For many, cilantro is a vibrant, citrusy herb that elevates salsas, curries, and salads. For others, it’s an olfactory nightmare—described as soapy, musty, or even reminiscent of body odor. This sharp divide in perception isn’t just picky eating; it’s rooted deeply in human biology. The reason some people can't stand the smell of cilantro lies in their DNA. What one person experiences as fresh and fragrant, another interprets as repulsive—all due to a few variations in genetic code.

This phenomenon offers a fascinating window into how genetics shape sensory experience, food preferences, and even cultural cuisines. Understanding the science behind cilantro aversion reveals more than just taste quirks—it highlights the personalized nature of perception itself.

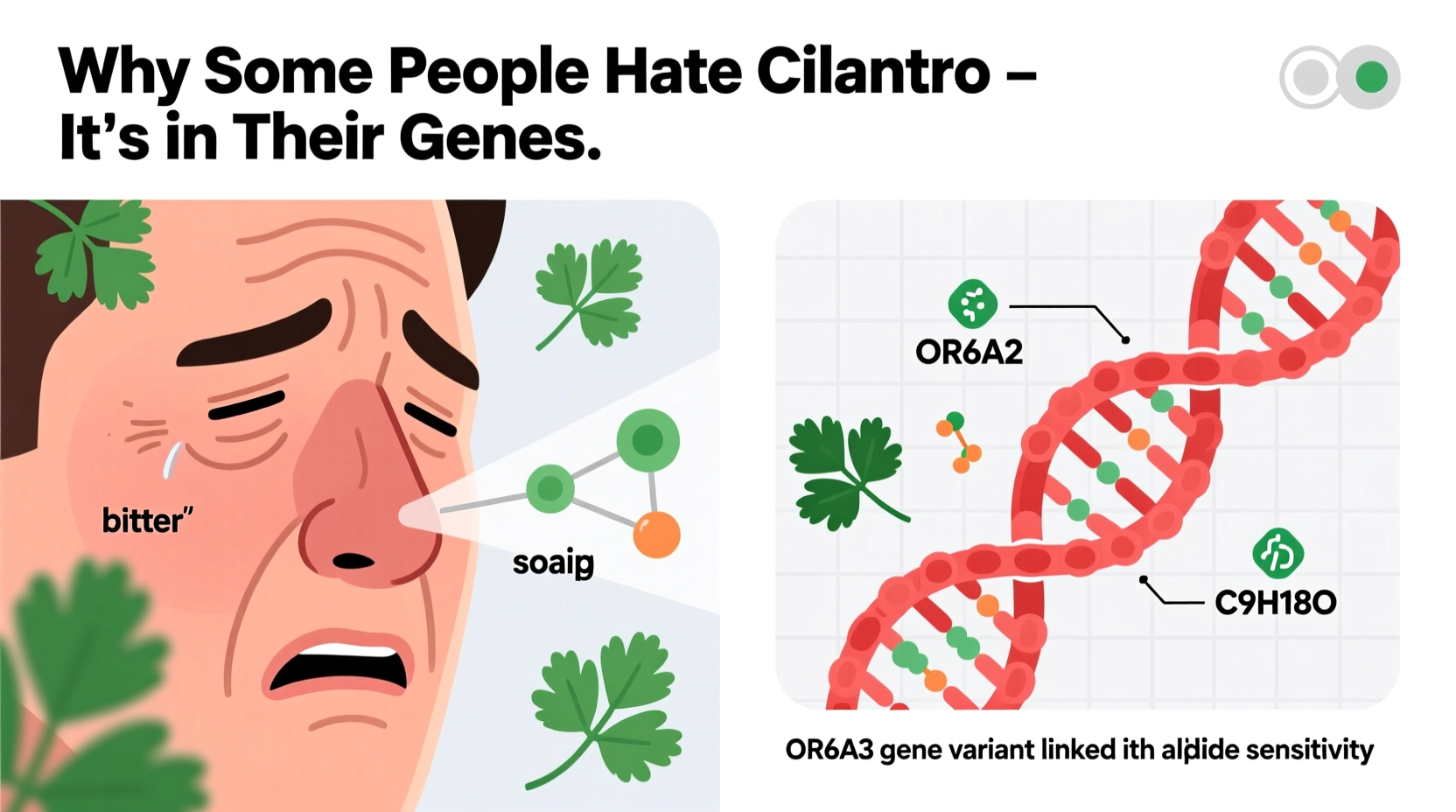

The Chemical Culprit: Aldehyde Compounds

The source of cilantro’s controversial aroma lies in a group of chemical compounds called aldehydes. These organic molecules are naturally present in cilantro leaves and are responsible for its distinctive scent. However, aldehydes are not unique to herbs. They’re also found in soaps, lotions, and even some insect secretions.

Specifically, two aldehyde compounds—decanal and (E)-2-decenal—are most associated with cilantro’s polarizing smell. To individuals with certain genetic variants, these compounds trigger olfactory receptors that interpret them similarly to the chemicals used in soap manufacturing. This cross-perception is why some people insist cilantro “tastes like shampoo.”

Interestingly, when cilantro is chopped or crushed, it releases more of these volatile aldehydes, intensifying the scent. Cooking can alter their structure slightly, which is why some who dislike raw cilantro may tolerate it when cooked.

Genetic Basis of Cilantro Aversion

The key to understanding cilantro hatred lies in the OR6A2 gene—a segment of DNA that codes for an olfactory receptor in the nose. This receptor is highly sensitive to aldehyde compounds. Research published in the journal Molecular Medicine found that individuals with a specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs72921001, are far more likely to detect the soapy notes in cilantro.

