It’s a common moment: you reach for your holiday string lights, wrap them around the mantel, and notice one strand feels noticeably warm—almost hot—while another nearby remains cool to the touch. You pause. Is it malfunctioning? Is it about to fail—or worse, pose a fire hazard? This tactile discrepancy unsettles many consumers, especially as LED lighting becomes ubiquitous in homes, offices, and outdoor displays. The truth isn’t binary: warmth alone doesn’t equal danger, nor does coolness guarantee safety. What matters is *why* the heat occurs, *how much* is generated, *where* it’s concentrated, and *how well* the fixture manages it. This article cuts through marketing myths and thermal oversimplifications to give you grounded, engineer-informed clarity—so you can evaluate LED sets with confidence, not confusion.

How LEDs Generate Heat (and Why It’s Not Just About Efficiency)

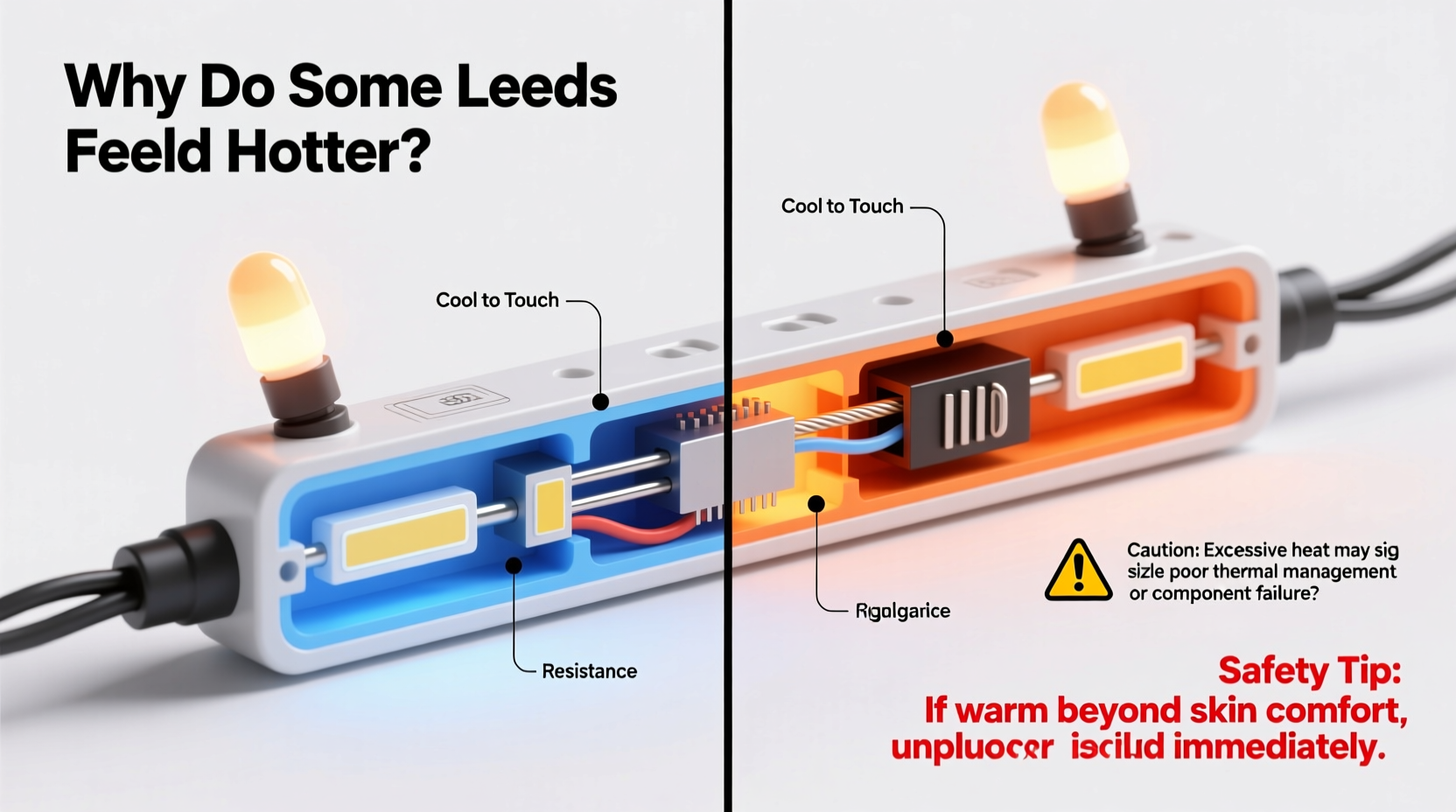

Contrary to popular belief, LEDs don’t produce light without heat. While they convert far more electrical energy into visible light than incandescent bulbs (which waste ~90% as infrared radiation), modern white LEDs still operate at only 40–55% wall-plug efficiency under real-world conditions. The remaining 45–60% becomes heat—but crucially, *not* as radiant infrared like old bulbs. Instead, it’s conducted heat generated at the semiconductor junction—the tiny chip where electrons recombine to emit photons. That heat must travel through layers of epoxy, solder, circuit board, housing, and air before dissipating. Any bottleneck along that path raises the surface temperature you feel.

