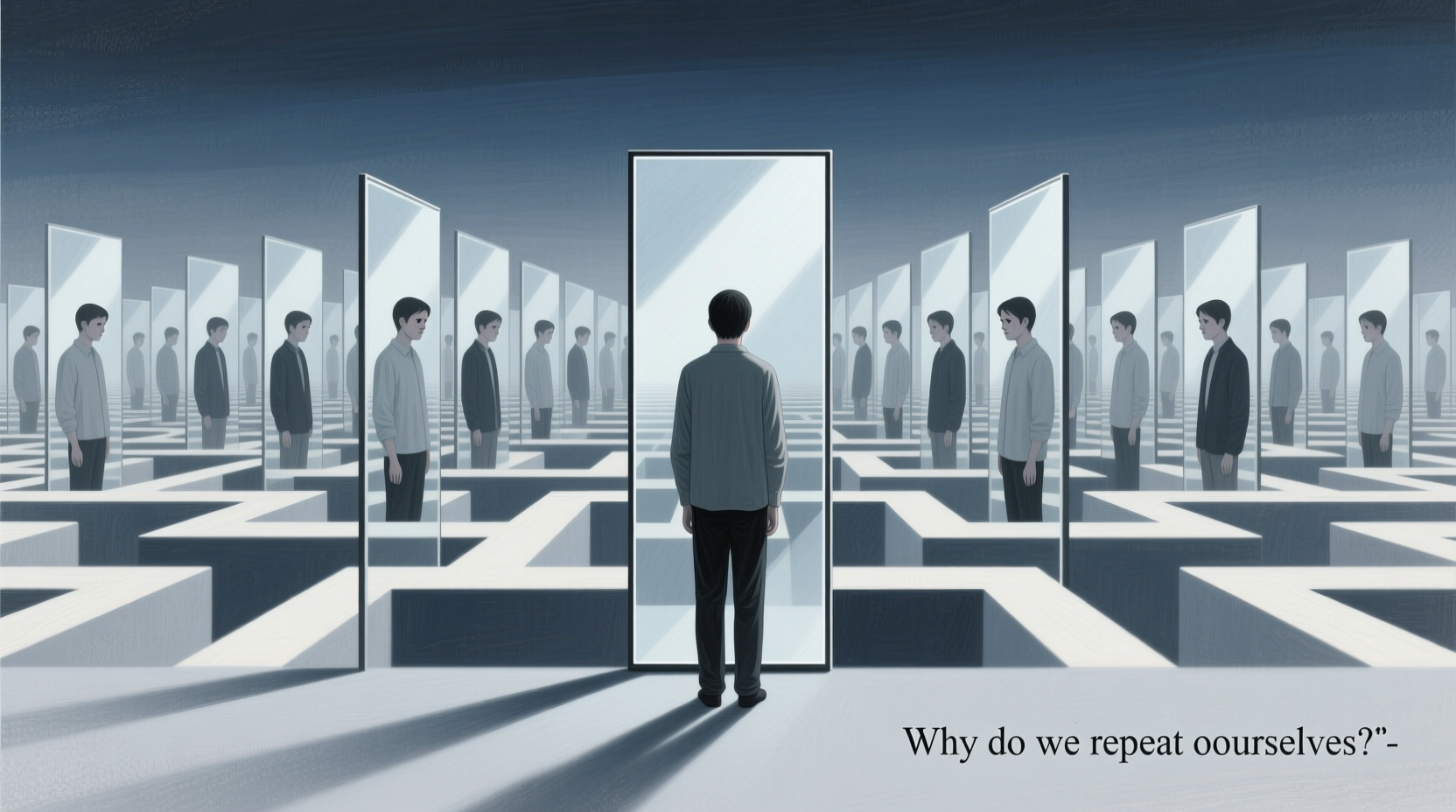

Repetition is a common feature of human communication, yet it often goes unnoticed—until it becomes noticeable. Whether in conversation, storytelling, or public speaking, people repeat words, phrases, or entire ideas for reasons that span from cognitive necessity to emotional emphasis. Understanding why repetition occurs can improve empathy, sharpen listening skills, and enhance both personal and professional interactions. It's not always a sign of forgetfulness or insecurity; sometimes, it’s a deliberate strategy rooted in psychology, culture, or neurology.

The Cognitive Function of Repetition

At its core, repetition supports memory retention and information processing. The brain relies on repeated exposure to solidify new knowledge. When someone repeats a point, they may be reinforcing their own understanding or ensuring the listener grasps the message. This is especially true in high-stakes conversations—such as medical consultations or safety briefings—where clarity is critical.

Neuroscience confirms that repetition strengthens neural pathways. Each time a concept is revisited, the brain encodes it more deeply. This explains why educators use repetition in teaching and why advertisers repeat slogans. In everyday speech, individuals may rephrase or echo statements to confirm comprehension, particularly when discussing complex topics.