In a large-scale study analyzing over 25,000 participants, scientists discovered that those carrying two copies of the “sensitive” variant (one from each parent) were three times more likely to report disliking cilantro compared to those with no copies. The variation doesn’t make someone “wrong” about the taste—it simply means their nose detects different aspects of the same chemical profile.

It’s important to note that this gene doesn’t act alone. Other genes related to bitter taste perception—such as TAS2R38—may also play a supporting role, especially in how cilantro’s aftertaste is experienced. But OR6A2 remains the primary genetic marker linked to the soapy perception.

Global Distribution of Cilantro Sensitivity

Cilantro aversion isn’t evenly distributed across populations. Genetic studies show significant variation by ancestry:

| Population Group | Prevalence of Cilantro Aversion |

|---|---|

| East Asian | ~21% |

| European | ~17% |

| Hispanic | ~12% |

| Middle Eastern | ~7% |

| South Asian | ~3% |

The higher prevalence among East Asians and Europeans correlates with greater frequency of the OR6A2 sensitivity allele in those populations. In contrast, regions where cilantro has been a dietary staple for generations—like South Asia and parts of Latin America—show lower rates of aversion, possibly due to both genetic adaptation and cultural exposure from an early age.

“Cilantro aversion is one of the clearest examples we have of how a single gene can influence food preference. It shows that taste isn’t universal—it’s personal.” — Dr. Sarah Tishkoff, Professor of Genetics and Biology, University of Pennsylvania

Can You Retrain Your Brain to Like Cilantro?

While genetics set the foundation, experience and environment shape how we respond. Many people who once hated cilantro report growing to enjoy it over time. This shift isn’t due to genetic change—but rather to neural adaptation in the brain’s olfactory processing centers.

The brain learns to associate flavors with context. If someone repeatedly consumes cilantro in positive settings—say, in delicious Thai soups or fresh Mexican guacamole—the emotional reward can override initial disgust. Over time, the brain begins to link the smell not with soap, but with pleasure, flavor, and satiety.

This process mirrors how acquired tastes develop for coffee, blue cheese, or beer. Discomfort fades as familiarity grows.

Step-by-Step Guide to Developing a Taste for Cilantro

- Start small: Add a single leaf or pinch of chopped cilantro to familiar dishes like rice or scrambled eggs.

