Low | Respects manufacturer voltage budgets. Often doubles perceived brightness. |

| Switching to commercial-grade LED strings with copper wire | Very High | Low | Look for “pure copper” or “22 AWG copper” in specs—not “copper-clad.” |

| Adding a 120V-to-12V transformer + low-voltage LED system | Very High | Moderate (requires installation) | Eliminates line-voltage drop entirely. Ideal for permanent displays. |

| “Boosting” voltage with a variac or dimmer | None | High | Overvoltage burns out bulbs, voids UL listing, and risks fire. |

| Twisting wires together or bypassing sockets | None | Critical | Creates short circuits, overheating, and violates electrical code. |

Real-World Case Study: The Community Tree Project

In 2022, the town of Maple Hollow installed synchronized LED lights on its 65-foot heritage oak. Volunteers used 12 identical 35-ft strings rated for “up to 3 in series.” They daisy-chained all 12—assuming “up to 3” meant per outlet, not per circuit. The result: brilliant lights on the lowest 10 feet, fading to amber glow at 30 feet, and near-black above 45 feet. An electrician measured 108 V at the first string’s input—and just 92 V at the 12th string’s entry point. Total drop: 16 volts. After reconfiguring into four independent 3-string circuits fed from separate GFCI outlets (spaced evenly around the trunk), voltage at every string input stayed above 114 V. Brightness became uniform—and energy consumption dropped 11% due to reduced resistive heating in undersized wire.

The lesson wasn’t about buying “better” lights—it was about respecting the physics baked into their design.

Expert Insight: What Engineers Design Into Light Strings

“Manufacturers don’t ‘forget’ about voltage drop—they budget for it. A typical 100-light incandescent set is designed so bulb #100 receives ~90% of nominal voltage. That’s why it looks 20–25% dimmer, not 50%. But when you exceed recommended string counts or use marginal extensions, you step outside that engineered margin—and physics takes over.” — Rafael Mendoza, Electrical Engineer, Holiday Lighting Standards Consortium

This explains why “cheap” lights often dim more severely: they use tighter voltage tolerances and lower-cost materials, shrinking the safety margin. Premium strings may include thicker bus wires, lower-resistance connectors, or even built-in voltage-regulating ICs in high-end LED models—pushing usable length further before perceptible drop begins.

Actionable Checklist: Optimize Your Display This Season

Follow these steps before hanging a single bulb:

- ✅ Count your strings: Never exceed the manufacturer’s maximum daisy-chain rating—check the tag, not the box art.

- ✅ Measure total wire path: Include extension cords. For runs over 50 ft, use 14 AWG or heavier outdoor-rated cord.

- ✅ Start fresh at outlets: Feed separate sections from different GFCI-protected outlets rather than chaining.

- ✅ Test brightness directionally: Plug in one string, walk from plug to end—note where dimming begins. That’s your effective “budget” length.

- ✅ Inspect connections: Clean metal contacts with isopropyl alcohol and a soft brush; replace cracked or discolored sockets.

- ✅ Choose copper over CCA: If buying new, verify wire material in specifications—not marketing copy.

FAQ: Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

Can I fix voltage drop by adding a capacitor or resistor?

No—and doing so is dangerous. Capacitors store energy but don’t regulate voltage under load. Resistors waste power as heat and worsen overall efficiency. Neither addresses the core issue: resistance in conductors. Only reducing resistance (thicker wire, shorter runs) or increasing supply voltage at the source (via proper transformers) solves it safely.

Why do newer LED strings still dim—even though they use less power?

Lower wattage doesn’t mean lower current demand at the *input*. A 48-watt LED string drawing 0.4A at 120V still experiences voltage drop across wire resistance (Vdrop = I × R). Since R depends on wire length and thickness—not bulb technology—the drop remains. What changes is tolerance: LEDs maintain brightness over a wider voltage range than incandescents, so dimming appears more sudden when the threshold is crossed.

Will using a surge protector help with dimming?

No. Surge protectors guard against voltage spikes—not sustained drop. In fact, low-quality protectors with long internal traces or undersized MOVs can *add* resistance, worsening the problem. Use only UL 1449-listed protectors with short, direct-path wiring—and never daisy-chain them.

Conclusion: Light Up With Confidence, Not Compromise

Voltage drop isn’t a flaw in your lights—it’s a predictable outcome of how electricity moves through matter. Recognizing it transforms frustration into informed control. You no longer need to guess why the top of your tree glows faintly while the base blazes. You now know it’s not magic, mystery, or manufacturing defect—it’s Ohm’s Law, unfolding exactly as expected. Armed with wire gauges, outlet strategy, and realistic expectations, you can design displays that shine evenly, operate efficiently, and last longer. Better yet, you’ll avoid the common pitfalls that turn seasonal joy into electrical headaches. This holiday season, let your lights reflect intention—not ignorance. Measure twice, plug once, and enjoy brilliance from socket to tip.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?