The northern lights—known scientifically as the aurora borealis—are one of nature’s most breathtaking spectacles. Swirling ribbons of green, pink, red, and purple light dance across polar skies, captivating travelers, scientists, and dreamers alike. While their beauty is widely admired, fewer understand the complex interplay of solar wind, geomagnetism, and atmospheric chemistry that makes them possible. This article explores the science behind the aurora borealis, explaining not just how they form, but why they appear in certain places, at certain times, and in such vivid colors.

The Solar Origin of Auroras

The story of the northern lights begins 93 million miles away—at the Sun. The Sun is not a static ball of fire; it’s a dynamic star with constant nuclear fusion reactions generating immense heat and energy. One byproduct of this activity is the solar wind: a continuous stream of charged particles—mostly electrons and protons—ejected from the Sun’s upper atmosphere, or corona.

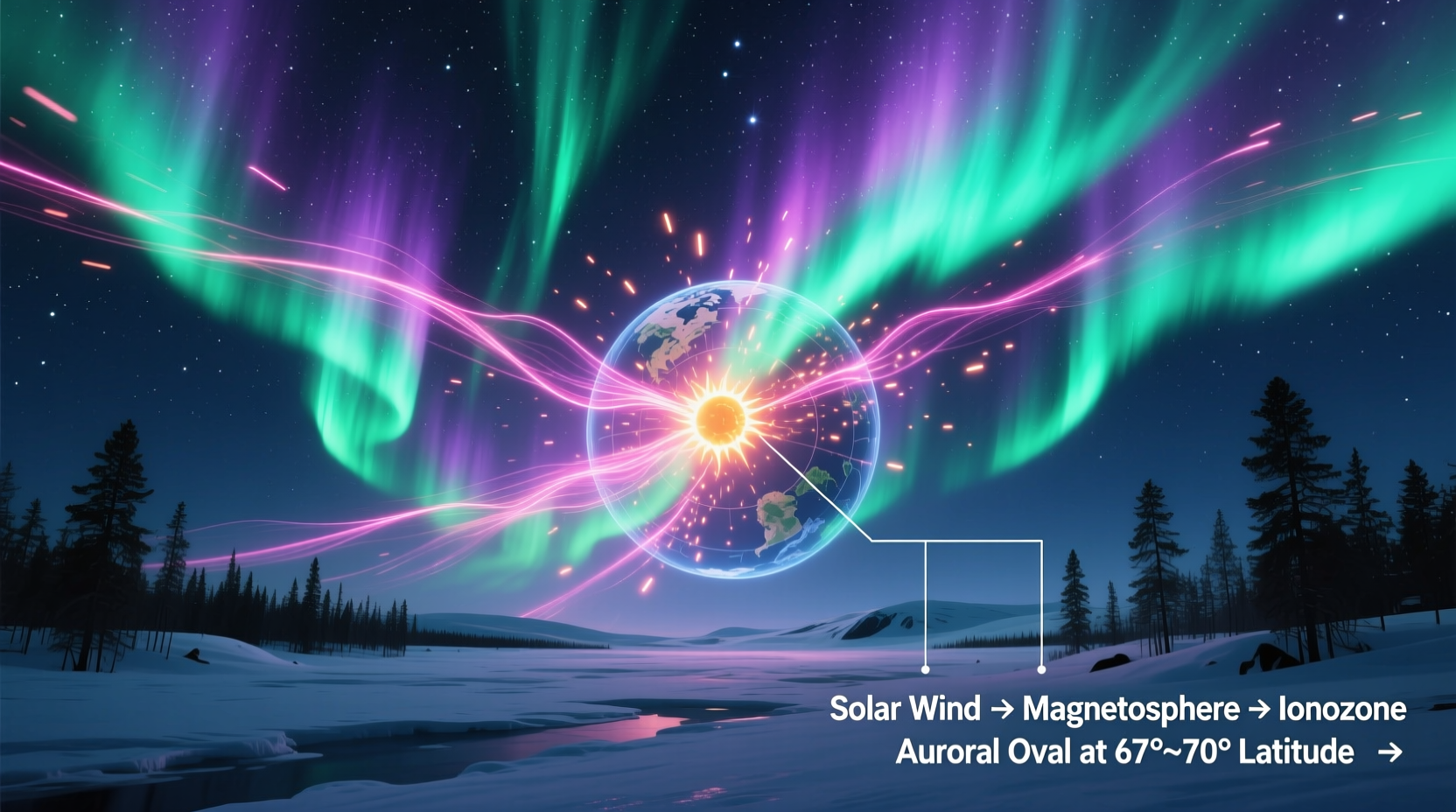

When solar activity intensifies—such as during solar flares or coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—the Sun can release billions of tons of plasma into space at speeds exceeding a million miles per hour. If Earth lies in the path of this surge, the planet’s magnetic field interacts with these high-energy particles within 1 to 3 days, setting the stage for auroral displays.

Earth’s Magnetic Field: The Invisible Shield and Conduit

Earth’s magnetosphere acts like a protective bubble, deflecting most solar wind around the planet. However, this magnetic field is weaker near the poles, creating funnel-like regions called the polar cusps. When solar particles encounter these areas, they are guided along magnetic field lines toward the North and South Poles.