What determines whether that heat reaches your fingertips? Three interdependent factors:

- Driver design: Cheap constant-voltage drivers often overdrive LEDs or lack thermal regulation, causing excess current and localized heating.

- Thermal path integrity: High-quality sets use metal-core printed circuit boards (MCPCBs), aluminum housings, or copper traces to move heat away from the chip. Budget versions rely on FR-4 fiberglass boards and plastic casings—poor conductors that trap heat.

- Ambient conditions and installation: Enclosing LEDs in tight spaces (e.g., behind curtains, inside glass globes, or bundled under insulation) impedes airflow and causes temperatures to climb—even if the set itself is well-designed.

So when one LED string feels warm and another doesn’t, it’s rarely about “good vs. bad” LEDs—it’s about the full thermal ecosystem engineered around them.

Surface Temperature Ranges: What’s Normal, What’s Not

Surface temperature isn’t arbitrary—it’s measurable, regulated, and context-dependent. Under UL 8750 (the U.S. safety standard for LED equipment), accessible surfaces of Class II (double-insulated) lighting must stay below 70°C (158°F) during normal operation. For Class I (grounded) devices, limits are stricter: 60°C (140°F) for metal and 85°C (185°F) for nonmetallic parts. But these are *maximum allowable* thresholds—not comfort targets. In practice, safe, high-quality LED strings typically register 30–45°C (86–113°F) at the bulb housing after 30 minutes of continuous use—warm but comfortably touchable. Budget or poorly ventilated sets may hit 55–65°C (131–149°F)—noticeably hot, potentially uncomfortable to hold, but still within code if properly rated.

When Warmth Becomes a Red Flag: 5 Warning Signs

Not all warmth warrants alarm—but certain patterns signal underlying issues demanding attention. These aren’t theoretical risks; they reflect documented failure modes observed in field testing by lighting engineers and fire investigators.

- Localized hot spots: One bulb or section feels significantly hotter than adjacent ones—especially if accompanied by flickering or dimming. Suggests failing solder joint, cracked die, or driver imbalance.

- Rapid temperature rise: The set goes from cool to too-hot-to-touch in under 10 minutes. Points to inadequate thermal design or counterfeit components operating beyond spec.

- Burning odor or discoloration: A faint acrid smell, yellowing plastic near LEDs, or charring on wires means insulation is degrading—a precursor to short circuits.

- Warmth persists after power-off: If the housing stays hot for more than 2–3 minutes post-shutdown, thermal mass is excessive or dissipation is blocked (e.g., LEDs buried in foam or fabric).

- Heat coincides with voltage irregularities: Using the set with an incompatible dimmer, extension cord >50 ft, or shared circuit with high-draw appliances increases resistive heating in wiring.

Crucially, UL certification doesn’t eliminate these risks—it verifies compliance *under lab conditions*. Real-world misuse erodes safety margins quickly.

Real-World Case Study: The Patio String Light Incident

In late 2022, a homeowner in Portland, Oregon installed two identical-looking 100-light LED string sets—one purchased from a major online retailer ($12.99), the other from a local lighting specialty store ($34.95). Both were labeled “UL Listed” and marketed for outdoor use. They ran them side-by-side on a covered patio pergola for holiday season. After three weeks, the budget set developed a distinct hot spot near its inline transformer—reaching 72°C (162°F) per IR thermometer. The premium set remained at 41°C (106°F) across all segments.

Investigation revealed key differences: the budget set used a plastic-housed, non-thermally-regulated driver with no heatsinking; its PCB was standard FR-4 with no copper pour. The premium version employed an aluminum-backed PCB, a thermally adaptive driver that reduced current above 50°C, and a metal-alloy transformer housing acting as a passive heatsink. When both sets were subjected to 40°C ambient temps and 85% humidity (simulating Pacific Northwest summer nights), the budget set’s driver failed catastrophically after 47 hours—tripping the GFCI. The premium set operated continuously for 1,200+ hours without deviation.

