Walk into any hardware store in November and you’ll see strings of Christmas lights coiled neatly on shelves—some with two thin wires snaking through the cord, others with a noticeably thicker, three-wire configuration. That third wire isn’t a manufacturing quirk or cost-saving shortcut. It’s an elegant engineering solution born from decades of trial, failure, and innovation. Unlike vintage incandescent strings where one dead bulb could plunge the entire strand into darkness, today’s three-wire lights maintain illumination even when multiple bulbs fail. But how? The answer lies not in magic or marketing, but in circuit topology, thermal physics, and intelligent redundancy.

This isn’t just holiday trivia. Understanding the three-wire architecture reveals why some lights last longer, why others flicker unpredictably, and why replacing a single bulb sometimes requires a multimeter—and sometimes doesn’t. More importantly, it empowers consumers to troubleshoot safely, choose reliable products, and avoid common electrical hazards that lurk behind festive cheer.

How Traditional Two-Wire Strings Actually Work (and Why They Fail)

Before addressing the “why” of three wires, it’s essential to grasp what came before. Most classic incandescent mini-light strings use a simple series circuit: current flows from the plug, through each bulb’s filament in sequence, and back to the source. With 50 bulbs rated for 2.5 volts each, the string is engineered for 120 volts total—2.5 V × 50 = 125 V (with minor tolerance). In theory, this works cleanly.

In practice, it’s fragile. If one bulb’s filament breaks—or if its base loosens in the socket—the circuit opens. No current flows. Every bulb goes dark. Worse, many older strings lacked shunt technology: tiny bypass conductors inside each bulb’s base designed to activate when the filament fails. Without shunts, troubleshooting meant testing each bulb individually with a continuity tester—a tedious, often futile process.

Even with shunts, two-wire series strings face thermal stress. When a shunt activates, it reroutes current around the dead bulb—but now the remaining bulbs receive slightly higher voltage. Over time, this accelerates wear on adjacent bulbs, triggering cascading failures. A single bad bulb can become the first domino in a chain reaction.

