Every December, millions of households string up festive lights—only to discover, mid-unboxing, that the plug doesn’t fit their outlet. It’s not a manufacturing error or oversight. It’s physics, policy, and history converging in a tiny plastic housing. Christmas lights are among the most globally traded seasonal goods, yet they rarely cross borders without compatibility friction. The reason lies not in whimsy or branding—but in fundamental electrical infrastructure, national safety regulations, and decades of divergent standardization. Understanding these differences isn’t just about convenience; it’s about safety, compliance, and avoiding fire hazards, equipment damage, or costly returns.

The Core Drivers: Voltage, Frequency, and Safety Philosophy

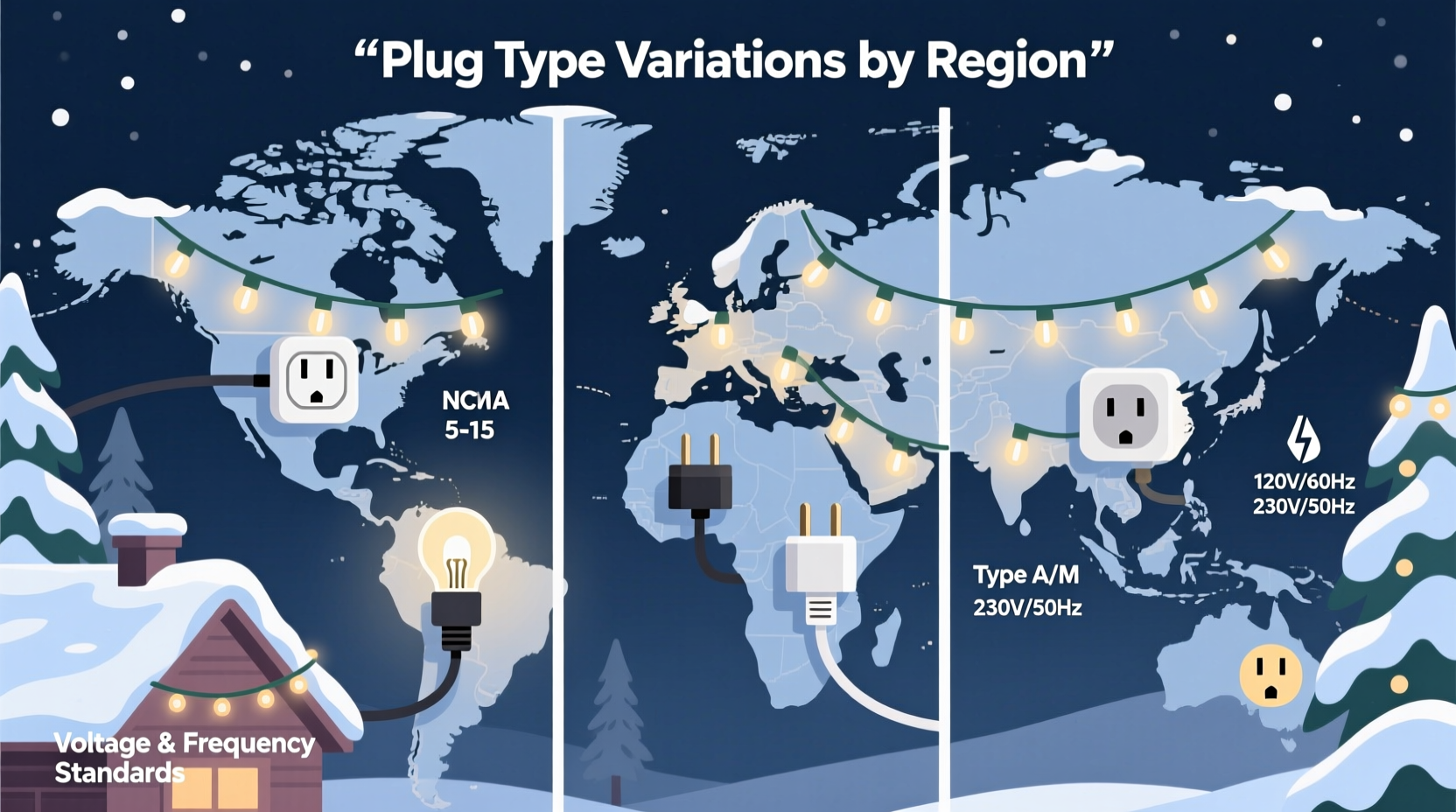

At the heart of regional plug variation are three interlocking technical realities: nominal supply voltage (e.g., 120 V vs. 230 V), alternating current frequency (50 Hz vs. 60 Hz), and distinct regulatory philosophies on consumer protection. These aren’t arbitrary choices—they reflect historical infrastructure decisions made as nations electrified in the early-to-mid 20th century.