Emotional and Psychological Drivers

Repetition isn’t solely about cognition; it often reflects emotional states. Anxiety, for example, frequently manifests as verbal repetition. A person worried about being misunderstood may say the same thing multiple times, seeking reassurance through confirmation. Similarly, individuals with obsessive-compulsive tendencies might repeat phrases as part of internal rituals.

In grief or trauma, repetition serves as a coping mechanism. Survivors recounting painful events may repeat details not because they expect new outcomes, but because retelling helps process emotions. Psychologist Dr. Bessel van der Kolk notes that trauma disrupts normal narrative flow, causing survivors to loop through key moments until integration occurs.

“Repetition in trauma narratives isn't redundancy—it's an attempt to make sense of what initially felt senseless.” — Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, Trauma Researcher

Cultural and Rhetorical Uses of Repetition

Across cultures, repetition holds symbolic power. In oral traditions—from African griots to Indigenous storytelling—repetition preserves accuracy and honors rhythm. Religious texts and rituals also rely on repeated phrases to instill reverence and communal identity. Think of mantras in meditation or call-and-response in sermons: these are not flaws in delivery but intentional tools for engagement and meaning-making.

Rhetorically, repetition is a cornerstone of persuasive speech. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. used anaphora—the repetition of words at the beginning of successive clauses—to build momentum and emotional resonance. “I have a dream” wasn’t said once; it was echoed to unify, inspire, and imprint the message into collective memory.

| Type of Repetition | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Anaphora | Create rhythm and emphasis | \"We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds...\" – Winston Churchill |

| Epistrophe | Highlight closure or urgency | \"...government of the people, by the people, for the people.\" – Abraham Lincoln |

| Rephrasing | Clarify complex ideas | Explaining a diagnosis in simpler terms after medical jargon |

| Insistent repetition | Express anxiety or demand attention | \"Did you hear me? I said we need to leave now.\" |

When Repetition Signals Underlying Conditions

While often functional, persistent repetition can indicate neurological or developmental conditions. Individuals with dementia may repeat questions because short-term memory is impaired. Autistic individuals might repeat phrases (echolalia) as a way to process language or self-regulate. Aphasia patients, recovering from stroke, often circle back to words as they rebuild linguistic capacity.

It’s crucial not to dismiss such repetition as mere annoyance. Responding with patience and context-awareness fosters dignity and connection. For caregivers, recognizing patterns helps distinguish between communicative intent and cognitive decline.

Mini Case Study: Supporting a Parent with Early-Stage Dementia

Sarah noticed her 72-year-old father kept asking when her sister was visiting—even minutes after she’d answered. At first, she grew frustrated, thinking he wasn’t listening. After consulting a neurologist, she learned his repetition stemmed from memory gaps, not defiance. She began using a whiteboard calendar and responded calmly each time: “She’s coming Saturday at 2 p.m., just like we talked about.” Over time, this consistency reduced his anxiety and her stress. The repetition didn’t stop, but their relationship improved because she reframed it—not as a flaw, but as a signal for support.

How to Respond Constructively to Repetitive Speech

Reacting to repetition with impatience can escalate tension or isolate the speaker. Instead, consider the underlying cause and adapt your response. Is the person anxious? Confused? Emphasizing a point? Your reaction should match the context.

- Listen fully before responding. Interrupting reinforces insecurity.

- Acknowledge the message with phrases like “I hear you” or “That’s important.”

- Clarify gently: “Just to make sure I understand, are you saying…?”

- Redirect if needed: “We’ve covered that—can we focus on the next step?”

- Use nonverbal cues: Nodding or maintaining eye contact shows engagement without verbal overlap.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is repeating oneself a sign of dementia?

Not always. Occasional repetition is normal, especially under stress. However, frequent, uncontrolled repetition—especially with no awareness—can be an early sign of cognitive decline. Consult a healthcare provider if it disrupts daily life.

Why do some people repeat questions right after asking them?

This can stem from uncertainty, hearing difficulties, or fear of not being heard. It may also reflect social anxiety—seeking validation through repetition. Active listening and clear responses usually reduce the cycle.

Can repetition be a manipulation tactic?

In rare cases, yes. Some individuals use insistent repetition to dominate conversations or wear down opposition. This differs from anxious or cognitive repetition, as it’s coupled with controlling behavior. Setting boundaries is key in such situations.

Action Checklist: Responding with Empathy

- Pause before reacting—ask yourself why the repetition might be happening.

- Validate the speaker’s feelings, even if the content is repeated.

- Use visual aids (calendars, notes) when memory issues are suspected.

- Stay calm and consistent in tone.

- Seek professional insight if repetition increases suddenly or causes distress.

Conclusion: Reframing Repetition as Communication, Not Noise

Repetition is rarely meaningless. Whether it’s a teacher reinforcing a lesson, a loved one seeking reassurance, or a leader rallying a movement, repetition carries intent. By understanding its roots—in memory, emotion, culture, and cognition—we become better listeners and more compassionate communicators. Instead of tuning out, we can lean in, ask thoughtful questions, and respond with patience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?