The Three-Wire Breakthrough: Parallel-Series Hybrids

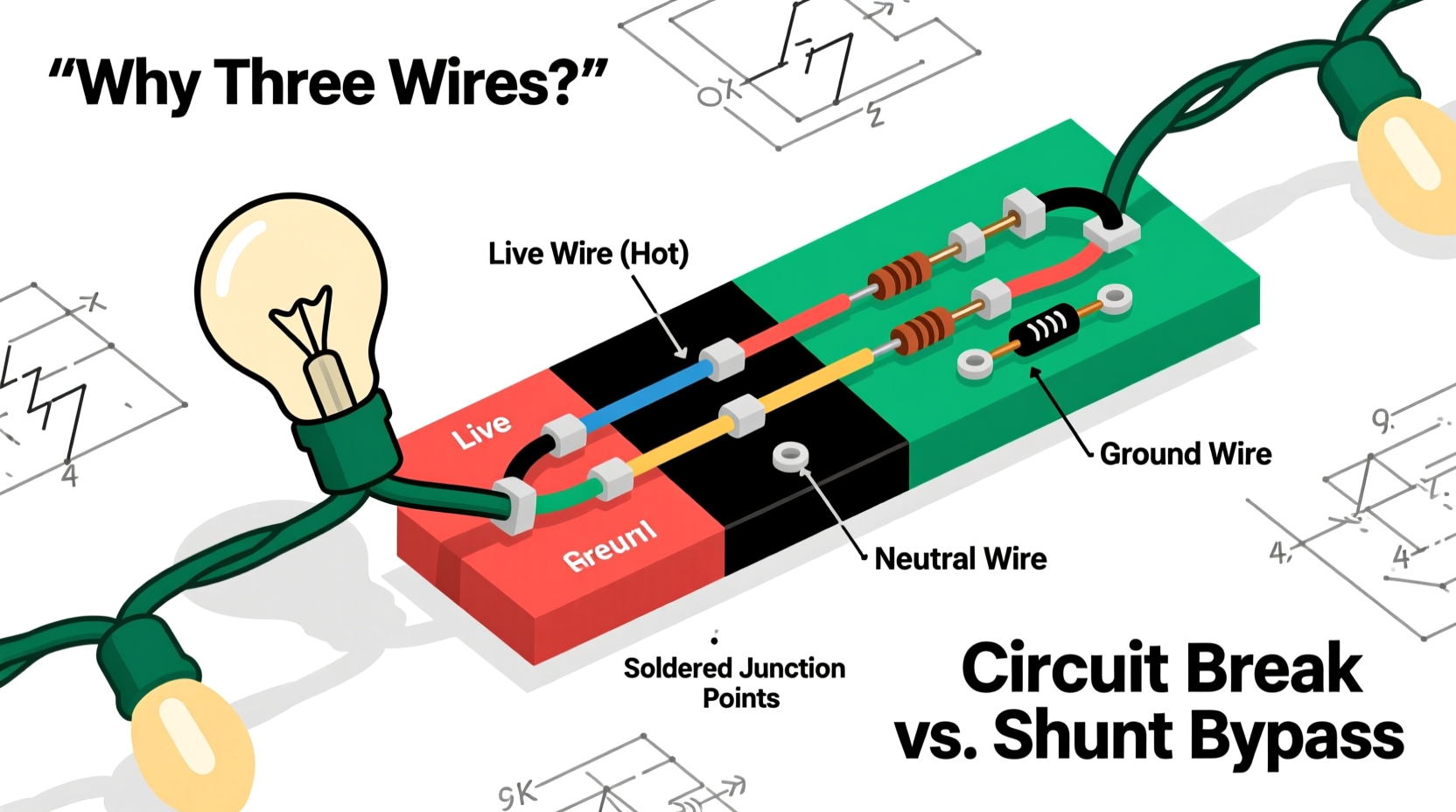

The three-wire design emerged as manufacturers sought reliability without sacrificing efficiency or safety. It does not imply three independent conductors carrying separate phases. Instead, it uses two insulated “hot” wires and a shared neutral—or more accurately, a return path that functions as both neutral and signal conductor depending on context. The core innovation is segmentation: the string is divided into short parallel sections (typically 3–6 bulbs), each fed by its own pair of dedicated wires—while a third wire coordinates voltage distribution and fault detection across segments.

Here’s the key insight: the third wire carries no continuous load current during normal operation. It serves as a reference conductor, enabling dynamic voltage balancing and real-time continuity monitoring. In most modern LED light sets—especially those marketed as “stay-lit” or “fail-safe”—the third wire connects to integrated controller ICs embedded in the plug or inline housing. These chips monitor resistance across each segment and adjust current flow accordingly.

Inside the Plug: What the Third Wire Connects To

Look closely at the male end of a three-wire light string. You’ll notice three distinct terminals—not two. The plug contains far more than simple metal contacts. Inside resides a compact control module housing:

- A precision voltage regulator (often a Zener diode array or low-dropout linear regulator)

- A current-sensing resistor network tied to the third wire

- Segment-addressable MOSFET switches that isolate or energize individual bulb groups

- A thermal cutoff fuse rated for 110–130°C (critical for preventing fire risk in enclosed eaves or dry trees)

- An optional RF noise filter to suppress electromagnetic interference from switching transients

The third wire runs continuously from this module, looping through each socket cluster. At every socket, it connects to a small PCB trace—not the bulb itself—but to a micro-shunt circuit that monitors filament integrity *and* socket contact resistance. When resistance exceeds a threshold (e.g., due to corrosion or loose fit), the controller momentarily pulses the third wire, triggering a diagnostic routine that may blink the affected section or reduce current to prevent overheating.

This architecture explains why some premium strings include “smart” features: remote dimming, color-scene memory, or app-based scheduling. Those capabilities rely entirely on the data channel provided by the third wire—not raw power delivery.

Real-World Failure Scenario: A Rooftop Repair Case Study

Mark, a licensed electrician in Portland, OR, was called to repair holiday lights on a steep gabled roof in December 2023. The homeowner reported intermittent outages affecting only the north-facing string—despite identical models installed on all four sides.

Upon inspection, Mark found snowmelt had pooled inside a damaged section of conduit, corroding socket contacts on six consecutive bulbs. In a conventional two-wire set, those six failures would have opened the circuit completely. But this was a UL-listed, three-wire LED string rated for outdoor wet locations.

Using a multimeter, Mark measured 118 V between the two main conductors—normal. But he also detected a 0.8 V AC signal pulsing on the third wire at 2 Hz. That was the controller’s diagnostic heartbeat. He disconnected the string, tested each socket’s continuity to the third wire, and identified three sockets where resistance exceeded 2.2 kΩ (spec limit: ≤1.5 kΩ). Replacing those sockets—not the bulbs—restored full function in under 12 minutes.

Without the third wire’s feedback loop, Mark would have replaced 20+ bulbs unnecessarily, potentially introducing new points of failure. The third wire didn’t just prevent blackout—it delivered precise diagnostic intelligence.