In North America, the U.S. and Canada standardized on 120 V at 60 Hz, partly influenced by Thomas Edison’s early DC systems and later optimized for incandescent lighting efficiency and motor performance. Europe, by contrast, adopted 230 V at 50 Hz—initially driven by German engineering priorities and the need for longer-distance transmission with lower current (and thus reduced copper costs). Japan uniquely straddles both worlds: eastern regions (including Tokyo) use 100 V/50 Hz, while western regions (including Osaka) use 100 V/60 Hz—a legacy of competing pre-war power companies.

These voltage differences directly impact light design. A string rated for 120 V will overheat and fail catastrophically if plugged into a 230 V circuit—even with an adapter. Conversely, a 230 V string on 120 V may not illuminate at all or will glow dimly and erratically. Crucially, plug shapes themselves evolved not merely as physical connectors but as *safety enforcers*: grounding configurations, pin dimensions, insulation depth, and insertion force were engineered to prevent accidental contact, overheating, and incorrect voltage application.

How Regional Standards Shaped Plug Design

Plug types didn’t emerge from vacuum—they were codified through national and regional bodies with specific safety mandates. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) publishes global reference standards (e.g., IEC 60884), but adoption is voluntary. What followed was a patchwork of national implementations:

- North America (Type A/B): NEMA 1-15 (ungrounded) and NEMA 5-15 (grounded) plugs dominate. Their flat, parallel blades allow compact, low-cost manufacturing—ideal for mass-market seasonal goods. Grounding pins prevent shock when moisture or damaged insulation compromises the string.

- United Kingdom & Ireland (Type G): The iconic three-rectangular-pin plug includes a built-in fuse (typically 3 A or 13 A), reflecting the UK’s “fuse-first” safety doctrine. This design assumes fault currents must be interrupted *at the plug*, not just at the circuit breaker—critical for long, daisy-chained light strings prone to overload.

- Europe (Type C/F “Schuko”): Two-round-pin plugs with side grounding clips (Type F) or recessed sockets (Type C) emphasize high-contact surface area and robust grounding. Germany’s VDE certification requires stringent flame-retardant housing and wire insulation—non-negotiable for indoor holiday decor near trees and fabrics.

- Australia/New Zealand (Type I): Slanted, flat pins with active/neutral asymmetry prevent reverse polarity—a major concern given Australia’s strict AS/NZS 60598.2.20 standard for decorative lighting, which mandates higher IP ratings for outdoor use.

- Japan (Type A): Physically identical to North American Type A, but with critical voltage nuance: Japanese outlets deliver only 100 V, making them incompatible *electrically* with most U.S. 120 V strings despite plug compatibility. Many Japanese light sets include internal voltage regulators to handle minor fluctuations.

This fragmentation isn’t bureaucratic inertia—it’s deliberate risk mitigation. As Dr. Lena Hoffmann, Senior Electrical Safety Engineer at TÜV Rheinland, explains:

“Plug standardization is never just about convenience. It’s the last physical barrier between a consumer and lethal current. When a country mandates fused plugs, insulated pins, or mandatory grounding for low-voltage decorative lighting, it’s responding to decades of incident data—overheated wires, tree fires, electrocutions in wet gardens. The ‘right’ plug is the one that makes unsafe usage physically difficult.”

A Real-World Consequence: The 2022 EU Import Recall

In November 2022, the European Commission issued an RAPEX alert (A12/1179/22) recalling over 42,000 units of LED Christmas light strings imported from China. The lights used non-compliant Type C plugs with insufficient insulation thickness and missing CE marking. Crucially, internal wiring lacked the mandated 0.75 mm² cross-section required under EN 60598-2-20 for sustained outdoor operation. When tested at 230 V, multiple units exceeded surface temperature limits by 28°C—posing ignition risk near dry pine boughs.

The root cause wasn’t fraud or negligence alone. It was a misalignment between production assumptions (many factories default to “universal” Type C molds) and EU-specific thermal and mechanical testing protocols. Retailers had sourced lights labeled “EU compliant” based on plug shape alone—ignoring that compliance requires full-system validation: plug, cord, controller, and LED driver. This case underscores a hard truth: plug type is the visible tip of a deep regulatory iceberg.

