When winter storms blanket sidewalks and driveways in snow and ice, a familiar sight follows: people scattering white granules across slippery surfaces. That substance is usually salt — specifically rock salt or sodium chloride. But why do so many rely on this simple mineral to keep pathways safe? And more importantly, how does it actually work? The answer lies in basic chemistry, physics, and decades of municipal practice. Understanding the science behind salting sidewalks reveals not only how effective it can be but also its limitations and environmental trade-offs.

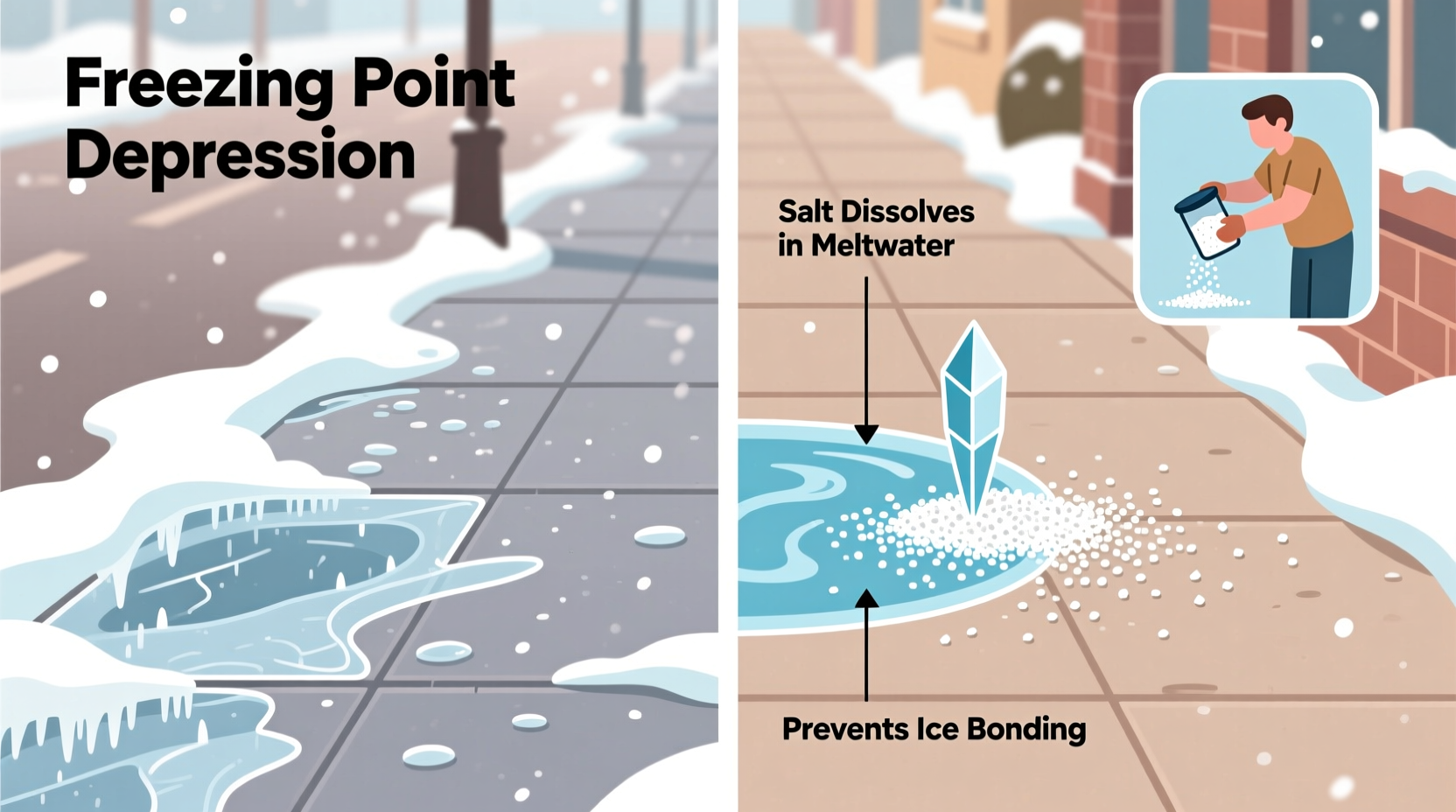

The Science Behind Freezing Point Depression

Salt doesn’t “melt” ice in the way heat does. Instead, it interferes with the freezing process through a phenomenon known as freezing point depression. Pure water freezes at 32°F (0°C). When salt is added to ice, it dissolves into the thin layer of liquid water always present on the surface of frozen surfaces. This creates a saline solution — brine — that has a lower freezing point than pure water.