- Cook it lightly: Heat alters aldehyde compounds. Try sautéing or simmering cilantro in soups or stews.

- Pair with strong flavors: Combine with garlic, lime, chili, or coconut milk to balance the aroma.

- Use stems sparingly: The stems contain fewer volatile oils and are less pungent than leaves.

- Wait and repeat: Taste again after a week. Consistency over weeks can rewire associations.

Real-Life Example: Maria’s Journey from Hatred to Acceptance

Maria, a 34-year-old teacher from Chicago, avoided Mexican food for years because of her intense aversion to cilantro. “I’d order tacos and immediately pick out every green fleck,” she recalls. “My friends thought I was crazy, but it really smelled like dish soap to me.”

After moving to Austin and attending frequent taco nights, she decided to challenge her bias. She started by asking for “just a tiny bit” on her tacos, then focused on enjoying the other flavors—spicy salsa, tender carne asada. Over six months, she gradually increased the amount.

“One day, I realized I didn’t even notice it anymore,” she says. “Now I add it to my black bean soup at home. I wouldn’t say I crave it, but I don’t run from it either.”

Maria’s experience reflects neuroplasticity in action. Her genetic sensitivity didn’t change—but her brain’s interpretation of the signal did.

Do’s and Don’ts When Serving Cilantro

Given how divisive cilantro can be, consider your audience when preparing meals. Here’s a practical guide:

| Action | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Do: Ask guests about preferences | Especially in diverse groups, a quick check avoids discomfort. |

| Don’t: Assume everyone likes it | About 1 in 5 people have a strong negative reaction. |

| Do: Offer it on the side | Let individuals control their exposure. |

| Don’t: Dismiss complaints as “picky eating” | The aversion is biologically real, not imagined. |

| Do: Use alternatives like parsley or culantro | Parsley offers freshness without aldehydes; culantro (a relative) has a stronger but different profile. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is cilantro aversion a sign of a medical condition?

No. Disliking cilantro due to genetics is not a disorder. It’s a normal variation in sensory perception, similar to differences in hearing range or color vision. Unless accompanied by broader smell loss (anosmia) or neurological symptoms, it’s considered benign.

Can children outgrow cilantro dislike?

Some do. While genetic sensitivity persists, repeated exposure during childhood can lead to acceptance. Parents are advised not to force-feed cilantro but to offer it alongside enjoyable foods, allowing natural acclimation.

Are there any health risks to avoiding cilantro?

None. Though cilantro contains antioxidants and mild antimicrobial properties, it’s not nutritionally essential. People who avoid it can obtain similar benefits from other herbs like parsley, basil, or mint.

Broader Implications: Genetics and Food Preferences

The cilantro case is part of a larger trend in nutritional genomics—understanding how DNA influences diet. Scientists now recognize that taste and smell are polygenic traits, influenced by dozens of genes. Beyond cilantro, variations affect how we perceive bitterness (in broccoli or coffee), sweetness, umami, and even fat texture.

This knowledge is shaping personalized nutrition. In the future, genetic testing could help tailor dietary recommendations—not just for health conditions, but for palatability. Imagine a meal plan designed not only to lower cholesterol but also to align with your innate flavor preferences.

Moreover, recognizing genetic diversity in taste promotes empathy in culinary spaces. Instead of labeling someone a “picky eater,” we might begin to see them as genetically wired differently—a valid perspective in a world of varied sensory experiences.

Conclusion: Embracing Sensory Diversity

The divide over cilantro is more than a dinner table debate—it’s a testament to human diversity. Our genes shape not just our appearance, but how we experience the world through scent and taste. What seems delicious to one person may be repulsive to another, and both reactions are equally valid.

Understanding the genetics behind scent aversion fosters compassion in how we share food, design menus, and raise children. It reminds us that flavor is not objective—it’s a deeply personal intersection of biology and culture.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?