Practical Comparison: What Works Where—and What Doesn’t

Travelers, expats, and small retailers often assume “adapters solve everything.” They don’t. Below is a reality-check table clarifying compatibility across key markets—not just plug shape, but functional viability.

| Region | Standard Plug | Supply Voltage / Frequency | Is a Physical Adapter Sufficient? | Critical Compliance Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States & Canada | Type A/B (NEMA) | 120 V / 60 Hz | No — only if light is rated for 120 V | UL 588 (Standard for Seasonal and Holiday Decorations) |

| United Kingdom & Ireland | Type G | 230 V / 50 Hz | No — fused plug + correct voltage essential | BS EN 60598-2-20 |

| Germany, France, Netherlands | Type F (Schuko) | 230 V / 50 Hz | No — Schuko requires grounding clips; simple Type C adapters lack this | VDE 0700-2-20 |

| Australia & New Zealand | Type I | 230 V / 50 Hz | No — slanted pins prevent safe insertion into non-Type I sockets | AS/NZS 60598.2.20 |

| Japan | Type A | 100 V / 50 Hz (East) or 60 Hz (West) | Risky — same shape ≠ same voltage tolerance; many U.S. strings overheat at 100 V | JIS C 8201-2-20 |

Note: “No” in the “Is a Physical Adapter Sufficient?” column means using only a passive adapter creates unacceptable risk—regardless of how neatly it fits.

Actionable Steps for Safe, Compliant Use

Whether you’re decorating a home abroad, sourcing lights for resale, or troubleshooting a malfunctioning string, follow this sequence—never skip steps.

- Identify the light’s input rating: Locate the label on the plug housing, controller box, or original packaging. Look for “Input: XX–YY V ~” or “Rated Voltage: ___ V”. If it shows only one value (e.g., “120 V”), it is not universal.

- Confirm local supply specs: Use a multimeter or consult your utility provider. Don’t trust wall labels—older buildings may have ungrounded or miswired outlets.

- Match plug type to socket standard: Verify physical compatibility *and* grounding capability. Type C plugs inserted into Type F sockets without grounding clips violate EU law.

- Check for certification marks: UL (U.S.), CE + notified body number (EU), RCM (Australia), PSE (Japan). Absence doesn’t always mean unsafe—but absence *plus* unknown origin strongly suggests non-compliance.

- Test before full deployment: Plug in for 15 minutes. Feel the plug, controller, and first 30 cm of cord. If any component exceeds 40°C (warm to the touch), disconnect immediately—this indicates undersized wiring or poor heat dissipation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I cut off a foreign plug and replace it with a local one?

No—unless performed by a licensed electrician certified for decorative lighting modifications. Cutting and re-terminating voids all safety certifications, may expose live conductors, and often violates local electrical codes (e.g., NEC Article 410 in the U.S. prohibits field modification of listed lighting products). The cord’s insulation rating, conductor gauge, and strain relief are all certified as a system—not components.

Why do some “universal” LED light strings still fail overseas?

“Universal input” (e.g., 100–240 V) refers only to the driver’s ability to accept varying voltages. It does not guarantee compliance with regional safety requirements: ingress protection (IP) ratings for outdoor use, flame-retardant housing (UL 94 V-0), electromagnetic interference (EMI) limits, or mechanical durability testing. A string that works electrically in Germany may still be banned for lacking VDE-certified connectors or failing rain-simulation tests.

Are battery-powered lights exempt from these rules?

Partially. Low-voltage DC systems (<50 V) avoid mains-voltage regulations—but they’re still subject to battery safety standards (e.g., UN 38.3 for lithium cells), chemical labeling (CLP/GHS), and flammability testing for plastic housings. In the EU, even battery lights require CE marking under the Radio Equipment Directive (RED) if they include Bluetooth controllers.

Conclusion: Respect the Socket, Respect the Standard

Christmas lights are more than decoration—they’re tightly regulated electrical appliances operating in high-risk environments: near combustible materials, exposed to weather, handled by children, and often left unattended for hours. The plug isn’t a trivial detail; it’s the engineered interface between global manufacturing and local safety sovereignty. Dismissing regional differences as “just plugs” ignores the lives saved by fused UK outlets, the fires prevented by German grounding clips, and the electrocutions avoided by Australian polarity enforcement. Whether you’re hanging lights on a balcony in Berlin, a porch in Portland, or a shrine in Kyoto, taking five minutes to verify voltage, inspect certification marks, and understand what your plug truly represents transforms seasonal joy into responsible celebration. Don’t let convenience override caution—your tree, your home, and your family deserve the assurance that every connection is intentional, tested, and trusted.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?