For example, a 10% saltwater solution freezes at about 20°F (-6.7°C), while a 20% solution won’t freeze until around 2°F (-19°C). This means that even in subfreezing temperatures, salt can prevent melted snow from refreezing and help break the bond between ice and pavement.

The process begins when salt crystals come into contact with ice. They attract moisture and start forming brine. As this brine spreads, it penetrates deeper into cracks and under layers of ice, accelerating the melting process from below. Over time, the ice structure weakens and becomes slushy, making it easier to remove mechanically or simply wash away.

“Salt doesn’t generate heat — it enables existing thermal energy in the environment to work more effectively against ice.” — Dr. Alan Peterson, Environmental Chemist, University of Vermont

Types of Salts Used for De-Icing

Not all salts are created equal. While sodium chloride (rock salt) is the most common due to its low cost and availability, other de-icing compounds offer advantages in extreme cold or sensitive environments.

| Type of Salt | Effective Temperature Range | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) – Rock Salt | Down to 15–20°F (-9 to -6°C) | Inexpensive, widely available | Corrodes metal, harms vegetation, less effective in very cold temps |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Down to -20°F (-29°C) | Exothermic reaction (releases heat), works faster | More expensive, hygroscopic (can become wet), may irritate skin |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Down to 5°F (-15°C) | Less damaging to concrete and plants, eco-friendlier | Higher cost, can leave residue |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Down to 25°F (-4°C) | Biodegradable, safer for lawns | Limited effectiveness, higher price |

| Urea-Based Products | Down to 15°F (-9°C) | Non-corrosive, fertilizer component | Can contribute to nutrient pollution in waterways |

Homeowners often use blends labeled as “ice melt” mixtures, which combine two or more of these salts to balance performance, cost, and environmental impact. Municipalities typically opt for bulk rock salt for major roads but may use calcium chloride pre-treatments during severe storms.

Why Salt Works Better Than Sand or Other Alternatives

Some people use sand instead of salt, especially where traction is needed but temperatures are too low for salt to be effective. Sand increases friction, helping shoes and tires grip icy surfaces. However, unlike salt, sand does nothing to melt ice. It merely sits on top and can be messy, requiring cleanup once the snow clears.

Other alternatives like kitty litter, sawdust, or coffee grounds provide temporary traction but lack chemical action. They don’t alter the freezing point of water and can stain surfaces or attract pests. In contrast, salt actively changes the physical state of ice, turning solid hazards into manageable slush.

That said, salt isn’t always the best choice. On porous stone walkways, repeated salt exposure can lead to spalling — surface flaking caused by water expansion during freeze-thaw cycles. In environmentally sensitive areas, runoff containing chlorides can contaminate soil and groundwater.

Step-by-Step Guide to Effective Sidewalk Salting

Using salt properly maximizes safety while minimizing waste and environmental harm. Follow this timeline-based approach for optimal results:

- Monitor Weather Forecasts: Check predictions 24–48 hours ahead. If snow or freezing rain is expected, prepare your supplies.

- Pre-Treat Before Snowfall: Lightly apply salt to dry sidewalks just before precipitation starts. This creates a barrier that prevents ice adhesion.

- Shovel First, Then Salt: After snow stops, clear as much accumulation as possible. Salt works best on thin ice layers or damp surfaces, not deep snow.

- Apply Sparingly: Use about 12 ounces (roughly 3–4 handfuls) per 200 square feet. Over-application wastes resources and increases environmental damage without improving results.

- Allow Time for Action: Give salt 15–30 minutes to penetrate and begin melting. Reapply only if conditions worsen or new ice forms.

