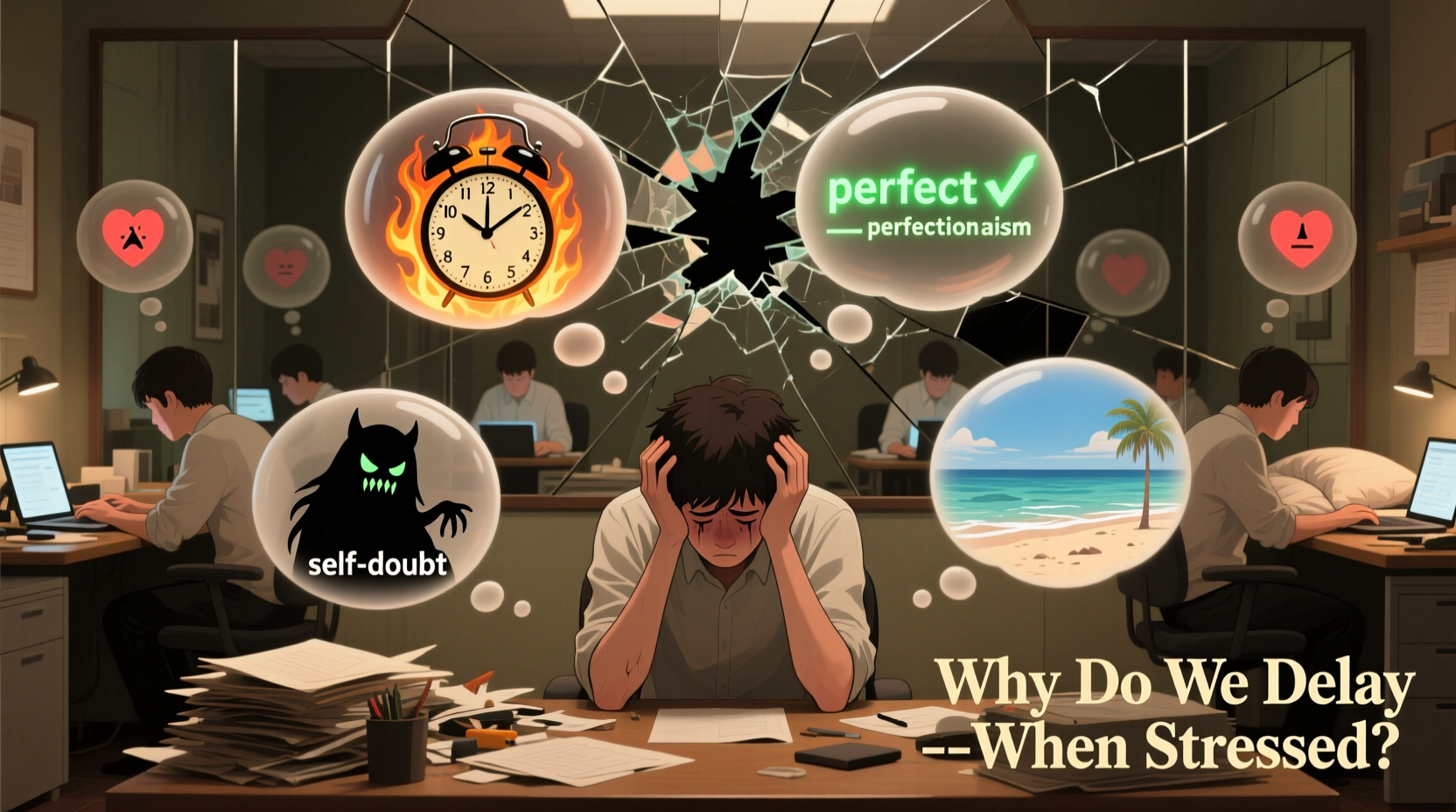

Stress is often seen as a motivator—something that sharpens focus and pushes us toward action. But in reality, many people respond to stress not by working harder, but by retreating into avoidance. The irony is palpable: the more urgent a task feels, the more likely we are to delay it. This paradox lies at the heart of modern productivity struggles. Understanding why people procrastinate even under intense stress requires moving beyond willpower and examining the deeper psychological forces at play—emotions, brain function, fear of failure, and self-regulation.