As these energized particles descend into the upper atmosphere—between 50 and 400 miles above Earth—they collide with oxygen and nitrogen molecules. These collisions transfer energy to the atmospheric gases, exciting their electrons to higher energy states. When the electrons return to their normal state, they emit photons—particles of light—creating the shimmering glow we see as the aurora.

“The aurora is essentially Earth’s atmosphere glowing in response to an electric current driven by the solar wind.” — Dr. Elizabeth MacDonald, NASA Auroral Research Scientist

Colors of the Aurora: What They Reveal About the Atmosphere

The color of the aurora depends on two main factors: the type of gas being excited and the altitude of the collision. Different gases emit different wavelengths of light when energized, producing distinct hues visible from the ground.

| Gas | Altitude Range | Color Emitted | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen | 100–300 km | Green | Most common auroral color; visible in moderate solar activity. |

| Oxygen | Above 300 km | Red | Rare; appears during intense geomagnetic storms. |

| Nitrogen | Below 100 km | Blue/Purple | Seen at lower edges of active auroras. |

| Nitrogen | 100–200 km | Pink/Reddish | Mixes with green oxygen emissions for vibrant displays. |

The dominance of green in most auroral displays stems from oxygen atoms at altitudes around 100–150 km, where collision frequency and excitation efficiency are optimal. Red auroras, though rarer, often signal powerful solar storms and can sometimes be seen as far south as the Mediterranean or southern United States.

Where and When to See the Northern Lights

The aurora borealis is primarily visible in a circular zone centered around the Earth’s magnetic North Pole, known as the auroral oval. This region includes parts of Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and northern Russia. During periods of heightened solar activity, the oval expands, allowing sightings at lower latitudes.

Best viewing conditions include:

- Dark, clear skies away from city lights

- Winter months with long nights (September to March)

- High geomagnetic activity (measured by the Kp index)

- Minimal moonlight (near new moon preferred)

Step-by-Step Guide to Maximizing Your Aurora Viewing Experience

- Check the solar weather forecast – Monitor sunspot activity and CME alerts via spaceweather.com or NOAA SWPC.

- Determine your location within the auroral oval – Aim for latitudes between 65° and 72° N for consistent visibility.

- Plan around the lunar cycle – Schedule trips during a new moon or when the moon sets early.

- Arrive early and stay late – Auroras often peak between 10 PM and 2 AM local time.

- Dress appropriately – Temperatures in aurora zones can drop below -30°C; wear layered thermal clothing.

- Let your eyes adjust – Avoid phone screens and white lights; use red-light flashlights to preserve night vision.

Mini Case Study: A Photographer’s Night in Tromsø

In February 2023, landscape photographer Lena Madsen traveled to Tromsø, Norway, hoping to capture the northern lights. Despite cloudy forecasts, she ventured out based on a Kp index prediction of 6—indicating strong geomagnetic activity. By midnight, the clouds parted, and a vivid green aurora erupted overhead, shifting into crimson waves as the storm intensified.

Lena used a DSLR with a wide-angle lens, setting exposure to 15 seconds at f/2.8 and ISO 1600. She later explained, “Understanding the solar forecast gave me confidence to go out even when conditions looked poor. The aurora lasted over three hours—far longer than expected.” Her resulting image went viral, illustrating how scientific awareness enhances real-world experience.

Common Misconceptions About the Aurora Borealis

Despite growing public interest, several myths persist about the northern lights:

- Myth: Auroras are caused by reflections of sunlight off ice.

Reality: They result from charged particles colliding with atmospheric gases. - Myth: You can hear the aurora.

Reality: While some claim to hear crackling sounds, scientific consensus holds that auroras occur too high for audible transmission. Any sounds are likely psychological or environmental (e.g., frost cracking). - Myth: Auroras only happen in winter.

Reality: They occur year-round but are only visible in darkness—making winter ideal due to long nights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can the aurora borealis be predicted accurately?

Yes, short-term predictions (1–3 days) are highly reliable using satellite monitoring of solar wind speed, density, and magnetic field direction. The DSCOVR satellite provides real-time data that feeds into models used by NOAA and other agencies.

Do southern hemisphere countries see similar lights?

Yes. The southern counterpart, called the aurora australis, appears over Antarctica and is occasionally visible from southern Australia, New Zealand, Chile, and Argentina. It behaves identically to the northern lights but is less observed due to limited landmass in the southern auroral zone.

Is climate change affecting aurora visibility?

No direct link exists. Auroral frequency and intensity depend on solar cycles (approximately 11 years), not atmospheric temperature. However, increased tourism to polar regions due to accessibility may raise awareness and reported sightings.

Conclusion: Embrace the Science Behind the Spectacle

The aurora borealis is more than a pretty light show—it’s a visible manifestation of our planet’s deep connection to the Sun. From solar explosions to quantum-level interactions in the upper atmosphere, every aspect of the phenomenon reveals the elegance of natural physics. Understanding why auroras occur doesn’t diminish their wonder; it enhances it.

Whether you're planning a trip to see them firsthand or simply gazing upward in quiet awe, let scientific curiosity deepen your appreciation. The northern lights remind us that Earth is part of a vast, dynamic system—one where invisible forces paint the sky in radiant color.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?