In the annals of American political history, few acts of violence have carried as much symbolic weight as the 1856 caning of Senator Charles Sumner by Representative Preston Brooks. The brutal assault inside the U.S. Capitol was not merely a personal vendetta—it was a flashpoint in the escalating national conflict over slavery. This incident laid bare the deepening divide between North and South, revealing how political discourse had deteriorated into physical confrontation. Understanding why Brooks attacked Sumner requires examining the volatile climate of antebellum America, the personalities involved, and the broader implications of the event on the road to civil war.

The Immediate Trigger: \"The Crime Against Kansas\" Speech

The direct cause of the attack was a fiery speech delivered by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner on May 19–20, 1856, titled \"The Crime Against Kansas.\" In this address, Sumner condemned the expansion of slavery into the Kansas Territory and denounced pro-slavery forces attempting to impose a slaveholding regime through fraud and violence. His rhetoric was sharp, moralistic, and deeply personal.

Sumner reserved particular scorn for Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina, a relative of Preston Brooks and a staunch defender of slavery. He mocked Butler’s speech impediment and used degrading imagery, likening his devotion to slavery to a \"mistress\" and a \"harlot.\" To many Southerners, such language was not just offensive—it was an unforgivable insult to Southern honor and dignity.

“Senator Sumner did not merely oppose a policy; he ridiculed a man, and in doing so, offended an entire culture that placed immense value on personal honor.” — Dr. James McPherson, Civil War Historian

Preston Brooks: A Man of Southern Honor

Preston Brooks, a Democratic congressman from South Carolina, viewed Sumner’s remarks as a direct affront to his family and region. As a nephew of Senator Butler, he felt personally obligated to defend his kinsman’s reputation. In the Southern code of honor, verbal insults—especially those deemed cowardly or dishonorable—were often answered with physical retribution, typically through dueling.

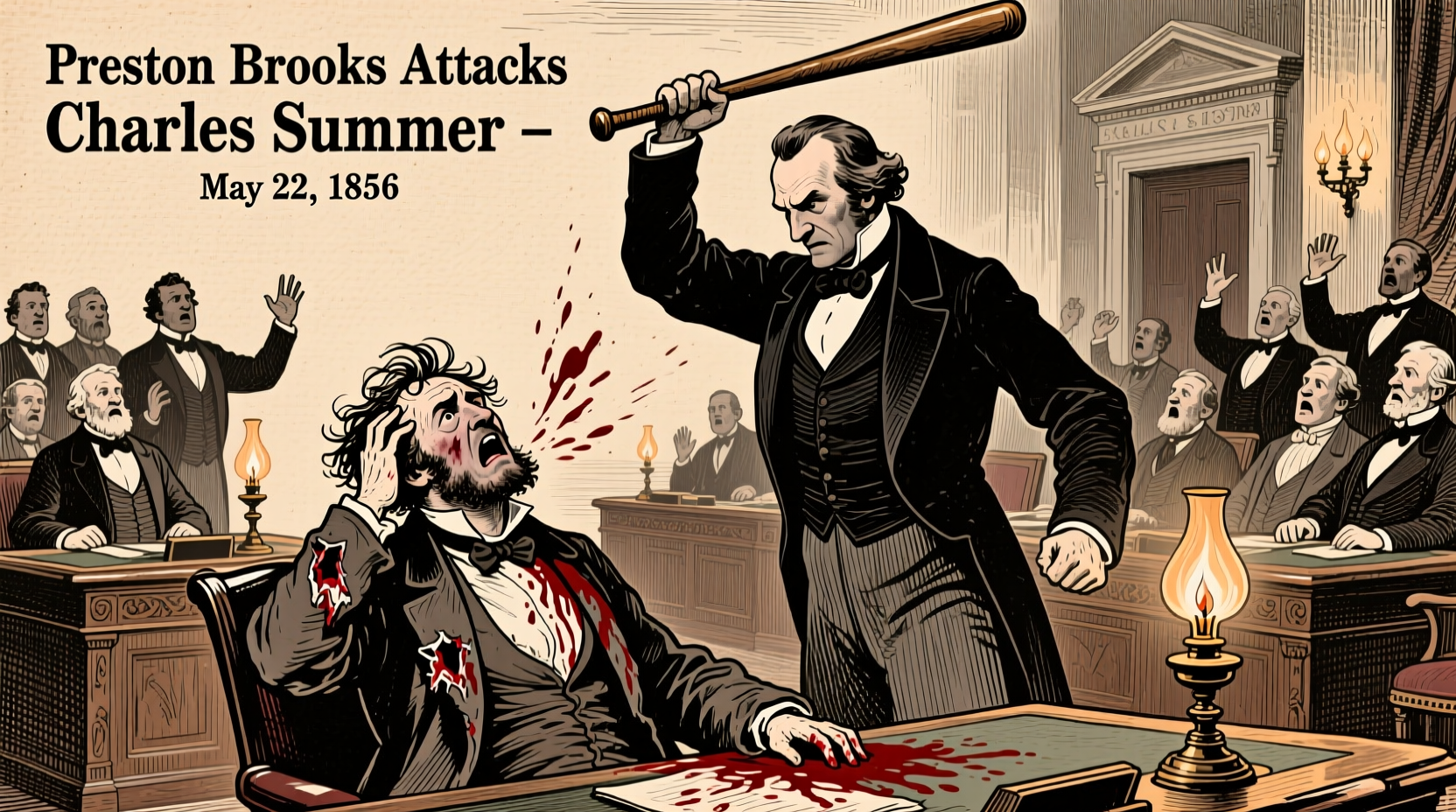

However, dueling with a Northerner like Sumner, whom Southerners considered beneath such formal traditions, was not seen as appropriate. Instead, Brooks chose a different form of punishment: a public caning. On May 22, 1856, two days after the speech, Brooks entered the Senate chamber and approached Sumner, who was seated at his desk, signing letters.