This wasn’t a fluke—it exemplifies how thermal design choices, invisible to the consumer, directly determine longevity and safety under stress.

Expert Insight: What Engineers Prioritize

“Consumers fixate on lumen output and color temperature—but thermal resistance (°C/W) is the silent determinant of reliability. A 1°C rise in junction temperature cuts LED lifespan by roughly 1% for every 10,000 hours. That’s why we specify MCPCBs, derate drivers by 20% at 40°C ambient, and validate thermal performance at 110% load—not just nominal. ‘Warm to touch’ isn’t the problem; uncontrolled junction temperature is.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Principal Thermal Engineer, Lumina Labs

Do’s and Don’ts: A Practical Safety Checklist

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Purchasing | Verify UL/ETL listing *and* check for “wet location” or “damp location” rating if using outdoors | Assume “LED” or “energy efficient” implies safety—ignore certifications |

| Installation | Allow 2–3 inches of space between strands and combustibles (curtains, dried foliage, wood) | Bundle tightly with zip ties or coil excess length into insulated containers |

| Operation | Use a timer or smart plug to limit daily runtime to ≤12 hours; avoid overnight use on flammable surfaces | Plug multiple high-wattage LED sets into one outlet strip without checking total load (max 1,500W per 15A circuit) |

| Maintenance | Inspect annually for cracked housings, exposed wires, or brittle insulation—replace immediately if found | Clean with solvents or abrasive cloths; use only dry microfiber or slightly damp cloth |

| Storage | Coil loosely in ventilated container; store in climate-controlled space <25°C (77°F) | Leave strung on trees or wrapped in plastic bags where moisture can condense |

Step-by-Step: How to Audit Your Existing LED Sets

Before your next holiday season—or any extended display—perform this five-minute thermal audit. No tools required beyond observation and touch:

- Power on: Turn on the set for exactly 30 minutes in its intended location (don’t test while coiled or in storage).

- Scan for variance: Run fingers gently along each bulb housing and the driver/transformer. Note any areas significantly warmer than others.

- Check surroundings: Are bulbs touching fabric, paper, or wood? Is airflow restricted? Is the driver sitting on carpet or tucked behind furniture?

- Smell & inspect: Sniff near the driver and first 3 bulbs. Look for discoloration, bubbling plastic, or frayed wire ends.

- Decide: If all sections feel uniformly warm (<45°C subjective), no odor, and proper spacing exists—continue use. If hot spots, odor, or damage appear, retire the set. Do not attempt repair.

This isn’t paranoia—it’s preventive maintenance rooted in decades of fire incident data. According to the NFPA’s 2023 report, 41% of decorative lighting fires involved equipment older than 10 years, and 68% occurred in sets showing prior signs of overheating (discoloration, intermittent function) ignored by owners.

FAQ: Addressing Common Concerns

Can LED lights cause fires?

Yes—but rarely due to the LED chips themselves. Fire risk stems from component failure in supporting electronics: overloaded drivers, degraded insulation on cheap wiring, or poor connections causing arcing. UL-listed, properly installed LED sets have a fire incidence rate under 0.002% per year—lower than incandescent counterparts. Risk escalates sharply with uncertified products, physical damage, or misuse (e.g., indoor-rated sets used outdoors).

Why do “cool white” LEDs sometimes feel warmer than “warm white” ones?

Color temperature (measured in Kelvin) describes light appearance—not heat output. A 5000K “cool white” LED may feel warmer because it’s often driven at higher current to achieve brightness targets, or because cheaper cool-white phosphor blends generate more heat at the junction. The correlation is coincidental, not causal.

Does dimming reduce heat significantly?

Yes—if using a compatible PWM (pulse-width modulation) dimmer designed for LEDs. Dimming to 50% brightness typically reduces heat output by ~40%, as power draw drops non-linearly. However, phase-cut dimmers (designed for incandescents) can cause driver instability and *increase* localized heating in some LED sets—so always verify dimmer compatibility.

Conclusion: Warmth Is Data—Not Destiny

That subtle warmth on an LED housing isn’t a warning siren—it’s thermal data waiting to be interpreted. It reflects material choices, engineering rigor, and usage context. Recognizing the difference between benign conduction and hazardous accumulation empowers you to make informed decisions: choosing certified products, installing with airflow in mind, retiring aging sets proactively, and trusting your senses—not fear—as your first diagnostic tool. Lighting should enhance life, not distract with doubt. When you understand *why* warmth occurs—and how to read its signals—you transform uncertainty into quiet confidence. Your next string of lights won’t just glow; it will perform reliably, beautifully, and safely, season after season.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?