Every fall, millions of people willingly line up to be terrified in dimly lit corridors filled with jump scares, eerie sounds, and masked figures lunging from shadows. Haunted houses are a cultural phenomenon, drawing thrill-seekers and casual visitors alike. But why would anyone choose fear as entertainment? The answer lies deep within the human brain—a complex network of chemicals, neural pathways, and evolutionary instincts that turn panic into pleasure under the right conditions.

The enjoyment of fear is not irrational. In fact, it’s deeply rooted in biology. When we experience controlled fear—such as in a haunted attraction—our brains engage in a paradoxical dance between danger and safety. This unique emotional cocktail can produce euphoria, social bonding, and even personal empowerment. Understanding this requires exploring neurochemistry, psychology, and the subtle cues our minds use to distinguish real threats from simulated ones.

The Brain’s Fear Response: A Survival Mechanism Turned Entertainment

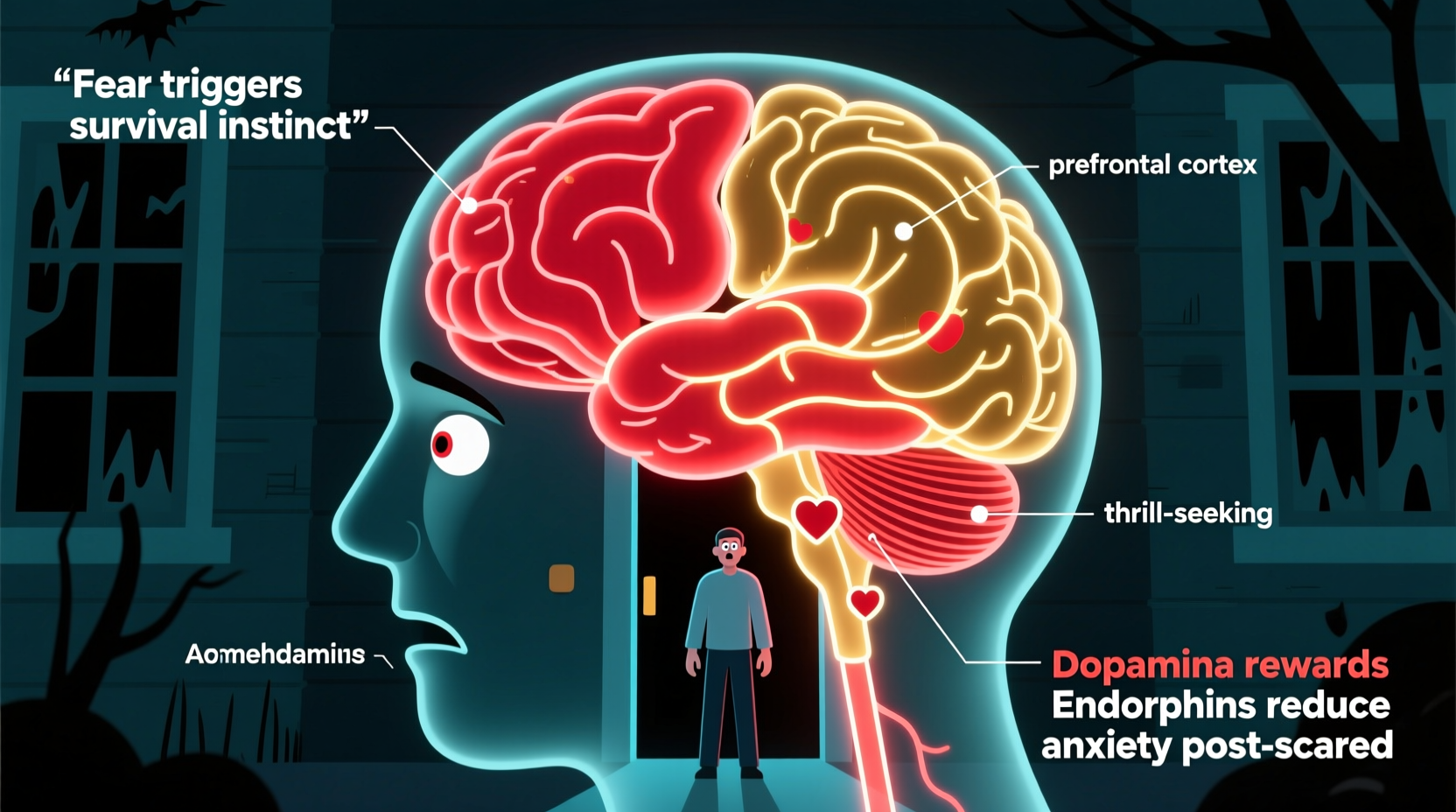

Fear is one of the oldest and most essential emotions in the animal kingdom. At its core, it’s a survival mechanism designed to protect us from harm. When the brain detects a potential threat, the amygdala—an almond-shaped structure deep within the temporal lobe—triggers a cascade of physiological responses. This is commonly known as the “fight-or-flight” response.