Without warning, Brooks began beating Sumner over the head with a thick gutta-percha cane. Sumner, trapped under his bolted-down desk, struggled to rise but was repeatedly struck. The attack lasted nearly a full minute until Brooks’s cane broke and he stopped, exhausted. Sumner suffered severe head trauma and was unable to return to the Senate for three years.

Reactions Across the Nation: Polarization Intensifies

The response to the caning was sharply divided along regional lines. In the North, the attack was widely condemned as barbaric and emblematic of Southern tyranny. Newspapers published graphic accounts and illustrations of the assault. Sumner became a martyr for the anti-slavery cause, and donations poured in to support him. The Republican Party leveraged the incident to argue that slaveholders were willing to use violence to silence free speech.

In the South, however, Brooks was hailed as a hero. Many praised his defense of Southern honor. He received hundreds of replacement canes in the mail, some inscribed with messages like “Hit him again.” The Charleston Mercury declared, “Good work, Preston Brooks!” Rather than face serious consequences, Brooks resigned from Congress only briefly and was quickly re-elected by his constituents.

This divergence in reaction underscored the profound moral and cultural chasm between North and South. What one side saw as a criminal assault, the other celebrated as righteous justice.

A Timeline of Key Events Leading to the Assault

- 1854: The Kansas-Nebraska Act passes, allowing settlers to decide on slavery via popular sovereignty.

- 1855: Pro- and anti-slavery factions flood Kansas, leading to violent clashes known as \"Bleeding Kansas.\"

- May 19–20, 1856: Charles Sumner delivers \"The Crime Against Kansas,\" insulting Andrew Butler and Southern values.

- May 22, 1856: Preston Brooks attacks Sumner in the Senate chamber with a cane.

- June 1856: Brooks is censured by the House but avoids expulsion; he resigns and wins re-election.

- 1857: Sumner returns to the Senate, symbolizing Northern resilience.

Broader Implications: A Nation Divided

The caning of Charles Sumner was more than a congressional scandal—it was a catalyst in the breakdown of national unity. It demonstrated that political debate could no longer contain the passions surrounding slavery. The federal government, once a forum for compromise, was now a battleground where words could provoke bloodshed.

The incident also revealed the fragility of democratic norms. Brooks faced no meaningful legal penalty. Though the House of Representatives expelled him, his swift re-election signaled widespread Southern approval of political violence in defense of slavery and honor.

Moreover, the attack contributed to the collapse of the Whig Party and strengthened the newly formed Republican Party, which positioned itself as the defender of free labor, free speech, and Northern values. By 1860, the divisions exposed in 1856 would culminate in Abraham Lincoln’s election and the secession of Southern states.

| Aspect | Northern View | Southern View |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation of Brooks | Vindictive, uncivilized | Honorable, justified |

| Sumner's Speech | Freedom of expression | Insult to Southern dignity |

| The Caning | Criminal assault | Righteous punishment |

| Brooks’ Re-election | Alarming endorsement of violence | Democratic affirmation of honor |

| Impact on National Unity | Deepened mistrust of the South | Strengthened regional solidarity |

Mini Case Study: The Symbolism of the Cane

The weapon Brooks used—a heavy walking cane made of gutta-percha—became a powerful symbol. In the North, it represented the brute force of slave power silencing dissent. Editorial cartoons depicted Brooks as a barbarian, swinging his cane over a broken Liberty Bell or a Constitution in tatters.

In the South, the cane was transformed into a relic of honor. When Brooks died less than a year later in January 1857, many mourned him as a patriot. Schools were named in his honor, and decades later, statues and streets commemorated his actions. The very object of violence became a token of regional pride, illustrating how deeply entrenched the defense of slavery had become in Southern identity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Preston Brooks ever punished for the attack?

Brooks was tried in a District of Columbia court and fined $300, but he avoided jail time. The U.S. House of Representatives voted to expel him, but rather than wait, he resigned. He was quickly re-elected by his South Carolina constituents, signaling strong regional support for his actions.

Did Charles Sumner recover from the attack?

Sumner suffered from chronic pain, headaches, and post-traumatic stress for years. He spent time recovering in Europe and did not return to his Senate duties until December 1859. Despite his injuries, he remained an influential voice in the anti-slavery movement and served in the Senate until his death in 1874.

How did the caning affect the abolitionist movement?

The attack galvanized anti-slavery sentiment in the North. Abolitionists used the event to highlight the moral corruption of the slaveholding class, arguing that their willingness to resort to violence proved they could not be trusted within a democratic republic. The incident helped unify disparate anti-slavery factions under a common cause.

Conclusion: A Warning from History

The caning of Charles Sumner by Preston Brooks stands as a stark reminder of what happens when political discourse collapses into personal vengeance. It was not an isolated act of madness but a product of a society tearing itself apart over the issue of human bondage. The divergent reactions—martyrdom in the North, heroism in the South—show how two sections of the same nation could interpret the same event in completely opposite ways.

Today, as political polarization rises and threats of violence occasionally surface in public life, the Sumner-Brooks incident offers a sobering lesson. Democracies depend on mutual respect, even amid disagreement. When insults replace dialogue and violence supplants debate, the foundations of self-government begin to crumble.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?