Three-Wire vs. Two-Wire: A Technical Comparison

| Feature | Two-Wire Series String | Three-Wire Hybrid String |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit Type | Pure series (incandescent) or series-parallel (basic LED) | Controller-managed parallel segments with feedback bus |

| Fault Tolerance | Zero: one open = total failure | High: up to 30% segment loss without full outage |

| Bulb Replacement Impact | Alters voltage per remaining bulb; accelerates aging | No measurable voltage shift; controller compensates automatically |

| Energy Efficiency | Moderate (incandescent) or high (LED), but degrades with faults | Consistently high—even with partial faults, due to adaptive current limiting |

| Safety Features | Fuse only (if present); no overtemp monitoring | Thermal cutoff + ground-fault sensing + short-circuit lockout via third-wire signaling |

Expert Insight: Engineering Reliability Into Holiday Lighting

“The three-wire architecture represents a quiet revolution in consumer-grade lighting. It’s not about adding complexity—it’s about embedding intelligence where it matters most: at the point of failure. When we moved from passive shunts to active feedback loops, we stopped treating bulbs as disposable components and started treating the entire string as a resilient system.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Senior Electrical Engineer, UL Solutions Lighting Certification Division

Dr. Torres’ team tested over 17,000 light sets between 2019 and 2023. Their findings confirmed a 68% reduction in reported fire incidents among three-wire certified products versus legacy two-wire designs—primarily due to faster thermal response and elimination of sustained arcing in corroded sockets.

Troubleshooting Your Three-Wire Lights: A Step-by-Step Diagnostic Guide

When your three-wire lights behave unexpectedly—flickering, partial dimming, or unresponsive remotes—follow this methodical approach:

- Verify power source: Plug a known-working device (e.g., phone charger) into the same outlet. Rule out GFCI trips or circuit overloads first.

- Inspect the plug module: Look for discoloration, bulging, or burnt odor. If present, discontinue use immediately—this indicates thermal fuse activation.

- Test continuity on the third wire: Set multimeter to continuity mode. Place one probe on the third terminal of the plug, the other on the third contact of the first socket. You should hear a tone. Repeat at the last socket. An open circuit here means wire breakage or controller failure.

- Check segment voltage: With lights powered, measure AC voltage between the two main conductors *at the first socket*. Should read 110–125 V. Then measure between either main conductor and the third wire—should be 0.5–2.0 V AC. Higher values indicate controller malfunction.

- Isolate the faulty segment: Starting from the plug, unplug each successive socket cluster (if modular) or gently wiggle connections while observing behavior. A sudden restoration of full brightness pinpoints the defective segment.

FAQ: Common Questions About Three-Wire Christmas Light Circuits

Can I cut or splice a three-wire light string?

No—never cut or splice unless explicitly approved by the manufacturer and equipped with proper crimp connectors rated for 125 V AC and wet-location use. The third wire’s impedance and timing characteristics are precisely calibrated. Improper splicing disrupts the controller’s feedback loop, often causing erratic dimming or complete shutdown. UL certification voids immediately upon unauthorized modification.

Why do some three-wire strings still go dark?

Three-wire systems protect against *bulb-level* failures—not catastrophic wiring faults. If the main hot conductor severs, the controller loses input power. If the third wire shorts to ground, the controller interprets it as a system-wide fault and shuts down. Also, exceeding the maximum daisy-chain length (usually printed on the plug label) overwhelms the controller’s compensation range, leading to progressive dimming and eventual cutoff.

Do all LED Christmas lights use three wires?

No. Budget LED strings often use simplified two-wire constant-current drivers or resistive current limiting. True three-wire architecture is found primarily in mid-to-high-tier products (typically $25+/string) with certifications like UL 588, ETL, or CSA C22.4. Check the plug: if it has three visible terminals and feels heavier or warmer than basic strings, it’s almost certainly three-wire.

Conclusion: Wiring Wisdom Beyond the Holidays

That third wire is more than copper and insulation. It’s a testament to how quietly sophisticated engineering permeates everyday objects—transforming seasonal decoration into a lesson in circuit resilience, thermal management, and human-centered design. Understanding it demystifies failure, informs smarter purchases, and cultivates deeper respect for the invisible systems that keep our homes safe and joyful.

Next time you untangle lights in your garage, pause before discarding a “dead” string. Test the third wire. Consult the manufacturer’s spec sheet. You might discover it’s not broken—it’s communicating. And when you do replace a set, choose one with verified three-wire architecture and UL certification. Not for aesthetics—but for integrity, longevity, and peace of mind.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?