Pain is universal. Every human being experiences it, yet few truly understand what it is or how it works. It’s not simply a signal from an injury site—it’s a complex, dynamic process orchestrated by the brain and nervous system. To answer the question “Why do I hurt?” we must move beyond outdated notions of pain as a direct measure of tissue damage and instead explore the intricate world of neuroscience that shapes our perception of suffering.

Modern research reveals that pain is less about physical harm and more about the brain’s interpretation of threat. This shift in understanding has profound implications for how we manage both acute injuries and chronic conditions. By examining the biological mechanisms, psychological influences, and real-world applications of pain science, we can begin to reclaim control over our bodies and lives.

The Biology of Pain: From Nerves to Brain

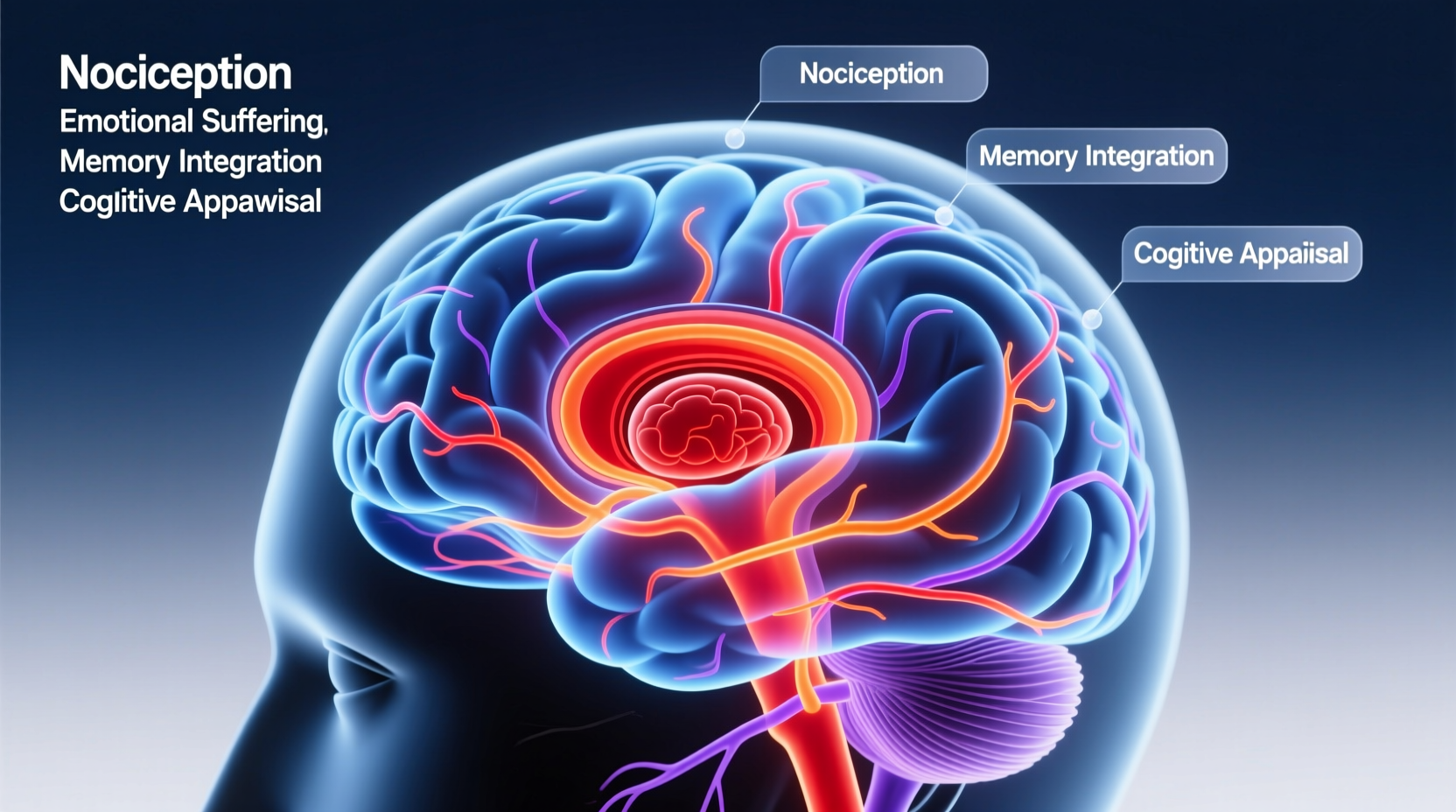

Pain begins with specialized nerve endings called nociceptors, which detect potentially harmful stimuli—such as extreme heat, pressure, or chemical changes—in tissues throughout the body. When activated, these receptors send electrical signals through peripheral nerves toward the spinal cord and ultimately to the brain.

However, this transmission is not a simple relay. The spinal cord acts as a gatekeeper, modulating signals based on context, emotion, and prior experience—a concept known as the Gate Control Theory of pain. Signals may be amplified or suppressed before they even reach conscious awareness.

Once in the brain, pain is processed across multiple regions: the somatosensory cortex (location and intensity), the insula (emotional response), and the prefrontal cortex (evaluation and decision-making). No single “pain center” exists; instead, pain emerges from a network of neural activity shaped by biology, memory, and environment.

