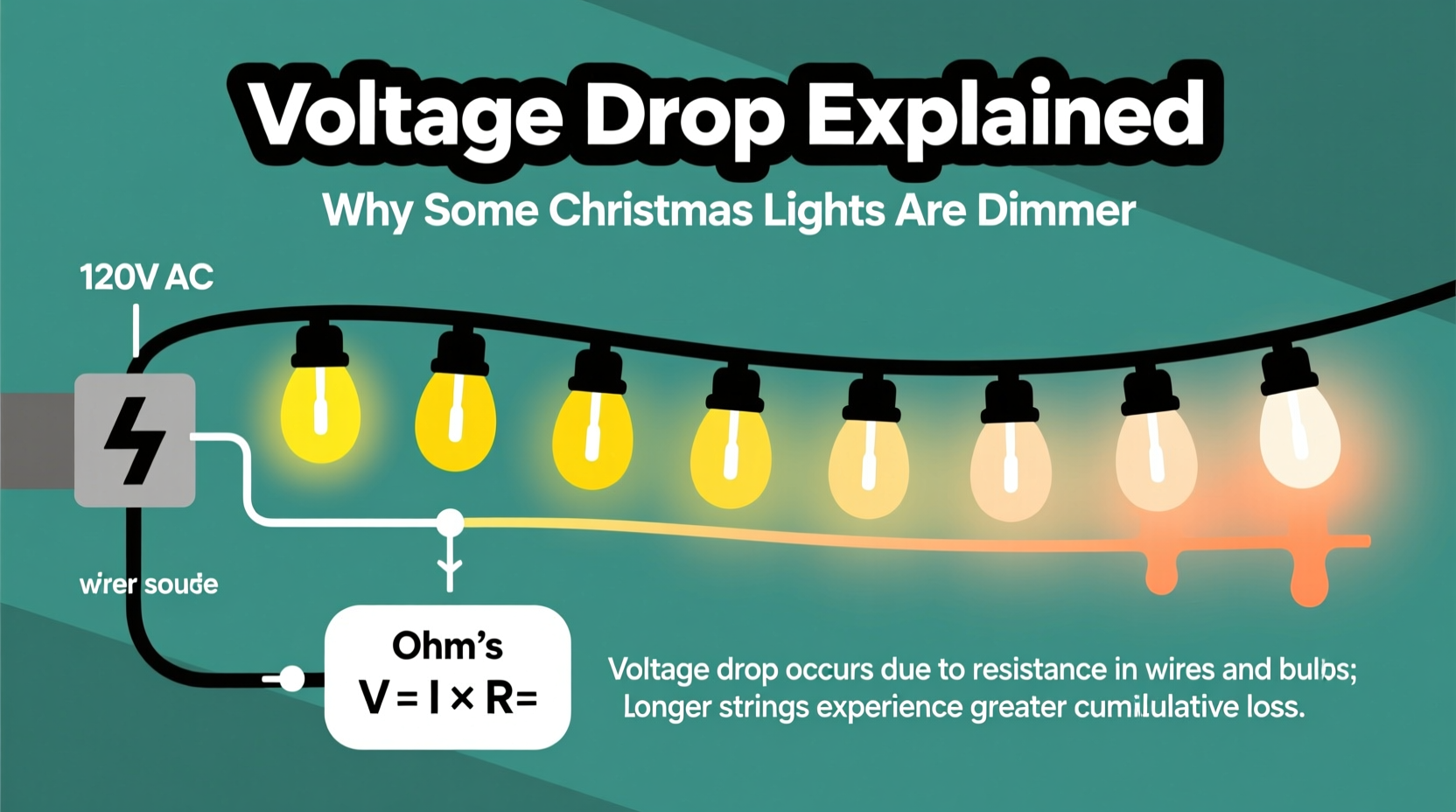

Walk into any home during the holiday season and you’ll likely spot it: a string of Christmas lights where the first few bulbs glow brightly, but the last half fade noticeably—sometimes to a dull orange or even complete darkness. It’s not faulty bulbs. It’s not poor craftsmanship. It’s physics in action—specifically, voltage drop. This phenomenon is one of the most common yet least understood issues in seasonal lighting, affecting everything from vintage incandescent mini-lights to modern LED strings. Understanding voltage drop doesn’t just satisfy curiosity—it empowers you to choose better products, troubleshoot intelligently, and install lights safely and effectively.