Procrastination isn’t laziness. It’s an emotional regulation problem disguised as a time management issue. When stress amplifies anxiety, shame, or fear of imperfection, the brain seeks immediate relief. And what offers faster relief than distraction? Scrolling, checking emails, or reorganizing your desk may feel unproductive, but they serve a critical psychological purpose: they reduce discomfort in the short term. Unfortunately, this temporary comfort comes at a long-term cost—increased stress, guilt, and performance decline.

The Emotional Brain vs. The Rational Brain

At the core of procrastination is a conflict between two systems in the mind: the limbic system (emotional brain) and the prefrontal cortex (rational brain). The limbic system governs emotions, impulses, and survival instincts. It craves instant gratification and avoids pain. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning, decision-making, and self-control, tries to guide behavior toward long-term goals.

Under normal conditions, these systems can cooperate. But under stress, the balance shifts. High cortisol levels impair the prefrontal cortex, weakening executive functions like focus, impulse control, and working memory. Meanwhile, the limbic system becomes hyperactive, making emotional reactions stronger and more immediate. This neurological imbalance explains why, when stressed, people are more likely to give in to urges—even if they know those choices are counterproductive.

“Procrastination is not about poor time management; it's about mood regulation. People delay tasks not because they don’t care, but because they want to escape negative emotions associated with the task.” — Dr. Piers Steel, author of *The Procrastination Equation*

Fear of Failure and Perfectionism

One of the most powerful psychological drivers of stress-related procrastination is the fear of failure. Paradoxically, high achievers are especially vulnerable. They set extremely high standards, and the thought of falling short triggers intense anxiety. To avoid confronting that possibility, they delay starting altogether.

Perfectionism creates a mental trap: if you can't do something perfectly, why start at all? This all-or-nothing thinking leads to paralysis. The task looms larger in the mind, becoming synonymous with judgment, identity, and self-worth. As deadlines approach, stress intensifies, but so does the urge to avoid—creating a feedback loop where stress fuels procrastination, and procrastination increases stress.

The Role of Task Aversion and Emotional Triggers

Not all tasks are equally likely to trigger procrastination. Certain characteristics make a task emotionally aversive:

- Boring or repetitive work – Lacks intrinsic motivation.

- Unclear instructions – Creates uncertainty and anxiety.

- High personal significance – Tied to identity or fear of judgment.

- Punitive consequences – Associated with past criticism or failure.

When a task combines several of these traits, it becomes emotionally charged. The brain perceives it not just as work, but as a threat. In response, it activates avoidance behaviors—not out of defiance, but as a protective mechanism. This is why students delay writing important papers, professionals put off difficult conversations, and creatives abandon projects they care deeply about.

Real Example: The Graduate Student’s Dilemma

Consider Maria, a PhD candidate under immense pressure to submit her dissertation. She’s fully aware of the deadline and the consequences of delay. Yet, instead of writing, she spends hours organizing references, checking grammar rules, or researching tangential topics. On the surface, she appears busy. In reality, she’s avoiding the core task: writing original content.

Maria isn’t lazy. She’s overwhelmed by the weight of expectations—from her advisor, her family, and herself. Every sentence feels like a test of her competence. The stress makes the task emotionally unbearable, so her brain redirects energy toward “safer” activities. Her procrastination is a form of emotional self-protection, not defiance.

The Stress-Procrastination Cycle

What makes stress-induced procrastination particularly destructive is its self-reinforcing nature. The cycle follows a predictable pattern:

- Stress arises due to a looming deadline, high stakes, or personal pressure.

- Anxiety builds around the task, especially if it’s perceived as threatening.

- Avoidance begins as the brain seeks relief through distraction.

- Guilt and shame follow, increasing stress levels further.

- Performance suffers due to rushed work or incomplete effort.

- Self-doubt grows, reinforcing the belief that future tasks will be equally painful.

This loop doesn’t just harm productivity—it erodes self-esteem. Over time, chronic procrastinators begin to see themselves as undisciplined or incapable, which only deepens the emotional burden of future tasks.