Acute vs. Chronic Pain: A Fundamental Shift

Acute pain is typically time-limited and directly linked to tissue damage. It warns us to pull our hand from a hot stove or rest a sprained ankle. In contrast, chronic pain lasts longer than three to six months and often continues despite healed injuries. Conditions like fibromyalgia, lower back pain without structural cause, or neuropathic pain illustrate how the nervous system itself can become the source of suffering.

In chronic pain, the nervous system undergoes neuroplastic changes—essentially rewiring itself to amplify pain signals. This phenomenon, known as central sensitization, means that even light touch or normal movement can trigger intense discomfort. The brain becomes hyper-vigilant, interpreting benign inputs as threats.

“Pain is not a measure of tissue damage. It is a prediction by the brain about the level of danger.” — Dr. Lorimer Moseley, Professor of Neuroscience and Clinical Pain Specialist

Psychological and Emotional Influences on Pain

Emotions significantly shape how we feel pain. Stress, anxiety, depression, and fear activate the same limbic pathways involved in pain processing. For example, someone under high stress may experience headaches or muscle tension not due to physical strain but because their nervous system is primed for threat detection.

Conversely, positive emotions, distraction, and feelings of safety can reduce pain perception. Soldiers injured in battle sometimes report no pain until after combat ends, illustrating how context alters experience. Similarly, placebo effects demonstrate that belief alone can modulate pain through endogenous opioid release.

This mind-body connection underscores why psychological therapies—such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness—are increasingly integrated into pain management protocols.

Do’s and Don’ts in Managing Pain Perception

| Do | Avoid |

|---|---|

| Maintain regular physical activity within tolerance | Fearing all movement as harmful |

| Practice relaxation techniques like deep breathing | Isolating yourself during flare-ups |

| Seek education about your pain condition | Relying solely on passive treatments (e.g., repeated scans) |

| Engage in meaningful daily activities | Catastrophizing minor sensations |

Real Example: Living with Chronic Back Pain

Sarah, a 42-year-old teacher, began experiencing lower back pain after lifting a heavy box. Initial imaging showed mild disc degeneration—common with age—but her pain persisted for over a year despite rest, medication, and physical therapy. She avoided walking, stopped gardening, and became anxious about reinjury.

After referral to a pain specialist, Sarah learned about central sensitization. Her treatment shifted from focusing on \"fixing\" her spine to retraining her nervous system. She started graded exposure exercises, mindfulness meditation, and CBT sessions to address fear-avoidance behaviors.

Over several months, Sarah gradually increased her activity levels. While she still had occasional discomfort, her overall pain decreased significantly—not because her anatomy changed, but because her brain recalibrated its threat response.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Reinterpreting Pain

- Understand Your Pain: Learn that pain ≠ tissue damage. Read reputable sources or consult a pain educator.

- Track Triggers and Patterns: Keep a journal noting when pain flares, your mood, activity level, and thoughts.

- Reintroduce Movement Gradually: Begin with low-intensity exercise like walking or swimming, increasing slowly.

- Address Stress and Sleep: Prioritize sleep hygiene and use stress-reduction tools such as diaphragmatic breathing.

- Engage in Cognitive Reframing: Challenge unhelpful beliefs (“I’m broken”) with evidence-based perspectives (“My body is sensitive, not damaged”).

- Seek Multidisciplinary Support: Consider input from physiotherapists trained in pain science, psychologists, or pain clinics.

Expert Insight: The Role of Education in Pain Recovery

“If people understand that pain is a protective output of the brain, not a direct reflection of damage, they are more likely to engage in recovery-promoting behaviors.” — Prof. Peter O’Sullivan, Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist and Pain Researcher

Pain neuroscience education (PNE) has been shown in clinical trials to reduce pain intensity, improve function, and decrease healthcare utilization. Simply knowing *why* you hurt empowers you to respond differently.

FAQ

Can pain exist without an injury?

Yes. Phantom limb pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic regional pain syndrome all demonstrate that pain can occur in the absence of identifiable tissue damage. The nervous system generates pain based on perceived threat, not just physical input.

Why does my pain get worse some days even if I didn’t do anything different?

Pain fluctuates due to many factors beyond physical activity—including stress, fatigue, weather changes, emotional state, and attention. These influence how the brain processes incoming signals.

Is chronic pain “all in my head”?

No. Chronic pain is very real—but it originates in the brain’s processing, not necessarily in peripheral injury. Saying it’s “in your head” misunderstands neuroscience. Emotions, memories, and thoughts are physical processes in the brain that directly affect pain.

Conclusion: Rethinking Pain for Lasting Relief

To understand why you hurt is to recognize pain as a sophisticated defense mechanism, not a mere symptom. The journey from suffering to management begins with shifting perspective—from seeing pain as proof of damage to viewing it as a sign of nervous system sensitivity.

Armed with knowledge, small consistent actions, and compassionate self-awareness, individuals can reduce pain’s grip on their lives. Whether dealing with a recent injury or years of chronic discomfort, change is possible. The brain that learned to hurt can also learn to protect less—through movement, mindset, and meaning.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?