What Is Voltage Drop—and Why Does It Happen?

Voltage drop is the gradual reduction in electrical potential (measured in volts) as current travels through a conductor—like the copper wires inside your light string. It occurs because all real-world wires have inherent resistance, however small. According to Ohm’s Law (V = I × R), when current (I) flows across resistance (R), energy is lost as heat—and that loss appears as a drop in available voltage downstream.

In a typical 100-light incandescent string wired in series (or series-parallel), electricity enters at the plug end, powers each bulb in sequence, and exits at the far end. With every inch of wire and every filament encountered, voltage diminishes slightly. By the time current reaches the final bulbs, there may be only 85–90% of the original voltage left—just enough to make them glow weakly, if at all.

LED strings behave differently—but aren’t immune. While LEDs draw far less current, many budget LED strings use thin-gauge internal wiring and under-spec’d power supplies. The result? Same symptom, different root cause: insufficient voltage at the load end due to excessive resistance in the circuit path.

The Four Key Factors That Amplify Voltage Drop

Voltage drop isn’t random. It follows predictable patterns governed by four interrelated variables:

- Wire gauge (thickness): Thinner wires (e.g., 28 AWG vs. 22 AWG) have higher resistance per foot. Most mass-market light strings use 26–28 AWG wire—a cost-saving choice that sacrifices performance over distance.

- Circuit length: Every additional foot adds resistance. A 16.4-ft (5-m) string may show no visible dimming; a daisy-chained 100-ft run almost certainly will—even with identical bulbs.

- Current draw (amperage): Higher-wattage bulbs (e.g., 0.5W incandescents vs. 0.04W LEDs) demand more current, multiplying the voltage loss across the same resistance.

- Connection quality: Corroded plugs, loose splices, or oxidized socket contacts introduce *additional* resistance points—often concentrated near the middle or end of long runs, worsening localized dimming.

Crucially, voltage drop compounds exponentially—not linearly. Doubling the length of a string doesn’t just double the drop; it quadruples resistive losses if current remains constant (since power loss = I²R). That’s why the last 20% of bulbs often suffer disproportionately.

Incandescent vs. LED: How Technology Changes the Game

It’s tempting to assume “LED = no dimming.” Reality is more nuanced. Here’s how the two technologies compare:

| Feature | Traditional Incandescent Strings | Modern LED Strings |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Wiring | Series-parallel (e.g., 50 bulbs split into 10 groups of 5 in series) | Often series-wired with built-in current regulators—or parallel with integrated drivers |

| Voltage Sensitivity | High: Filaments require precise voltage (e.g., 2.5V per bulb in a 120V/50-bulb string). ±10% drop causes 30%+ brightness loss. | Lower—but not zero: Most LEDs operate on constant-current drivers. However, cheap units cut corners—using undersized wires and minimal regulation. |

| Dimming Pattern | Gradual fade from start to finish; entire string may go dark if one bulb fails (in true series sections) | Often “all-or-nothing” if driver fails—but mid-string dimming signals poor design or overloaded supply |

| Average Voltage Drop @ 50 ft | 8–12 V loss (7–10% of 120V) | 3–7 V loss (2.5–6%), but driver inefficiency can compound effect |

Note: Many “commercial-grade” LED strings specify “low-voltage-drop design”—meaning thicker internal wiring (22–24 AWG), redundant return paths, or distributed micro-drivers. These aren’t marketing fluff. They’re engineering responses to a real limitation.

A Real-World Example: The Garage Eave Project

Mark, a homeowner in Ohio, installed three 33-ft LED light strings along his garage eaves—daisy-chained end-to-end using manufacturer-approved connectors. He used a single 120V outlet and a heavy-duty outdoor-rated extension cord. The first string glowed evenly. The second showed mild dimming on its last 10 bulbs. The third? Only the first 15 bulbs lit at full brightness; the remaining 35 emitted a faint amber glow, barely visible after dusk.