Breaking the Cycle: A Step-by-Step Approach

Escaping this cycle requires more than discipline. It demands emotional awareness and strategic intervention. Here’s a practical timeline to disrupt stress-driven procrastination:

- Pause and Name the Emotion (Day 1)

When you feel the urge to avoid, stop and ask: What am I feeling? Anxiety? Shame? Fear of judgment? Naming the emotion reduces its power. - Lower the Stakes (Day 2)

Break the task into micro-steps. Instead of “write report,” try “open document and write one sentence.” Reducing the threshold for starting lowers resistance. - Schedule Short Work Bursts (Days 3–5)

Use the Pomodoro technique: 25 minutes of focused work, followed by a 5-minute break. Knowing there’s a guaranteed pause reduces dread. - Reflect Without Judgment (End of Week)

Review progress without self-criticism. Focus on effort, not outcome. Ask: What helped me move forward? What triggered avoidance? - Build Self-Compassion (Ongoing)

Treat yourself as you would a friend in the same situation. Replace “I should’ve started earlier” with “It’s okay—I’m learning how to manage stress better.”

Strategies That Actually Work

Traditional advice like “just start” or “manage your time better” rarely helps someone stuck in emotional overwhelm. Effective strategies address the root cause: emotion regulation. Below are evidence-based approaches that target the psychology of procrastination.

1. Practice Self-Compassion

Research shows that people who treat themselves with kindness after procrastinating are less likely to repeat the behavior. Self-criticism increases shame, which fuels further avoidance. Self-compassion, on the other hand, creates psychological safety, making it easier to return to the task.

2. Reduce Task Ambiguity

Unclear goals increase anxiety. Break large projects into specific, actionable steps. Instead of “work on presentation,” define “create slide 1 with title and three bullet points.” Clarity reduces cognitive load and makes starting feel manageable.

3. Use Temptation Bundling

Pair a disliked task with something enjoyable. For example: “I’ll listen to my favorite podcast only while reviewing financial reports.” This leverages the brain’s reward system to make unpleasant tasks more appealing.

4. Change Your Environment

Distractions aren’t just external—they’re habitual. If you always check your phone when stressed, create physical barriers: use website blockers, leave your phone in another room, or work in a library. Environmental design reduces reliance on willpower.

| Strategy | How It Helps | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Compassion | Reduces shame and fear of failure | “Everyone struggles sometimes. This doesn’t mean I’m failing.” |

| Task Chunking | Lowers perceived difficulty | “Just draft the introduction” instead of “write the whole essay” |

| Implementation Intentions | Automates decision-making | “When I sit at my desk, I will open the document first.” |

| Environmental Control | Removes temptation | Work in a quiet space without Wi-Fi for social media |

Checklist: How to Respond When Stress Triggers Procrastination

- ☑ Acknowledge the stress without judgment

- ☑ Identify the specific emotion (e.g., fear, boredom, overwhelm)

- ☑ Break the task into the smallest possible step

- ☑ Set a timer for 5–10 minutes of low-pressure work

- ☑ Reward yourself immediately after completing the micro-task

- ☑ Reflect on what worked, not just what didn’t

- ☑ Schedule a review session, not a full work session, for the next day

FAQ

Isn’t procrastination just a lack of discipline?

No. While discipline plays a role, research consistently shows that procrastination is primarily an emotional regulation issue. People delay tasks not because they lack motivation, but because they’re trying to manage negative emotions like anxiety, fear of failure, or boredom.

Can stress ever help with productivity?

Yes, but only up to a point. The Yerkes-Dodson Law suggests that moderate stress enhances performance by increasing alertness. However, excessive stress impairs cognitive function and triggers avoidance behaviors, leading to procrastination. The key is finding the optimal level of arousal—too little causes apathy, too much causes shutdown.

How is procrastination different from strategic delay?

Strategic delay is intentional—a conscious choice to postpone action for better timing or more information. Procrastination is passive and involuntary, driven by avoidance rather than strategy. The former feels empowering; the latter feels draining.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Agency Over Action

Procrastination under stress is not a moral failing. It’s a predictable human response to emotional pressure. Recognizing this removes shame and opens the door to real change. By addressing the underlying emotions—fear, perfectionism, ambiguity—and applying targeted strategies, it’s possible to disrupt the cycle.

The goal isn’t to eliminate stress or never procrastinate again. That’s unrealistic. The goal is to build resilience—to shorten the duration of avoidance, reduce self-judgment, and return to action more quickly. Each time you choose to engage despite discomfort, you strengthen your capacity for self-regulation.

You don’t need more willpower. You need better emotional tools. Start small. Be kind. And remember: progress isn’t measured by perfection, but by persistence.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?