During this process, the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system, which signals the adrenal glands to release adrenaline (epinephrine) and cortisol. Heart rate increases, breathing quickens, muscles tense, and blood flow shifts to vital organs. These changes prepare the body to either confront or escape danger.

What makes haunted houses fascinating is that they simulate this entire response without actual danger. The brain recognizes the environment as threatening based on sensory input—sudden noises, dark spaces, unpredictable movements—but higher cognitive functions, particularly the prefrontal cortex, override the alarm by reminding us: This isn’t real.

“Fear itself isn’t unpleasant—it’s the context that determines whether we perceive it as terrifying or thrilling.” — Dr. Joseph LeDoux, Neuroscientist and Author of *Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety*

This cognitive awareness creates a safe frame around the experience, allowing the body to enjoy the rush of arousal without the consequences of true peril. It’s similar to riding a roller coaster: the sensation of falling triggers primal fear circuits, but the conscious mind knows you’re strapped in securely.

Dopamine and the Pleasure of Controlled Fear

One key reason people enjoy haunted houses lies in the brain’s reward system. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement learning, plays a crucial role in the thrill of fear.

Studies using functional MRI scans have shown that individuals who seek out high-arousal experiences—like horror films or extreme sports—often have more active dopamine systems. When these people encounter a scare in a controlled setting, their brains release dopamine not just after surviving the threat, but often during the anticipation of it.

In essence, the brain rewards successful navigation of perceived danger. Surviving a zombie ambush in a haunted house may not carry real stakes, but the mind still registers it as a minor victory. That sense of mastery triggers dopamine release, reinforcing the behavior and making the person more likely to seek similar experiences again.

This phenomenon explains why some people become “horror junkies”—returning year after year to increasingly intense attractions. For them, the dopamine payoff outweighs any discomfort, turning fear into a form of recreation.

The Role of Context and Safety Cues

Not everyone enjoys being scared—even in safe environments. The difference often comes down to how the brain interprets context.

Safety cues are environmental signals that tell the brain an experience is non-threatening despite surface-level fear triggers. In a haunted house, these include knowing the location, having paid admission, seeing other smiling guests exit, or noticing staff in visible uniforms. These subtle inputs allow the brain to maintain a dual awareness: I am scared, and I am safe.

Without these cues, the same stimuli could trigger trauma or anxiety. For example, if someone were suddenly grabbed in a dark alley by a stranger in a mask, the brain would interpret it as a genuine threat, activating full-blown fear with no pleasurable component.

Psychologists refer to this as “the paradox of negative emotion,” where aversive feelings like fear or sadness can be enjoyable when experienced in a safe, voluntary, and socially shared context. Theater, music, and literature rely on this principle—think of crying during a moving film. The emotion is real, but the framing makes it meaningful rather than distressing.

| Experience | Perceived Threat Level | Emotional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Jump-scare in a haunted house | Low (contextually safe) | Excitement, laughter, arousal |

| Unexpected loud noise at night at home | High (uncertain context) | Anxiety, stress, vigilance |

| Watching a horror movie with friends | Low to moderate | Engagement, bonding, thrill |

| Being followed in a parking garage | High (real-world risk) | Fear, panic, trauma potential |

Social Bonding Through Shared Fear

Another compelling reason people enjoy haunted houses is the powerful social effect of shared fear. When groups go through frightening experiences together, they often report feeling closer afterward. This phenomenon is linked to increased oxytocin production and synchronized physiological responses.

Research has shown that when people face mild stressors in group settings—such as watching a scary movie or navigating a haunted maze—their heart rates tend to synchronize. This alignment fosters empathy, trust, and connection. Screaming together, grabbing each other’s arms, or laughing nervously after a scare strengthens social bonds in ways few other activities can match.

Haunted houses are inherently social events. They’re rarely visited alone, and the shared vulnerability breaks down social barriers. In a world where digital interactions dominate, this kind of visceral, embodied experience offers rare opportunities for authentic human connection.