He assumed defective bulbs—replaced five. No change. Then he measured voltage: 120.3V at the outlet, 117.1V at the input of String #1, 112.8V at String #2’s input, and just 105.6V at String #3’s plug. That 14.7V total drop exceeded the LED driver’s minimum operating threshold (108V). The fix wasn’t replacement—it was reconfiguration. Mark split the load: two strings on one outlet (fed separately via a weatherproof splitter), and the third on a second nearby outlet. All strings now run at full brightness, with voltage never dropping below 116.2V at any point.

This case underscores a critical truth: voltage drop isn’t about “bad lights.” It’s about respecting the physics of the circuit you’ve built.

How to Diagnose and Fix Voltage Drop—A Step-by-Step Guide

Don’t guess. Measure, analyze, and act. Follow this proven sequence:

- Verify outlet voltage: Use a multimeter at the receptacle (no load). Should read 114–126V. If below 114V, consult an electrician—your home wiring may be overloaded or degraded.

- Measure under load: Plug in *one* string and measure voltage at its input connector. Compare to outlet reading. A drop >2V indicates marginal wiring or a failing outlet.

- Trace the chain: For daisy-chained strings, measure voltage at the input of each subsequent string. Note the cumulative drop. If loss exceeds 3V between adjacent strings, inspect connectors for corrosion or bent pins.

- Check wire gauge: Cut a tiny slit in the insulation near the plug (safely, with power off). Use a wire gauge tool or caliper. Anything thinner than 24 AWG warrants caution for runs over 25 ft.

- Redesign the circuit: Break long chains. Use multiple outlets. Add a dedicated low-voltage transformer for LED-only setups. Or upgrade to commercial-grade strings with 22 AWG wire and active voltage compensation.

“Voltage drop is the silent killer of holiday displays. We see clients replace entire $300 light sets when a $20 multimeter and 15 minutes of measurement would’ve revealed the real issue: trying to push 120V down 150 feet of 28 AWG wire.” — Rafael Torres, Lighting Systems Engineer, HolidayPro Solutions

Prevention Checklist: Before You Hang a Single Bulb

Use this before installing any new light display:

- ☐ Confirm total wattage/amperage stays under 80% of the circuit’s capacity (e.g., ≤1440W on a standard 15A/120V circuit)

- ☐ Limit daisy-chaining to manufacturer-specified lengths—never exceed unless using commercial-grade wire and connectors

- ☐ Use outdoor-rated, 14 AWG or thicker extension cords for primary feeds—never 16 AWG “decorative” cords

- ☐ Inspect all plugs and sockets for discoloration, melting, or brittleness (signs of prior overheating/resistance)

- ☐ For permanent installations, consider low-voltage (24V DC) LED systems with local transformers—eliminates line-voltage drop entirely

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I fix dim lights by adding a booster or amplifier?

No—there’s no such thing as a “voltage booster” for standard AC light strings. Devices marketed as “brightness enhancers” are either scams or simple timers/dimmers that cannot restore lost voltage. True correction requires reducing resistance (thicker wire, shorter runs) or increasing supply capacity (more outlets, dedicated circuits).

Why do my lights dim only when it’s cold outside?

Cold temperatures increase copper wire resistance slightly (about 0.4% per °C), but the bigger factor is LED driver behavior. Many inexpensive LED drivers reduce output current in sub-freezing temps to protect components—causing apparent dimming. High-quality outdoor-rated drivers maintain consistent current down to −25°C.

Will upgrading to a higher-voltage transformer help?

Only if your system is designed for it—and most consumer strings are not. Plugging a 120V-rated string into a 130V supply risks premature bulb failure, overheated wires, and fire hazard. Never override manufacturer voltage ratings. Instead, match the supply to the load—and design the distribution to minimize drop.

Conclusion: Light Brightly, Think Physically

Voltage drop isn’t a flaw in your lights—it’s a feature of our physical world. Recognizing it transforms frustration into informed action. You stop blaming bulbs and start optimizing circuits. You choose products based on wire gauge and thermal specs—not just price or pixel count. You protect your investment, your safety, and the joy those lights bring. This holiday season, don’t just hang lights. Engineer the experience: measure voltage, respect resistance, and distribute power wisely. Your display—and your electric bill—will thank you.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?