- Reassess Surface Conditions: Once slush forms, sweep or push it aside to prevent re-freezing. Consider using non-corrosive alternatives near gardens or delicate surfaces.

Timing matters. Applying salt during the day, when ambient temperatures are slightly higher, enhances its effectiveness. Avoid applying late at night unless necessary, as colder overnight temps reduce performance.

Environmental and Structural Concerns

While salt improves winter safety, its widespread use comes with consequences. Each year, millions of tons of road salt are applied across North America and Europe. Runoff carries chlorides into streams, lakes, and drinking water sources. Studies show elevated chloride levels in urban watersheds, threatening aquatic life and altering ecosystems.

High salt concentrations can kill freshwater organisms, disrupt reproduction cycles in fish, and promote algal blooms by changing nutrient balances. Soil near treated roads often shows reduced fertility, affecting plant growth and tree health.

Structurally, salt accelerates corrosion of vehicles, bridges, and rebar in concrete. It contributes to pothole formation by increasing the frequency of freeze-thaw cycles beneath pavement. Concrete driveways and older sidewalks may deteriorate faster with repeated salt exposure.

“We’ve seen a measurable increase in chloride contamination in suburban groundwater over the past two decades — largely tied to residential and municipal de-icing.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Hydrologist, Great Lakes Institute

Real-World Example: A Homeowner’s Winter Strategy

Consider Sarah, a homeowner in upstate New York, where winters bring frequent snow and ice. Last season, she experimented with different approaches. Early December, she used only rock salt after each storm. By January, she noticed brown patches forming along her sidewalk edge — signs of salt-damaged grass.

She switched tactics: shoveling promptly, using a magnesium chloride blend sparingly, and placing rubber mats on high-traffic steps. She began pre-salting with a handheld spreader calibrated to dispense small amounts evenly. She also started storing extra bags in a sealed container to keep them dry and effective.

The result? Fewer slip incidents, no new lawn damage, and nearly 40% less product used compared to the previous year. Her strategy combined timing, proper tools, and smarter material choices — proving that informed decisions make a tangible difference.

Checklist: Smart Salting Best Practices

- ✔️ Clear snow before applying salt

- ✔️ Use the right type of salt for current temperatures

- ✔️ Apply early — ideally before ice sets in

- ✔️ Measure application rates; avoid overuse

- ✔️ Keep pets and children away from freshly salted areas

- ✔️ Sweep up unused salt after thawing

- ✔️ Protect nearby plants with barriers or choose pet-safe, vegetation-friendly products

- ✔️ Store salt in airtight containers to prevent clumping

Frequently Asked Questions

Does salt stop snow from sticking?

Yes — when applied before snowfall, salt creates a brine layer that prevents snow and ice from bonding tightly to pavement. This makes shoveling or plowing far easier and reduces the chance of black ice forming later.

Is there a temperature when salt stops working?

Absolutely. Most common rock salt loses effectiveness below 15–20°F (-9 to -6°C). At such low temperatures, little liquid water exists on ice for salt to dissolve into, halting the brine-forming process. In extreme cold, calcium chloride or mechanical removal becomes necessary.

Are there eco-friendly alternatives to traditional salt?

Yes. Options include beet juice blends (used by some cities to enhance salt performance), cheese brine (a quirky but real alternative tested in Wisconsin), and commercially available organic de-icers made from corn or sugar derivatives. These reduce chloride load and can lower the effective freezing point further, though they may be more expensive or leave stains.

Conclusion: Balancing Safety, Science, and Sustainability

Sprinkling salt on snowy sidewalks isn’t just tradition — it’s grounded in scientific principles that make winter travel safer. By lowering the freezing point of water, salt transforms hazardous ice into manageable slush, preventing falls and accidents. But like any tool, it must be used wisely. Overuse harms the environment, damages infrastructure, and wastes resources.

The key is thoughtful application: choosing the right product for the conditions, timing it correctly, and combining it with physical removal methods like shoveling. With growing awareness of environmental impacts, innovations in de-icing technology continue to evolve — offering greener solutions without sacrificing safety.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?