“We don’t just bond over joy—we bond over shared intensity. Fear, when mutual and contained, can be one of the fastest routes to closeness.” — Dr. Brooke Feeney, Social Psychologist and Expert on Close Relationships

Mini Case Study: The Halloween Group Trip

Consider a group of five college friends—two horror fans, two neutral, and one self-proclaimed “scaredy-cat”—who decide to visit a popular haunted attraction. Before entering, the anxious member hesitates, but peer encouragement and repeated reassurances (“It’s all actors!” “We’ll stay together!”) tip the balance.

Inside, the group clings to each other through narrow passages and surprise encounters. One friend screams so loudly she starts laughing mid-panic. Another grabs the arm of the hesitant visitor, creating a moment of physical connection that eases her fear. By the end, the previously reluctant participant admits, “I was terrified, but I’ve never laughed so hard with you guys.”

In the weeks that follow, the group references inside jokes from the experience, strengthening their friendship. What began as a test of courage became a memorable bonding event—proof that shared fear, when framed correctly, can be transformative.

Individual Differences: Who Enjoys Fear and Why?

Not everyone finds haunted houses enjoyable. Personality traits, past experiences, and neurochemical makeup all influence how we respond to simulated fear.

One well-established model is the **sensation-seeking** personality type, identified by psychologist Marvin Zuckerman. High sensation seekers crave novel, intense, and complex experiences. They’re drawn to adventure, risk, and emotional arousal—and they tend to enjoy haunted attractions far more than low sensation seekers.

Other factors include:

- Anxiety sensitivity: People who are highly sensitive to bodily sensations of anxiety (e.g., rapid heartbeat) are more likely to interpret arousal as dangerous, making fear experiences unpleasant.

- Previous trauma: Those with PTSD or traumatic histories may find simulated fear triggering, even when rationally aware of safety.

- Cultural background: Attitudes toward fear and horror vary across cultures, influencing what is considered entertaining versus disturbing.

Interestingly, some people grow into enjoying fear. A child terrified of ghosts might, as an adult, relish a well-crafted haunted house. This shift often reflects greater cognitive control, emotional regulation, and understanding of illusion versus reality.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Maximize Enjoyment at a Haunted House

- Choose the right venue: Research reviews and intensity ratings. Look for age recommendations and scare level indicators.

- Go with trusted companions: Shared fear is more enjoyable with people you feel safe with.

- Set expectations: Talk beforehand about boundaries—agree on hand signals or words to slow down or exit if needed.

- Breathe consciously: During intense moments, focus on slow, deep breaths to regulate your nervous system.

- Debrief afterward: Discuss the experience over food or drinks. Laughing about scares helps process the arousal and reinforces positive memories.

FAQ

Can enjoying fear be addictive?

While not clinically addictive, the dopamine-driven thrill of fear can become habit-forming for some individuals. Regular exposure to controlled fear—like visiting haunted houses every season—can reinforce the desire for similar highs, much like exercise or spicy food. However, it remains a healthy behavioral preference unless it interferes with daily functioning or leads to risky real-world choices.

Why do children react so strongly to haunted houses?

Children’s brains are still developing the ability to distinguish fantasy from reality. Their prefrontal cortex, responsible for rational evaluation, isn’t fully mature, so a monster in a mask may register as genuinely threatening. Additionally, younger kids have less control over their environment, amplifying feelings of helplessness. Experts recommend waiting until ages 10–12 before introducing haunted attractions, depending on the child’s temperament.

Are there mental health benefits to experiencing fear in a safe setting?

Yes. Controlled fear exposure can build emotional resilience, improve stress tolerance, and boost confidence. Successfully navigating a frightening situation—even a fake one—can enhance self-efficacy. Some therapists even use guided exposure to fear-inducing stimuli as part of treatment for anxiety disorders, helping patients reframe their relationship with arousal and uncertainty.

Conclusion: Embracing the Thrill with Awareness

The appeal of haunted houses isn’t about masochism or recklessness—it’s about the brain’s remarkable ability to transform fear into fun. Through precise neurochemical signaling, cognitive framing, and social dynamics, humans have turned one of our most primal emotions into a seasonal celebration.

Understanding the science behind this phenomenon doesn’t diminish the magic; it enhances it. Knowing how dopamine surges, how safety cues modulate fear, and how shared scares deepen relationships allows us to engage more mindfully with these experiences.

Whether you're a seasoned haunt veteran or someone curious about why others scream with delight, the message is clear: fear, when chosen and contained, can be a gateway to excitement, connection, and growth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?